|

By Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD An interview with Trish Rawn, BScPhm, PharmD, Clinical Service Director and Academic Detailer, Centre for Effective Practice (CEP). CEP is a not-for-profit in Canada that aims to close the gap between evidence and practice for healthcare providers. Tags: Stigma, Detailing Visits, Substance Use  CEP's COVID-19 Resource Centre CEP's COVID-19 Resource Centre Anna: Hi Trish! Thanks for joining us today. Your team has been working on a number of AD campaigns including, falls prevention, type 2 diabetes, benzodiazepine use in older adults, chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP), and opioid use disorder (OUD). Can you tell us about some of the other recent work you’ve been doing at CEP? Trish: Our team’s academic detailing work is a big part of what we do, but CEP has other supports as well. We create clinical tools and resources on myriad clinical topics where practice gaps have been identified. Our most popular resource has been our COVID-19 Resource Centre to support primary care clinicians in adapting their practice during the pandemic. It’s become a massive resource that has had over 140,000 downloads. Anna: Wow! That’s an impressive amount of downloads. One of the other priority areas where your team has identified practice gaps is OUD. This topic often has a lot of stigma associated with it. Is this something you’ve experienced with the opioid detailing campaigns?  Trish: When we first started detailing on CNCP, opioid tapering, and OUD, there was a lot of fear and stigma among clinicians. They didn’t want to be known as the doctor “prescribing all the opioids.” Some clinicians were concerned that they might get in trouble, and they’d say things like, “I don’t have any of those patients” or “They’re all inherited patients.” Clinicians also sometimes felt like they didn’t want to say the wrong thing to patients, so they wouldn’t say anything at all. We’re all guilty of this and we’ve tried to encourage language like, “Hey, I might be saying the wrong thing here, but let's just start the conversation.” Anna: Just starting the conversation with the right intentions is helpful, even if you don’t get the language completely correct. Have you seen any stigma at the patient level? Trish: We found that patients themselves were experiencing stigma when seeking help and when trying to talk openly about opioids with their clinicians. Family doctors are in a vital position to help patients because they tend to have long-term, trusting relationships with them; they have sometimes taken care of them since they were children. Studies show that when opioid replacement therapy is prescribed by family doctors, there are improvements in patient uptake, patient satisfaction, and treatment success. We wanted to get the clinicians to a place where they felt confident talking with patients about opioids and where their patients felt comfortable sharing their experiences. It may feel like a jump for a clinician to go from, “I'm here to measure your blood pressure and adjust your medications” to “Let's talk about opioid addiction and set goals around tapering.”  CEP's Opioid Use Disorder Tool CEP's Opioid Use Disorder Tool Anna: I can see how talking about OUD might make some clinicians feel uncomfortable. What types of resources has your team developed to support both clinicians and their patients to feel more comfortable having these conversations? Trish: For our academic detailing visits on opioids and CNCP we developed a resource called Talking Points with Patients, which includes scripts for clinicians to handle different scenarios. For example, one of the scenarios is about a patient asking for a dose increase for an opioid, but the clinician not agreeing that a dose increase will help manage their pain. We also have a Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound (SMART) Goals resource to help clinicians set goals with their patients by taking the focus off the pain number scale and focusing on actions like, “What activities would you like to do if you had less pain?” Anna: It’s clear that your team works hard to develop and tailor resources to support clinicians and patients. What kinds of local resources from your community are available for detailers to share with clinicians? Trish: We often help clinicians find local resources through a program called The Healthline, which is a website that connects patients with social supports, like counseling, food, and safety. We’re also lucky to have Rapid Access Addiction Medicine (RAAM) clinics in our community that are a one-stop shop for patients with OUD where they’re assessed, given support and a plan for tapering, and referred to other community services. Anna: It’s so important for clinicians and patients to be linked to local resources and know that they have a community supporting them. Can you share some data about how clinicians reacted to the opioid-specific campaigns overall?  Trish: Absolutely! I can share some key findings from our opioid campaigns. Opioid therapy for CNCP AD campaign (n=475): After the detailing sessions, clinicians indicated they were confident in their ability to have a conversation about tapering when appropriate, even when the discussion was challenging (93.5%). Non-pharmacological and non-opioid alternatives for CNCP AD campaign (n=323): Clinicians indicated that after the detailing sessions they were confident in their ability to help patients:

OUD AD campaign (n=250): Clinicians indicated that the detailing sessions enabled them to support patients with OUD by:

Anna: That’s incredible. It’s obvious that your campaigns have made a huge impact on clinicians. What advice would you give to other AD programs who are supporting clinicians in reducing stigma, especially as it relates to opioids? Trish: I would recommend remembering three key points: Examine your own biases: When developing detailing tools, you need to make sure that you’re aware of your own biases and that your tools include the lens of equity, diversity, and inclusion. This is something we are actively working on incorporating in all our work at CEP. Make space for clinician experiences: It’s important to remember to be sensitive to the clinician perspective. There have been times, especially with opioids, where clinicians have had painful experiences with patients overdosing. Be aware of their perceptions and respectful of the trauma they may have experienced. Know your patient population: Understand who the patients are, the trauma they’ve faced, and the stigma they may endure. Look at the experiences of your team, the clinicians, and the patients you’re working with and try to understand how these different perspectives all influence one another as you develop your resources. Anna: That’s beautifully said, Trish. Thank you so much for sharing about your important work in reducing stigma around OUD. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Trish Rawn is the Clinical Service Director for the Centre for Effective Practice Academic Detailing Service. She is a hospital pharmacist who has been detailing for 6 years on topics such as antipsychotics in the elderly, opioid tapering, chronic pain, diabetes, falls prevention, and benzodiazepine deprescribing. By Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD An interview with Adrienne Butterwick, MPH, CHES, Senior Improvement Advisor and Academic Detailing Project Manager, Comagine Health. Comagine Health is a national, nonprofit, health care consulting firm that works collaboratively with patients, providers, payers and other stakeholders to reimagine, redesign and implement sustainable improvements in the health care system. Tags: Detailing Visits, Evidence Based, Substance Use, Opioid Safety  Anna: Hi Adrienne! We recently saw you present on a panel where you spoke about your academic detailing project with dentists on opioid safety. Can you tell us a little more about how your team got started with this work? Adrienne: In 2018, the CDC released funds to states through the Overdose Data to Action (OD2A) grant and the state of Utah selected academic detailing as one of the interventions they wanted to use. AD is one of the many different modalities that we use within my organization to reach clinicians to educate them and have an impact on the kind of care they provide. The state began looking at specific regions and populations to target after we received the funding. Utah is unique in that it has a high number of adolescents undergoing surgery for wisdom teeth removal, which is one of the most common instances where controlled substances are prescribed. A first prescription can be a huge turning point to potentially becoming addicted to a substance, especially at a young age. That’s when we decided to put together a team of two detailers to detail dentists. I was lucky enough to attend each detailing visit and collect data through pre- and post-surveys and answer any administrative questions that came up.  Anna: It’s impressive that your organization was able to look at the data in your state and build a program to fill a specific care need. What makes dentists and their environments unique when it comes to detailing? Adrienne: There’s a theory that providers who are prescribing controlled substances are working within systems and teams that are well-poised to understand the challenges of opioid prescribing. Dentists fall into a different healthcare model that’s often siloed; they aren’t usually affiliated with an overarching health system or university like many primary care providers are. This results in isolation, making the interactive, 1:1 outreach model of detailing even more important – we knew we needed to bring the information and support directly to them in their dental offices. Anna: Detailing seems like a critical need for isolated dentists, both in providing them with customized education, but also in building connections. Were there any special considerations that your team took into account as you worked with the dentists? Adrienne: The language that’s used in the dental world is very different than language that’s used in primary care. We were fortunate enough to have a dental provider, who’s a champion of AD, work with us as a detailer on our project. He knew the language, understood the workflow, and could speak to the need for safe opioid prescribing. He always started his detailing sessions with a personal story like, “When I took wisdom teeth out, I would always prescribe 40 Percocet pills. All I can think of today is, ‘what have I done?’” You could see the mood shift the moment he started talking about his personal experiences, allowing for a connection between himself and the dentists he met. The success of this program wouldn’t have gone even half as far without his support.  