Jerry Avorn, M.D. Co-Founder & Special Adviser, NaRCAD Tags: Evidence Based Medicine, Jerry Avorn Following the astonishing debut of AI applications like ChatGPT a year ago, “knowledge workers” (that’s us) have been forced to ponder how much of what we do could be replaced by a very smart set of computer programs. Such applications can already pass medical licensing exams better than many graduates and have gotten remarkably good at reading X-rays and pathology specimens. How soon will AI systems become adept at reviewing the clinical literature and preparing concise, user-friendly summaries, complete with prescribing recommendations? Not yet, but likely before long.  Try it yourself at home: log onto OpenAI.com (it’s free) and ask ChatGPT for advice about medications for diabetes or hypertension or HIV or anything else. Just be careful about its “hallucinations” – the fact that sometimes AI just makes up wrong stuff. (I prefer the term “confabulation,” also used to describe this well-known phenomenon.) That can be whimsical if you’re a N.Y. Times reporter and ChatGPT advises you to leave your spouse, and it can be very problematic if you’re a lawyer who relies on case law that ChatGPT simply fabricated. (Both actually happened.) But it can be lethal if it involves incorrect clinical recommendations. Yet that said, AI is getting smarter every day. If programmed well in the coming years, large language models like ChatGPT or its growing number of competitors could eventually also learn how to gauge prescribers’ current knowledge, attitudes, and practices, and then ask just the right questions to find out why they’re doing what they’re doing, what their concerns are, and what it would take to get them to change.  Once things mature a bit further, will large health care systems interested in academic detailing and in cost-cutting simply replace humans with AI-AD-bots? After all, they could work 18-hour days, don’t need health care benefits, and can disseminate any message their employer wants. It will be easy replace a recommendation like “SGLT-2 inhibitors in diabetes can reduce cardiovascular and renal disease as well as lower glucose” with: “SGLT-2 inhibitors are extremely expensive and increase our drug budget. Use metformin or sulfonylureas whenever possible.  So if we have a few years to prove that actual people still have a vital role to play in helping practitioners make better decisions, what can we do?

Those are values that endure and can distinguish our work from a sophisticated set of algorithms. Best of all, they can’t be changed if whoever is in charge overwrites a few lines of code to maximize some other agenda, or if the algorithms just make stuff up. Biography.

Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Founder & Special Adviser, NaRCAD Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief Emeritus of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist, geriatrician, and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use, particularly in the elderly. Read More.  Jerry Avorn, M.D. Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School Co-Founder & Special Adviser, NaRCAD Tags: Evidence Based Medicine, Jerry Avorn Inside the world of academic detailing, we’re all convinced of the clinical power of information transmission when done well, and of the harm that can result if it’s done badly or not at all. But outside our mighty little community, many are skeptical about whether pushing out accurate evidence really has such enormous effects. A silver lining of Covid-19 as it recedes a bit into the rearview mirror is that the experience can help us put some of those questions to rest once and for all. Many lives were changed by the effective, accurate transmission of medical reality about the virus, how to prevent its terrible consequences, and how best to treat people who are infected. Thousands of doctors and millions of patients were offered and acted on accurate information about covid, and the point was nailed down by its counter-factual: the millions of patients (and yes, some doctors and health care professionals as well) who received and acted on bad information, with tragic consequences. It was the same virus, more or less, the same vaccines, the same effective and ineffective treatments: sort of a controlled study in which effective transmission of evidence-based facts was lifesaving, and its opposite was often lethal.  Covid was just the most dramatic and recent example of issues that all of us interested in academic detailing have been grappling with for years. It was like a student coming to class one day to confront a surprise pop quiz that will determine three-quarters of the grade. Those who had been diligent all semester could deal with it handily, while those who hadn't been paying enough attention are astonished and devastated. It’s the same for the transmission of clear information about most of the medical conditions our programs confront every day. The pandemic was just the most striking recent example of the good effects of getting this information-transfer right, and the terrible consequences of getting it wrong. We've seen this movie before, in preventing and treating cancer, diabetes, heart disease, maternal and infant mortality, and a host of other conditions for which we have good preventive and therapeutic options to teach about to save lives (and huge costs) by handling that information transfer well, or lose lives and treasure if we do it ham-handedly.  It's been estimated that by early 2022, the risk of illness and death from Covid was determined more by the flow of information than by the biology of the virus. That sounds dramatic, but it’s probably been equally true for years for the other conditions noted above. The pandemic was like a controlled experiment: when confronted by the same infectious agent (more or less) and the same preventions and treatments, some health care systems and communities did much better than others. True, the problem was often lack of access; but another major cause was lack of good transmission of accurate knowledge. This should be a bracing call to action for academic detailing programs as well as the healthcare delivery system as a whole. If the effective dissemination of accurate, actionable facts can play such an important role in infectious disease, cardiovascular illness, diabetes, pediatrics, obstetrics, and nearly every other branch of health care, the good news is that the “pop quiz” of Covid that we’ve just lived through can remind us how much we can do to enhance that flow of education to transform the best science into the best practice – as well as the awful consequences of getting it wrong. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation! Biography.

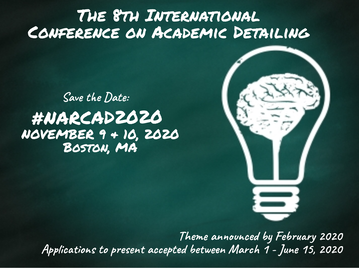

Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Founder & Special Adviser, NaRCAD Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief Emeritus of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist, geriatrician, and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use, particularly in the elderly. Read More. Anna Morgan, MPH, RN, PMP, NaRCAD Program Manager Tags: Conference, COVID-19, Deprescribing, Diabetes, E-Detailing, Elderly Care, Health Disparities, HIV/AIDS, International, Jerry Avorn, Mental Health  Map of where NaRCAD2020 attendees tuned in from Map of where NaRCAD2020 attendees tuned in from Over 240 members of our worldwide community came together to be a part of something special--our 8th annual conference, and our first in a virtual setting. We were able to expand our reach and overcome barriers like travel time and financial constraints that have prevented our colleagues from attending previous conferences. There was a palpable sense of positivity, enthusiasm, and resilience, especially in a virtual space. We’re so proud of evaluations that cited a renewed sense of passion and commitment to AD based on the new lenses we applied to our programming, including comments about feeling “empowered” to continue this work in the year ahead (even amidst inevitable Zoom fatigue.) Check out our highlights and access all event resources below and on the Conference Hub.