Anna: A detailer who can build empathy with clinicians and who has personal experience with a challenging topic is an important asset to have in a detailing program. What obstacles did you face as your team implemented this project? Adrienne: Connecting with dental offices, in general, was tough. We first started by working with dental associations to get relationships in place. We submitted newsletter articles, attended meetings, presented at the regional conference, and sent our program’s information via their listservs. We also Googled practices and found ones that had more than one dentist working in the office at a time. We’d cold call those offices and say, “It looks like you have a big operation – is there a way we could bring training in for your team for continuing education credits?” Before leaving the visits, we’d ask the dentists for referrals to other clinicians and leave flyers behind. Relationships grew organically over time. Anna: It sounds like the project began to build on itself fairly quickly. Did your team experience any barriers from the dentists during the detailing visits? Adrienne: We had a lot of dentists who thought the opioid crisis wasn’t relevant to their practice and we knew that we had to find ways to tie it into their profession. Fortunately, dentists have historically been involved in public health movements because they hold a different type of relationship with patients that is closer than a typical relationship with a primary care provider. They see patients more frequently and can detect small changes in health quickly. The dental profession was incredibly important in the tobacco cessation movement in the 1990s. They were instrumental in getting individuals to reduce or completely stop using tobacco. Dentists are also starting to be trained in domestic violence and human trafficking. For the dentists who were hesitant about the relevance of our detailing visits, we would say, “You have this amazing relationship with patients that we don’t see in other parts of healthcare—here’s how you can make a huge difference!” or “I can understand how there would be a lot of fear to step out of your comfort zone; we have a lot of resources and materials to support you.”  Anna: Dentists truly have a unique relationship with patients that can be used to promote countless public health initiatives. Can you think of a time your team was able to empower a dentist to change behavior and encourage them to see their relevance in combatting the opioid crisis? Adrienne: There was a dental group in a rural part of the state that had one dentist and a big support staff. We came in for a detailing visit and had a conversation with the entire office. After the meeting, one of the dental assistants pulled me aside and told me that a patient who had recently completed substance use rehab had visited the office in need of a procedure that would warrant prescribing an opioid. No one in the office knew what to do for pain control and they were all unsure how to approach the patient given his history. She said that because we came, she felt like she now knew how to have a conversation with him about the procedure and his safer, alternative options for pain management. The dentist also shared that prior to our visit, he often didn’t know how to handle conversations about pain management and opioids and wasn’t sure if it was his job to do so. After our visit, he said he felt comfortable and confident doing this, and shared an anecdote of being able to create a safe space for an ongoing conversation with a recent patient. Anna: It seems like your team has had such an impact by using one of the core elements of detailing – building relationships through empathy, validation, and support. Can you share some encouragement for readers who are considering having these conversations with dentists? Adrienne: Be flexible and don’t come in with your own agenda – be sure to let the dentists drive the conversation and let them teach you along the way. It can be a rewarding yet challenging experience – don’t forget to celebrate the small wins on your journey! Anna: Thanks for sharing this innovative approach to detailing, Adrienne! We’re looking forward to hearing about your continued impact with the dental community and beyond. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Ms. Butterwick is a Senior Improvement Advisor at Comagine Health. She is currently working on quality improvement efforts directed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to improve quality of care for residents living in post-acute and long term care as well as assisted living and home health. She's also working on an initiative to increase advance care practices in those settings. In addition, through a subcontract with the Utah Department of Health, Ms. Butterwick currently provides educational support for opioid prescribing to family medicine and dental providers. Her work with this contract has earned national recognition and has been presented at the RX Drug and Heroin Abuse Summit in April 2020 and the American Public Health Association’s annual conference in October 2020. She is currently also collaborating with faculty from the University of Utah regarding telehealth and advance care planning initiatives through the Utah Geriatric Education Consortium and Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Programs. She completed her Bachelors of Science degree in Behavioral Science and Health at the University of Utah in 2007 and her Master's in Public Health at Westminster College in 2014. She has also earned recognition as a Certified Healthcare Education Specialist (CHES). In her 15 years of public health project management she has also worked in rural health research, provider education programs and care management. She has a strong passion for quality improvement and public health.  