With so many of you expressing a continued need around more of our peer working sessions, we’ll be focusing largely on that in 2021—we can’t wait to support your work this year. In the meantime, tell us what you need to make next year a success. See you in 2021. The NaRCAD Team Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Director, NaRCAD Tags: COVID-19, Detailing Visits, E-Detailing, Jerry Avorn The pandemic has changed everything about our lives and our work. Some occupations have been able to adapt to the new abnormal, such as programmers and financial traders. Others have found it harder to do their jobs as before, like brain surgeons and academic detailers. For the latter, in a socially-distant, avoid-human-contact world, how can we pursue an activity that has as its very definition in-person, interactive communication? Academic detailing programs around the country and the world have been grappling with this challenge. And unlike our colleagues the brain surgeons, we have been able to come up with some plausible solutions, even if nothing is quite the same as being up close and personal. We’ve been learning about the virtues and limits of Zoom/Skype/WebEx. If we’re paying attention, using them can bring into sharp focus the central aspect of interactivity, on steroids. It’s a little like becoming a better runner by strapping weights on your ankles (or so my athletic friends tell me). A non-adept academic detailer can mis-use a Zoom encounter even worse than a face-to-face one: “Sit still for 20 minutes while I do this presentation at you.” That will fail on a platform even more calamitously than it does in person. (One clue is when the prescriber mutes their video to read their e-mail.) But if we’re open to it, the e-encounter can focus our attention even more on whether we’re learning where the clinician is coming from, getting feedback, actively asking what sub-topics they most want us to cover. The artificiality and forced intimacy of a screen-to-screen encounter, and the reason we currently have to do our work like this, can also focus us even more on another key aspect of academic detailing, empathy. “How are you holding up?” or “I bet COVID has really changed your practice” are opening statements that can address the 800-pound virus in the (virtual) room, acknowledging the obvious strangeness and discomfort that afflict so many conversations in these awful times. On a more concrete level, pandemic-style education is also forcing us to come up with new ways to use our educational materials. What to do when you can’t focus a practitioner’s attention on a particular graph or table you’re showing them because they’re dozens of miles away? Displaying a PDF of a document and whizzing around your cursor is one easy, but primitive solution. What about presenting a list of topics hot-linked to a detailed display for each? Or completely re-formatting our materials (stop moaning) for better adaptability to a computer screen?  Those of us who also used to teach in classrooms have learned that with a little work (ok, a lot of work) coronaeducation can even be better than what we’ve been used to doing: using links to video clips or animations, real-time interactive polling, techniques that maybe we could have been using in the classroom, but weren’t. Another key advantage of academic e-Detailing, if we can figure out how to make it work well, is the prospect of having a virtual visit with a clinician without the sunk time of getting to their office – a major enhancement in working with practitioners who may be an hour’s drive or more from the educator’s base. The benefit for our field in productivity and cost-effectiveness could be considerable. Contrary to naïve beliefs that “Soon everyone will be protected by the vaccine and we can get back to normal,” this virus probably won’t let us return fully to the old ways any time soon. Instead, it will force us to mutate our work to cope with it. And in the process, not only will we be able to continue our work, we may even discover better ways of doing it. Be strong and stay safe. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation! Biography.

Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Director, NaRCAD Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief Emeritus of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist, geriatrician, and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use, particularly in the elderly. Read More.  Copyright Gifford Productions https://giffordproductions.com/ Copyright Gifford Productions https://giffordproductions.com/ Please refer to our Conference Hub page through narcad.org for all conference related videos and slides, which are available as of December 2nd, 2019. by Anna Morgan, RN, BSN, MPH, NaRCAD Program Manager Tags: Conference, E-Detailing, Jerry Avorn, Program Management Our team at NaRCAD was proud to host the 7th International Conference on Academic Detailing on November 7th and 8th, 2019 in Boston to a sold-out crowd of health professionals engaged in clinical outreach education. With this year’s theme emphasizing collaboration and innovation, our Director, Dr. Mike Fischer, kicked off Day 1 of NaRCAD2019 by reflecting on the past decade of NaRCAD’s work, while also discussing our exciting plans for the future, and highlighting the importance of enhancing connection between attendees to support their work ahead. Dr. Melissa Christopher, National Director for the Veteran Affairs (VA) Academic Detailing Services, was next to take the stage as the Day 1 Keynote Speaker. She provided the audience with an overview of the current work by the Department of Veterans Affairs National Academic Detailing Service and how it supports a High Reliability Organization culture. She also spoke of the future of academic detailing at the VA, which includes expanding their reach with virtual detailing (“e-detailing”) and advancing their electronic health records through ordering safety alerts and real-time PDMP data.  Copyright Gifford Productions https://giffordproductions.com/ Copyright Gifford Productions https://giffordproductions.com/ Other day 1 highlights included an expert panel presenting on the successes and challenges of implementing e-detailing within their programs, sharing stories and insights about when, why, and how to connect virtually with providers. Our small group breakout sessions explored the fundamentals of academic detailing, with sessions focused on the basics of an academic detailing visit, how to identify and apply the most reliable sources of evidence-based research, and how to successfully lead an academic detailing program. Day 1 also included our annual “lightning round” of Field Presentations, a session that highlights aspects of recent academic detailing interventions. Topics included the use of academic detailing to improve maternal and neonatal health through safer opioid prescribing, the effects of academic detailing on pediatric antipsychotic prescribing in the Medicaid population, and increasing access to Nalaxone in New York City through academic detailing. The afternoon also included a talk on Aetna’s opioid strategy and ongoing initiatives, with a focus on leveraging provider and system relationships to incentivize physician engagement and catalyze behavior change.  Copyright Gifford Productions https://giffordproductions.com/ Copyright Gifford Productions https://giffordproductions.com/ Dr. Jerry Avorn, Co-Director of NaRCAD, ended the Day 1 presentations with his Annual Academic Detailing Talk, addressing the importance of moving beyond the silos that exist in most healthcare settings, and how academic detailing can encourage the integration and collaboration of roles and initiatives to create synergy. That collaboration and synergy was illustrated during our evening’s Networking Reception, where we launched our new Mentor Match Program to great success, pairing those just starting out in the field with mentors who are part of more established programs. Day 2 provided similar opportunity for exploration and dialogue about program expansion. We kicked off with Keynote Speaker Tupper Bean, Executive Director from the Centre for Effective Practice (CEP). He discussed CEP’s journey to sustainability as an independent, not-for-profit organization, and reminded the audience that sustainability is a parallel process, not an “add-on”. To further explore sustainability, our Day 2 Plenary highlighted capacity-building strategies, best practices, and opportunities for expansion in clinical outreach education programming.  Day 2 Field Presentations provided opportunities to learn about more active AD programs, including topics such as identifying barriers to opioid prescribing through academic detailing, a team-based model and approach to AD, and a new AD campaign exploring cannabis as an alternative tool for patients experiencing pain. Our afternoon wrapped up with workshops focused on relationship-building for program sustainability, understanding stigma when supporting patients with opioid use disorder (OUD), and building AD campaign materials with limited resources. We’re grateful to all those who attended, and beyond the 2 days of connection at the conference, we at NaRCAD are committed to creating continuous opportunities for connection, support, and collaboration among all of you who make up our incredible network. Keep an eye out for our Annual Community survey, which we’ll send you in early December to find out what you need as you make an even greater impact in 2020! -The NaRCAD Team  Tags: Jerry Avorn The genius of the American health care system is its fragmentation. And by ‘genius,’ I mean evil genius, or demented genius. And sadly, also ‘very stable genius,’ since that awful fragmentation has been stubbornly resistant to change. It’s a great way to maximize revenue and expenditures, but not the best way to provide care to patients – and it leads to much of the poor care and unaffordable costs that we face. In many organizations caring for patients over 65, their medication use is stripped away into Medicare drug benefit plans separate from the way the rest of their clinical care is paid for and organized. Many payors in the private and public sector carve out the use of drugs for specific conditions, removing it from the organization and payment for the care of the illnesses those drugs treat. Outside integrated health care systems, in many settings the content and costs of prescribing decisions live in a pharmacy silo separate from ambulatory care, which itself is often a world apart from inpatient care, with all of these sectors de-coupled from assessment of clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction. But sick people don’t come in silos, and the drugs we prescribe for them drive hospitalization and other clinical outcomes and the enormous human and economic costs of both.  Academic detailing can help pull these domains together in a way that can make medical care more person-based and evidence-based, as well as more cost-effective. The AD interventions that work best start from the global perspective of the practitioner: how to diagnose and care for a given clinical problem, whether it’s Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, or incontinence, rather than focusing narrowly on simple medication use questions (“Don’t prescribe Drug X; Drug Z isn’t on the formulary”). This holistic approach is what clinicians and patients need and want, and the one most likely to bring about optimal care decisions. Such a “beyond the drug silo” approach also has implications for the content and focus of the printed clinical materials our programs use, as well as the interactive approach employed by the outreach educator in these programs. Focusing on silo-busting can also help the academic detailer be seen as a valued colleague helping the clinician improve overall patient care, rather than as a nag, a busybody, or a scold. And as the US health care system continues its slow transition away from the evils of fragmentation to a more rational approach that focuses more on integration of care and less on widget-based revenue maximization, the comprehensive, clinical outcome based vision of academic detailing will increasingly help to pull all the pieces back together where they belong. Want more? Peruse the archive of Jerry's pieces here on DETAILS. _____________________________________________________________ Biography. Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Director, NaRCAD Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use. Read more.  Tags: Detailing Visits, Evidence-Based Medicine, Materials Development, Jerry Avorn Here’s the good news: academic detailing is becoming so widely accepted that everyone wants to help provide the evidence that is disseminated. That’s also the bad news; worrisome examples range from the grotesque to the sinister. One eminent health policy expert wanted to know how much it would cost to put together a nationwide academic detailing program (my heart leaped) that would be underwritten by the pharmaceutical industry (dammit). Prescription drug management (PBM) companies now offer so-called academic detailing services as part of their contracts with payors to oversee drug choices and spending. Sounds good until one realizes that a large chunk of PBM revenue come from payments by manufacturers to move market share to their products. So much for communicating evidence that is neutral, unbiased, and non-commercial. You’d think we’d have learned our lesson by now. Do universities or insurers or government fail to offer enough continuing education about prescribing? No problem, drugmakers will be more than happy to fill the gap, either for free or at amazingly low cost…. often with really great food. That local clinical expert who shows up at Grand Rounds to provide an overview of all the new treatments for diabetes, at no cost to the hospital? Don’t ask who’s paying him to be there. And those convenient smartphone apps that provide so much handy dosing information for any drug you can think of? All you have to do is read the commercial messages that pop up on your way to the data, as the vendor promises its pharmaceutical sponsors the chance to "embed your brand message at multiple points across the care continuum."  There is a solution to the concern about who’s providing the content for academic detailing programs, and it’s much easier than figuring out whether a particular Facebook ad is brought to you by a Russian bot. Just expect that any purveyor of AD information will reveal clearly all the financial ties it and its authors have with any drug or device maker, in relation to program sponsorship as well as the creation and editing of the clinical content. After years of being misled about hidden data on adverse events or failed studies, we’ve developed a higher set of expectations about disclosing all information about clinical trials, and the need to reveal authors’ financial ties for published studies. Those same higher standards must also be applied to academic detailing programs, so that its audiences will know whether the material is the carefully vetted work of a team of unconflicted reviewers who don’t work for any manufacturers, or is instead yet another terribly sophisticated new way to market particular products. Want more? Peruse the archive of Jerry's pieces here on DETAILS. _____________________________________________________________ Biography.

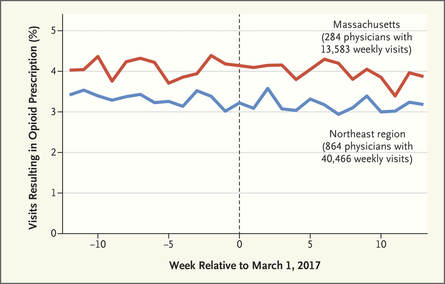

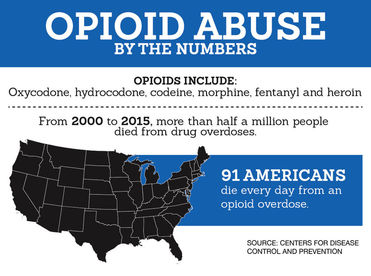

Jerry Avorn, MD | NaRCAD Co-Director Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist, geriatrician, and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use, particularly in the elderly. Read more.  Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Director, NaRCAD Tags: Detailing Visits, Evidence-Based Medicine, Health Policy, Jerry Avorn, Medications, Opioid Safety Of all the medication use issues facing the U.S., the most pressing is of course that of opioid mis-prescribing. When the anatomy of that mis-use is dissected, it becomes clear that the principles and methods of academic detailing are especially well suited to addressing this crisis, for several reasons.  First is the problem of information deficit: before the mid- to late-1990s, practical issues of the assessment and management of pain were often poorly covered (or not at all) in most medical school or residency training programs – so there’s a lot of good that can be accomplished by simple personalized knowledge transfer, to start with. Second is dealing with the contamination of dis-information: the growing documentation of the fact that sales reps for OxyContin, for example, actually under-stated the drug’s risks and over-stated its potential indications when describing their product to prescribers – distortions for which the company had to pay $600 million in penalties. Third is the fact that for this therapeutic category more than for most others, a prescriber’s attitudes and motivations play an especially important role. These can involve “non-scientific” issues such as:

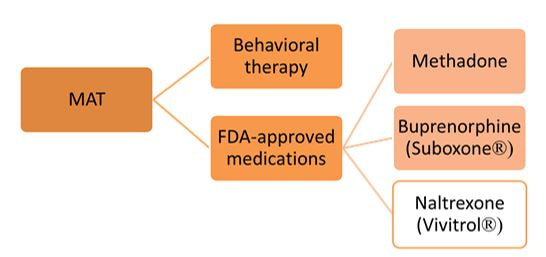

There is ample evidence that simple “gotcha” letters accusing a prescriber of opioid over-use have no effect. Similarly, draconian restrictions imposed by governments or health care systems limiting the amount of opioid that can be prescribed to a given patient clearly run the risk of under-treating genuine pain – a grotesque example of health care rules that seem guaranteed to increase patients’ suffering. Evidence-based guidelines, such as those promulgated by the CDC, are fine as far as they go, but most doctors haven’t read them, and even fewer have integrated them into their practices.  But a well-trained, skilled academic detailer can interact with a prescriber to understand just what issues lie behind the apparent misuse of opioids by that physician, and present a set of interactive messages tailored to those particular needs. This will involve constructing a personalized blend of new knowledge transfer, dis-information detoxification, practice facilitation (including help accessing Prescription Drug Monitoring Program data less burdensomely), accessing local resources for help in patients with opioid use disorder, and assistance with patient education.  A similar approach could also be enormously helpful for encouraging naloxone prescribing and improving the care of patients with opioid use disorder, including medication-assisted treatment, where information deficits and attitudinal issues are even more prominent. Together, this kind of individualized outreach education can accomplish far more than mailed guidelines, accusatory nastygrams, or legal restrictions – and in doing so, do more to improve patient care and reduce preventable misery than can be expected from more old-fashioned interventions.  Biography. Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Director, NaRCAD Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use. Read more. Navigating a Disorienting Healthcare Landscape | Jerry Avorn, MD, NaRCAD Co-Director  Tags: Evidence-Based Medicine, Health Policy, Jerry Avorn, Medications First, about the grammar. Readers under 65 will be forgiven if they never heard of the daytime television quiz show “Who Do You Trust?” that aired from 1957 to 1963. In it, male contestants were asked if they wanted to answer a question or whether they ‘trusted’ their wife to do so. Concerns by snarky little kids like me that it really should have been “Whom Do You Trust?” did not diminish the show’s popular appeal. Gender issues went totally undiscussed. All grown up now and confronting a changing health care landscape, that still-sometimes-snarky little boy often wonders, as do many of my clinician colleagues, who can be trusted in the world of medical information, especially in relation to prescription drugs. Gone are the simpler times when one had to worry only about whether the drug ads and sales reps were really presenting a balanced picture of all the evidence, which was a hard enough challenge.  We now know that we also have to be concerned about off-label marketing campaigns offering impermissible (and often downright deceptive) statements about efficacy – excesses for which over $16 billion has now been paid to state attorneys general in legal penalties and settlements. As I’ve noted previously, the courts and the FDA are also moving toward much more permissiveness with company claims about efficacy and safety. And in last year’s 21st Century Cures Act, Congress instructed the FDA to be more open to accepting lower standards for drug approval.  Then there are newer sources of information whose trustworthiness is not always clear. More and more, this includes the prescription benefit management (PBM) companies, which seem to be holding on to an ever-larger fraction of the funds flowing through their rich payment pipelines, yet provide little transparency about who gets to keep what rebate dollars, and for what reason. Once billed as cost-savings protectors and comparative effectiveness gurus, the PBMs are under increasing scrutiny, and asked to make their financial data transparent and to clarify just who’s saving what for whom (or is it ‘for who?’).  Nor can we always be sure what angle the payors are playing. Why is Drug A on the formulary, but not its sibling Drug B? It may be an astute purchasing decision, or just the result of a rebate hack. And how much are prior authorization rules and growing co-payments designed to promote evidence-based care, or other less worthy goals? Even clinical guidelines put out by third parties vary from the most rigorous to pretty sketchy.  This leads to one good answer to the ungrammatical question in our title. With these galloping changes in an ever-more marketplace-oriented health care system, every prescriber needs and deserves a smart, superbly informed colleague to rely on to get the best possible syntheses of the clinical evidence – someone who has no other agenda or motivation other than getting the facts right and transmitting them faithfully. Each year, we can take less comfort in counting only on FDA-approved indications, or payor policies, or PBM choices, or advertised claims. The more compromised each of these sources becomes, the more we’ll need ‘honest brokers’ like well-trained and un-conflicted academic detailers, whose only duty is to communicate the fairest evidence summaries as effectively as possible. Like lightweight clothing in an era of global warming, it’s a need that’s only going to increase. Thoughts? Reactions? Sound off below.  Biography. Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Director, NaRCAD Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use. Read more.  Mike Fischer, MD, MS, NaRCAD Director Tags: Conference, Director's Letter, HIV/AIDS, Jerry Avorn, Opioid Safety, PrEP, Training Fall is the season for conferences, and the most exciting one for us is #NaRCAD2017: Combatting Threats to Optimal Care! This year’s conference is a great chance for everyone interested in AD to learn more, whether you’re part of a long-standing program or just beginning to learn about the versatility and effectiveness of implementing this strategy to improve health outcomes. Our agenda is up, so take a peek, and register if you haven’t yet!  The keynote presentations will provide critical insights for creating and sustaining AD programs in different settings. Dr. Zoe Edelstein will kick off Day 1’s programming, representing the New York Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. This keynote will teach us about their public health detailing intervention to increase use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The New York program was originally founded in 2002, so Dr. Edelstein’s presentation will help anyone from a public health background understand how to both develop and sustain AD, and to adapt it for new and pressing health challenges.  Dr. Carol Havens from Kaiser Permanente will provide a detailed overview of the longest-running AD program in the US, a program that was developed with input from Jerry Avorn soon after the original AD studies were published. We look forward to being inspired by lessons learned from a leading integrated health care system’s ongoing commitment to improving the quality of care around opioid safety with clinical outreach education. The rest of our conference agenda draws almost entirely from proposals submitted by members of our NaRCAD network – we received twice as many proposals this year! We’re looking forward to our “Field Presentations” sessions, featuring empiric results from detailers on the ground; expert panelists from the CDC, state departments of public health, and clinical care sharing important impressions on clinician stigma on the critical issues of HIV prevention and opioid safety; and breakout sessions covering many of the practical issues and challenges that detailers face when bringing best evidence to clinicians. Of course, for many of us, the highlight of each conference is the annual update from Jerry Avorn on the state of AD--see his recent blog piece, “Who Do You Trust?” for a preview of what’s to come!  The NaRCAD team is excited by the knowledge that integral opportunities, connections, and partnerships will be created at our unique 2-day event. But as excited as our team and our extended community may be about the conference, it’s not the only terrific development underway at NaRCAD this fall. We’ve continued to provide training and support for groups from around the country and the globe, with 2 trainings in the techniques of AD this past September, and more planned this fall and winter! Keep your eyes on our Training Series page for the official announcement of our Spring 2018 AD techniques training, and contact us at any time about opportunities and resources to support your AD program. See you soon, -Mike Biography. Michael Fischer, MD, MS, NaRCAD Director

Dr. Fischer is a general internist, pharmacoepidemiologist, and health services researcher. He is an Associate Professor of Medicine at Harvard and a clinically active primary care physician and educator at Brigham & Women’s Hospital. With extensive experience in designing and evaluating interventions to improve medication use, he has published numerous studies demonstrating potential gains from improved prescribing. Read more. Tags: Evidence-Based Medicine, Health Policy, Jerry Avorn, Medications Listen closely, and you’ll hear the other shoe dropping. For several years FDA has been besieged by litigation brought by drug makers and their supporters which argued that the agency’s limiting companies’ promotional claims violated those corporations’ First Amendment-protected rights to ‘commercial free speech.’ Then the 21st Century Cures Act signed by still-President Obama in December of 2016 authorized FDA to consider less demanding standards in approving medications. 2017 began with a new administration vowing to free the pharmaceutical industry from the onerous regulatory burdens of the FDA. Now all these forces are coming together in a worrisome confluence of regulatory derangement.  The House Energy and Commerce committee in mid-July held hearings on how best to implement the Congressionally mandated loosening of drug approval standards set forth in the “Cures” act. At the same time, the new FDA Commissioner has argued that FDA’s “public health mandate” should be met by relieving manufacturers of some of those troublesome requirements to demonstrate clinical benefit, in order to get drugs to the public more easily. At the same time, he noted, as FDA reduces the complexity and duration of the drug approval process, this speeding of new drugs onto the market will help contain their high prices. Nevermind that FDA’s approval process is already the swiftest in the world, clocking in at a mere 6 months for priority decisions. And nevermind that the cost of the regulatory process accounts for only a small portion of medication prices. And just ignore the fact that worrying about cost never has been part of that agency’s mandate. Justifying the reduction of FDA’s regulatory standards to meet its “public health mandate” is a troubling Orwellian development that is likely to have exactly the opposite effect. It is eerily reminiscent of the notorious Vietnam-era claim by the military that a village “had to be destroyed in order to save it.” Invoking FDA’s public health mission to justify approving drugs that have not been adequately shown to help patients is both bizarre and irrational. These developments raise the ante for evidence-based prescribing in general, and for academic detailing in particular. Most clinicians and health care systems are not yet aware that FDA approval may become an eroded imprimatur to guide medication decisions, and most people will continue to believe that pharmaceutical company claims have to pass muster with FDA for their accuracy, even as this becomes less and less true in the coming years.  Even if we cannot stop these disturbing developments, we must at least make sure that they are understood by our colleagues in medicine, so that academic detailing services – by definition rigorously evidence-based and non-commercial – can play an increasingly large role in informing prescribing decisions, as an antidote to these worrisome ongoing developments. Share your thoughts in our discussion forum below.  Biography. Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Director, NaRCAD Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use. Read more. Sharing the History & Origins of AD via Jerry Avorn's 2017 NEJM Article Tags: Evidence-Based Medicine, Jerry Avorn  Thirty-eight years ago, a US federal research agency issued a request for proposals on “Improving the Quality and Economy of Prescription Drug Use.” Recently out of my residency and concerned about the mismatch I was seeing between the best evidence and prevailing patterns of prescribing, I suspected that the problem might result in part from an imbalance in the effectiveness of communication coming from commercial vs academic sources. The pharmaceutical industry was impressively adept at sending well-trained change agents (drug “detailers”) to provide information about company products engagingly and interactively to physicians in their offices, in order to increase product sales. Academics, by contrast, who may have had a more impartial and thorough understanding of the evidence, tended to be passive and inelegant communicators, standing behind podiums in optional continuing education courses, delivering one-way didactic presentations in darkened rooms, often doing little to change actual practice. Click here to read the whole article at NEJM's "Piece of My Mind" Archive. Jerry Avorn, MD Harvard Medical School; Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; Co-Director, NaRCAD JAMA. 2017;317(4):361-362. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.16036 “There are no facts, only interpretations.” Friedrich Nietzsche “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.” William Butler Yeats “A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.” Mark Twain  The late Senator Patrick Moynihan (D, NY) once famously noted, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinions, but not to his own facts.” Leaving aside the more contemporary position that women are entitled to opinions too, in our strange new sociocultural milieu Moynihan’s adorable truism now suddenly seems, like certain body parts, to be totally up for grabs. Global warming is a hoax; China devalues it currency; Hillary Clinton murders her enemies and runs a pedophile ring out of a Washington pizzeria. A presidential spokesperson re-frames a lie as an “alternative fact”; shouted mistruths seem to get more public attention than established realities. For growing audiences, rogue fake news websites seem to carry the same credibility as the New York Times or The Washington Post. And now this strange new wonderland of unreality is poised to redefine communication about medical facts, particularly about drugs.

All this will make the provision of rigorously evaluated, evidence-based knowledge about anything, especially the effectiveness and safety of medical interventions, an increasingly needed service. Prescribers will be less and less able to feel comfortable that FDA approval means that a drug has been shown to actually benefit patients. And we always knew that sales reps were adept at putting their products in the best possible light; now they’ll be able to toss out not-quite-true promotional quasi-factoids with more and more impunity. This is the medical world in which academic detailing programs will exist for the foreseeable future. And the more health care is provided in an environment of alt-facts and distortions, the more our sources of unbiased, non-commercial information will be valued and vital. We have our work cut out for us. Biography. Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Director, NaRCAD

Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use. Read more. As I write this in mid-January, it is difficult to know how the health care system will be transformed in the coming weeks, months, and years. But one thing is clear: the new administration and Congress are intent on repealing the Affordable Care Act, and they will have the votes in Washington to do so. Despite their holding this policy position for six years, followed by a long (if issues-light) campaign season, it is not at all clear what will replace it. But one thing is certain: the new administration is committed to reducing federal support for health care for enormous numbers of American citizens. “Better coverage and lower costs” is more bumper-sticker rhetoric than plausible policy, and doesn’t meet the basic criteria of arithmetic. This means that all those who care for patients in the U.S., as well as policymakers, will be forced to live under the yoke of that awful cliché, “doing more with less.” (Our colleagues in Canada and overseas must be reading this message from the richest nation on earth with a mixture of horror and pity.) Appropriate clinical decision making is about to be transformed from a noble goal we should all strive for to a literal matter of life and death. As the ranks of the uninsured and underinsured swell, prescribing a costly drug when a more inexpensive one would work as well will increasingly mean that patients without adequate coverage will simply be unable to afford treatment for their atrial fibrillation, hypertension, or heart failure. The aftermath of the November election will convert a bumpy, imperfect patchwork of coverage into a public administration catastrophe, soon to be followed by a public health debacle.  These changes will transform the active provision of evidence-based, non-commercial information about clinical care from a smart choice for quality improvement to an urgent requirement. Practitioners who care for the millions of patients whose coverage is legislated away will desperately need the very best information about comparative efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Most of us engaged in academic detailing programs have shied away from emphasizing cost-containment as a primary feature or goal of such programs, and for good reason. But just as battlefield medicine often has to dispense with the niceties of office practice to address front-line emergencies, we will need to consider the possibility of “battlefield academic detailing” in the coming year to help deal with the widespread health care financial trauma that patients throughout the U.S. will be confronting, along with their health care professionals. Most of us in American medicine – patients and clinicians alike – will find our hazard ratios going up, and our quality of life going down. Now more than ever, it will be imperative to communicate the best science as effectively as we can.  Biography. Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Director of NaRCAD Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist, geriatrician, and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use, particularly in the elderly. Read more. Jerry Avorn, MD | NaRCAD Co-director Tags: Detailing Visits, Evidence-Based Medicine, Jerry Avorn, Primary Care There was a brief shining moment starting in the early 1970s, when I was finishing medical school, that lasted into about the mid-1980s. Primary care physicians (PCPs) seemed poised to rise above their lowest-in-medicine stature to become recognized for playing a central role in the entire health care system (as, of course, they had been doing all along). In medical centers throughout the country, growing interest in ‘health maintenance’ and its accompanying insurance designs seemed poised to catapult PCPs from the role of nerds to quarterbacks. Then, for reasons we don’t have the space to discuss here, in the following years in many settings, the quarterbacks got recast as gatekeepers, and then as switchboard operators. Delivering primary medical care remained as innately vital and sacred a job as ever, but the stature and daily work of the PCP (with the second P now standing for ‘provider’) became degraded in many settings. Morale sank, and PCP burnout and dropout became more common. What does all this have to do with academic detailing? A lot. One of the most frequent and visible ways that the quarterback-to-gatekeeper degradation has developed is in the role of clinical decision-making – for medications most often, but also about test ordering, specialist consultations, and many other choices the primary care clinician faces daily. In the Olden Times, which still survive in some pockets of our pathologically heterogeneous coverage system, these decisions are still left in the hands of the PCP, and are still made well or poorly by individuals. But increasingly, such choices are driven by formularies, prior authorization requirements, algorithms, and other restrictions. Sometimes these are thoughtful, evidence-based guidances that are useful antidotes to the occasional wild and crazy choices some practitioners occasionally make – ‘freedom’ which can on occasion lead to potential harm to both patients and health care budgets. But sometimes the restrictions are simple-minded, financially-driven, and disrespectful of the needs of specific patients and the nuanced judgment of the individual clinician. That’s where academic detailing comes in. There will always be a place for formulary limitations and restriction of the worst non-evidence-based decisionmaking. But wouldn’t we all rather live in a medical world in which decisions are primarily shaped by the informed decisions of a well-trained health care professional, updated through discussion of the latest data? Especially if that information was provided by another savvy clinician equipped to have a back-and-forth conversation about the basis and the pros and cons of trial findings, guidelines, and observational research? That would help primary care clinicians make better decisions without all the limitations of arbitrary insurance requirements, or computer-based algorithms that sometimes function as if they know Mrs. Johnson better than her doctor does. It could also pave the way for wider adoption of the evidence-based recommendations that the more enlightened policies seek to achieve. And clinicians could again feel more like the health care professionals we spent so many years learning how to be. Join us for Dr. Avorn's annual conference talk at #NaRCAD2016: Innovations in Clinical Outreach Education.  Biography. Jerry Avorn, MD | NaRCAD Co-Director Dr. Avorn is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (DoPE) at Brigham & Women's Hospital. A general internist, geriatrician, and drug epidemiologist, he pioneered the concept of academic detailing and is recognized internationally as a leading expert on this topic and on optimal medication use, particularly in the elderly. Read more. The exponential increase in computing power and data storage capacity, coupled with the sharp decrease in data processing costs, have made possible an era of ‘big data’ that is transforming many aspects of life and commerce. In health care, this evolution is enabling access to information that was impossible to imagine in the era when I first began this work when most prescriptions and test orders were still written on little scraps of paper. As applied to academic detailing, this growing capacity opens up a veritable armory of double-edged swords. Knowing what doctors are ordering: This information has always been an important advantage of the pharmaceutical industry, which routinely buys the detailed prescribing records of specific physicians from intermediaries such as IMS, who in turn purchase these records from nearly every pharmacy in the nation. In the hands of an agile pharmaceutical representative, knowing a doctor’s drug preferences can be a powerful tool in shaping a promotional message tailored to that person.

Many of us in have had mixed views about the use of such data. On the one hand, it can make possible a more precisely focused discussion about optimal ordering of tests and treatments that is based on a given practitioner’s actual behavior. On the other hand, the approach comes with several risks. One is the concern that clinicians may feel “spied upon” – a problem that doesn’t seem to come up much in industry visits. This in turn can divert the conversation to discussion of “Why are you visiting me?” rather than a conversation about optimal patient care. Data feedback to clinicians also degenerates frequently into he said-she said debates that often come down to “My patients are different!” We welcome feedback from academic detailing programs on how this use of data has worked (or hasn’t) in their own settings. What patients are (or aren’t) doing: The computerization of dispensing records opened an era of hitherto-difficult research on patient adherence to their medication regimens, with generally depressing findings of low adherence. The full import of this rampant epidemic of non-compliance is still not well understood by most prescribers. The rapid growth in mobile and wearable technologies that capture physical activity and other lifestyle choices provides another potential source of data on patient behavior, but the best applications of this information are even less well understood. In principle, academic detailing programs embedded in health care organizations can provide feedback to clinicians on how much or how little their patients are taking medications as directed or complying with other medical advice, and – more important – what to do about it. Is this a useful component of the educational encounter? Again, we would welcome hearing how this use of big data to provide feedback on adherence or patient behavior does or doesn’t fit into the work of ongoing academic detailing programs.

In the coming years, we will see even greater access to terabytes of data on who is ordering what, and what patients are doing with their prescriptions and other treatments. Used well, this technological revolution can provide added power to programs designed to improve that clinical decision making. Jerry Avorn, MD, Co-Director of NaRCAD, Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women's Hospital Tags: Evidence-Based Medication, Jerry Avorn, Medications  Consider the following recent news development: A large multinational company is discovered to have purposely hidden the risks of one of its best-selling products by suppressing information about its adverse effects and presenting only a selective set of data about its impact, to cast it in a more favorable light than was accurate. The magnitude of this distortion was so great that it posed health risks for hundreds of thousands of people throughout the industrialized world. The company admitted guilt and said it would try to do better in the future. No criminal charges were pressed, and none may ever be. I refer, of course, to Volkswagen. Last year, the carmaker was found to have rigged the pollution-control devices in its diesel cars to make it appear they were reducing emissions, but only when the car was being inspected. The rest of the time the autos spewed out pollutants far in excess of the allowed limits. The engineers and executives who perpetrated this enormous hoax were not demons. They were employees of a large corporation who let the need for profit (or shareholder value, a more polite term) push them beyond the limits of accurately presenting data about their products. These things happen in large companies, including drugmakers, who have in the last decade or so had to pay over $15 billion in legal settlements, most of which dealt with such mis-statements of benefits and harms. Nothing personal; it’s just business. Anyone who is shocked about this should go back to review the imperatives of corporate life, as defined by the Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman. In a 1970 article, he noted that “There is one and only one social responsibility of business -- to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits….” Unfortunately, the second half of that sentence is often omitted: “…so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.” In an era of an overstretched and sometimes overmatched FDA, there’s a greater need than ever to present clinicians with an accurate depiction of the good and harm that medications can do. Of course, academic detailing is about far more than just correcting the excesses or misstatements of drugmakers. Our job is to present a comprehensive, un-skewed overview of the benefits and risks of medications and other health care decisions. But in doing so, we sometimes have to address misconceptions generated by some drugmakers who are, I suppose, just trying to give their shareholders a good return on their investment. Whether a company makes cars or drugs, its staff at all levels are under tremendous pressure to increase sales. This can often draw otherwise reasonable employees close to – or sometimes over – the line of what’s deceptive. In academic detailing, we don’t have to worry about sales goals or profit margins. The only currency we need to maximize is accurate evidence; our only “shareholders” are patients and the clinicians who care for them. In a way, that’s the easiest and best part of our jobs.  Attendees share resources during a networking break. Attendees share resources during a networking break. Bevin K. Shagoury, NaRCAD Communications Tags: Conference, Detailing Visits, Jerry Avorn, Opioid Safety, Practice Facilitation The excitement and breadth of content in this November’s 3rd International Conference on Academic Detailing exceed what we can capture in this blog post. The combination of exciting speakers, engaging panelists, expert breakout session leaders, and national and international attendees eager to problem-solve created a forward-thinking event that inspired all of us working on AD and related outreach educational activities. As you reflect on our event's highlights, we encourage you to access on-demand video, speaker biographies, session descriptions, and more at our Conference Hub resource page.  Dr. Coffin of SFDPH and Dr. Fischer of NaRCAD Dr. Coffin of SFDPH and Dr. Fischer of NaRCAD Kicking Day 1 off and setting the tone for the entire event, NaRCAD Director Dr. Mike Fischer warmly welcomed our packed room at Harvard Medical School’s Martin Center by encouraging collaboration, connection, and sharing. Our Day 1 Keynote Speaker Dr. Carolyn Clancy, the CMO of the Veteran’s Health Administration, described the VHA’s work to improve pain management in the veteran population while addressing the challenges of medication abuse and overdose. Dr. Clancy shared strategy and data behind the national effort and the critical role of academic detailing in it, connecting attendees to a big-picture view that can be adopted to look at other health epidemics and interventions. Our first expert panel presented Practice Facilitation in Primary Care. Andy Ellner moderated the session, leading panelists Ann Lefebvre of North Carolina's AHEC Program, Lyndee Knox of LA Net, and Allyson Gottsman of HealthTeamWorks to discuss strategies, contextualize their work in relation to academic detailing and quality improvement, and share their personal approaches to challenges in primary care behavior change. Allyson Gottsman’s much-appreciated analogy that practice facilitation is not unlike “leading a fisherman to a well-stocked pond” resonated with panelists and participants alike. Many attendees who were actively engaged in practice facilitation in their daily work shared that the panel helped them to think about their work in a new way.  Breakout leaders share a moment during the Day 1 session! Breakout leaders share a moment during the Day 1 session! The afternoon’s breakout sessions offered attendees multiple tracks with AD-related topics to explore: deconstructing and analyzing a 1:1 AD visit, exploring the skills needed to manage an effective AD program, and strategizing on ways to identify and harness stakeholder support when initiating a new program or strengthening an existing one. The afternoon closed with two presentations; the first, by Terryn Naumann of the Canadian Academic Detailing Collaboration (CADC), offered participants a view of the power of synergy and teamwork, the historical context of the CADC’s creation and growth, and the future of the collaboration.  Dr. Avorn gives a presentation one Tweeter called "pure gold" Dr. Avorn gives a presentation one Tweeter called "pure gold" The final presentation of the day was a lively one by NaRCAD’s co-founder and co-director, Dr. Jerry Avorn, who identified major obstacles to effective evidence-based communication in the current landscape of healthcare, and provided a future-centered lens through which attendees could envision how academic detailers can address these challenges. A full day of new ideas and connections culminated in a networking reception that gave attendees a chance to relax and connect socially. Day 2’s morning opened with another engaging Keynote Speaker; Dr. Don Goldmann, CSO & CMO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, combined quality improvement theory with personal anecdotes, weaving in real-life examples of successful interventions to provide context and dimension to the theory that underlies all of our work.  L-R Valerie Royal, Joy Leotsakos, Sameer Awsare, Mike Fischer. L-R Valerie Royal, Joy Leotsakos, Sameer Awsare, Mike Fischer. More examples of successful practice change were illustrated by the morning’s Themed Plenary on the Intersection of Public Health and AD. Dr. Phillip Coffin of the San Francisco Department of Public Health shared the success of an intervention focusing on co-prescribing of naloxone to reverse opioid overdose deaths in San Francisco. Another successful AD intervention was presented by Michael Kharfen of the Washington D.C. Department of Health, who highlighted the successful implementation of AD programs to increase HIV and Hepatitis C screening and treatment. The afternoon featured our second Expert Panel, this time on the role of AD within integrated healthcare systems. Moderated by Dr. Mike Fischer of NaRCAD, panelists Joy Leotsakos of Atrius Health (MA), Sameer Awsare of Kaiser Permanente Medical Group (CA), and Valerie Royal of Greenville Health System (SC) shared their experiences using AD in systems at different stages of development. Attendees had the opportunity to discuss this topic further in the afternoon’s breakout sessions, which also included a session on practice facilitation, as well as third session to continue to explore AD and public health partnerships.  Happy to see our colleagues from Norway at #NaRCAD2015! Happy to see our colleagues from Norway at #NaRCAD2015! The conference’s closing discussion was led by Mike Fischer, who thanked not only the speakers, panelists, and session leaders, but the participants, whose willingness to share their experiences within an interactive setting was key in creating solutions to bring back to use in their daily work. The creative collaborations, exchange of resources, excitement in combating challenges in the field, and belief in the importance of AD for the future of healthcare transformation were felt by all at the closing of a very full and thought-provoking event. Our Twitter feed tracks the event’s highlights through #NaRCAD2015, and you can catch our event photo album on our Facebook page. We invite you to explore these topics, learn about our speakers and attendees, and connect with us at the NaRCAD Conference Hub, where you can access on-demand video of all main sessions from the conference. Thank you again to all who attended, and to AHRQ for funding our series. Please stay in touch with us and each other, and continue the conversation and idea sharing below. We hope to see you in 2016!  Jerry Avorn, MD, NaRCAD Co-Director Tags: Detailing Visits, Jerry Avorn, Training Often, in discussing academic detailing programs with current or potential sponsors, the question comes up: “Wouldn’t it be cheaper just to deliver the message to a whole group of clinicians at once, instead of the much more cumbersome process of talking to prescribers one at a time?” Sure, it would be cheaper. So would just mailing (or e-mailing) memos to people telling them what to do, or requiring time-consuming groveling on 1-800-DROP-DEAD prior authorization numbers before a costly resource can be ordered. The problem is that cheaper solutions often don’t work, or don’t work well. We have decades of proof that putting health care professionals together in a darkened auditorium and subjecting them to a PowerPoint Tolerance Test does not reliably change behavior. The main reason that academic detailing relies on one-on-one interactive communication is that it is the best way for the outreach educator to accomplish several key goals:

Well-trained academic detailers understand this, and they use the interactivity to craft a real-time, care-improvement message that best addresses the learning needs (and attitudes and biases!) of the person they’re visiting. Less competent academic detailers force their “targets” to sit still while they administer a canned micro-lecture monologue, which works poorly. They may feel they “got through all the points” they wanted to cover, but if there was no interactivity, no conversation, then the person they were talking at might as well have been falling asleep in a darkened amphitheatre. We know this is the case from decades of experience and scores of randomized controlled trials. We also know, perhaps most compellingly, that when the drug industry wants to change what we know and about its products, it sends people to our offices to talk with us—it doesn’t rely only on the less expensive modalities of mailings, e-messages, and sponsored lectures. So the next time someone suggests that it might be more inexpensive to just gather prescribers into a big room and have someone talk at them for an hour, agree with them. Then point out that it’s also less time-intensive to scarf down a Big Mac than eat a real meal, shoot off a series of emoticons rather than a personalized note, or listen to a ring tone of a Beethoven sonata rather than hear it performed by musicians. Cheaper isn’t everything. Jerry Avorn, MD, NaRCAD Co-Director

Tags: Detailing Visits, Health Policy, Jerry Avorn, Medications For over a century, appropriate medication use in the U.S. has relied heavily on the regulation of what manufacturers can say about their products. One of the first powers given to the Food and Drug Administration when it was created in 1906 was the ability to require that makers of “patent medicines” state what was actually in their products. (Often, it was a mixture of ineffective ingredients laced with alcohol or opium, but accurate information was a start.) Over time, the agency was granted the authority to regulate claims about efficacy and safety that companies made about prescription drugs. This has begun to change, with potentially important implications for academic detailing. Currently drug manufacturers promoting their medications to clinicians are limited to discussing indications for which they have obtained approval from FDA, Last year, however, FDA announced its openness to considering policies to make it easier for drug manufacturers to present doctors with their own views about off-label uses of their products that FDA did not consider appropriate. A follow-up “draft guidance” would similarly open the door for manufacturers to provide information about side effects that differs from the determinations of FDA scientists and outside advisers. Most recently, the agency has revealed plans for a national conference on whether limiting drug-makers’ promotional statements might infringe on these companies’ corporate free speech rights. And a bill that has progressed through Congress, The 21st Century Cures Act, will make it easier for drugs to be approved on the basis of looser standards, including lab tests or other surrogate measures of efficacy rather than actual patient outcomes. These developments will have important implications for academic detailing. If we are entering a period of lessened government regulation of what pharmaceutical manufacturers are permitted to tell prescribers about off-label uses of their products, or their safety profiles, there will be an even greater need for balanced, evidence-based communication to inform medication use decisions. Just as travelers to developing countries that have polluted water supplies often prefer to drink bottled water, clinicians may increasingly feel the need for access to non-contaminated information sources if they can’t be sure what’s coming out of an increasingly de-regulated informational tap. All of us concerned with optimal use of medications will need to monitor these developments closely. If the proposed changes prevent FDA from regulating the promotional claims made by drug manufacturers as closely as in the past, then health care systems and individual practitioners will have increasingly greater need for the more reliable sources of information that academic detailing services can provide. Stay tuned. |

Highlighting Best PracticesWe highlight what's working in clinical education through interviews, features, event recaps, and guest blogs, offering clinical educators the chance to share successes and lessons learned from around the country & beyond. Search Archives

|