We’re featuring a snapshot from academic detailer, Carolyn Wilson, a Senior Health Program Coordinator at Ledge Light Health District. By Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD Tags: Substance Use, Detailing Visit  Anna: Hi Carolyn! Can you walk us through how you gain access to clinicians? Carolyn: Absolutely! When it comes to finding clinicians and getting them interested in our program, it’s really all about word of mouth. The clinicians quickly learn that the information I share is valuable and that I’m respectful of their time. I say things at the end of our visit like, “if you really enjoyed this session, the best compliment that I can receive is a referral to somebody else.” A referral or warm handoff always seems to work for me when gaining access. I also do a little bit of cold calling on LinkedIn - I share information about our program and attach our flyer. I make sure to mention our continuing education credits, referral gift cards, and swag. Clinicians absolutely love our insulated travel mugs. We’re fortunate enough to have the funding to provide these incentives through our grant. Once I’m 1:1 with a clinician, I always try to set the stage during our first meeting, especially if I don’t have a relationship with them. I let them know that I’m a non-clinical health educator and that I have a background in public health. I like to say that I’m a health promoter, not a clinician. I tell the clinician I’m working with that they know how to do their job, but I’m there to support them. I always thank them for their interest and time, which helps to build that relationship and open the door for follow up visits. Bottom line - entice people and let them know your value! At the end of the day, you want clinicians to know that you’re there to help them and that they can access you whenever they need support. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation! Biography. Carolyn Wilson is a health educator and prevention specialist serving as a program coordinator at Ledge Light Health District in New London CT for 11 years. Carolyn studied public health and health education at New York Medical College. Keenly interested in health promotion and behavioral science, Carolyn enjoys bringing her passions and talents to both primary prevention and academic detailing work. Carolyn has been serving as an academic detailer for over 2 years and enjoys speaking with clinicians about strategies to prevent opioid related deaths. Carolyn also manages the Groton Alliance for Substance abuse Prevention @Groton_Prevents. In her spare time, Carolyn enjoys serving on the Board of Directors for the CT Association of Prevention Professionals and Fiddleheads Food Cooperative. To connect with Carolyn, find her on LinkedIn.

An interview with Carolyn Wilson, a Senior Health Program Coordinator at Ledge Light Health District. Ledge Light Health District is located in New London, Connecticut and is the regional health district serving the southern part of New London County. by Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD Tags: Opioid Safety, Evidence Based Medicine, Substance Use  Ledge Light Healthwatch Ledge Light Healthwatch Anna: Carolyn, we’re thrilled to feature you on our DETAILS blog! I know you wear many hats – can you tell us about your current job role? Carolyn: I’m a health educator working within primary prevention, an academic detailer, and the host of our health district’s television program called Healthwatch. Healthwatch covers topics like mental health, physical health, disaster preparedness, general public health, COVID-19, environmental health, and disease prevention. I’ve been with Ledge Light Health District for 11 years. Anna: It seems like improving patient and community health outcomes is a common thread across all your roles. What primary prevention work or related projects complement your AD work? Carolyn: Depending on what topic I'm detailing on, I lean into my primary prevention work or the harm reduction work that my colleagues are working on. One of the larger initiatives I often share with clinicians during detailing visits is the Naloxone and Overdose Response App (NORA) project. The Department of Public Health developed a web-based application that can be downloaded directly to your phone. It has information about preventing, treating, and reporting opioid overdose. The app can be used by both folks in the community and clinicians. I also speak to clinicians about proper medication storage and disposal while promoting our “Take it To The Box” Initiative.  Anna: We love to see programs using AD to spread the word about broader, community-focused initiatives. Are there other ways that your opioid-related AD work overlaps with work being done within your department? Carolyn: Yes! I’m so lucky to be able to work in the office side-by-side a recovery navigator. She helps link folks in the community to addiction services. Every day we say things like, “hey, I overheard you talking to that pharmacist just now – do they know x clinician?” We often share resources and try to work together to ensure that community health goals are achieved, often by making sure that the work people are doing is connected rather than existing within silos. It all comes down to helping one another work towards a common goal. Anna: What better way to work towards a common goal than to share resources across colleagues and projects! Can you share a story from the field where there was an intersection among various projects?  Carolyn: I detail a lot of advanced practice nurses (APRNs) and also work with them on some of my primary prevention projects. The overlap in projects helps me build strong relationships with these clinicians. I sometimes work with school-based health centers as part of my prevention work, and these health centers are typically run by APRNs. These centers act as an access point to care for many students and families. It’s essentially a primary care clinic right in the school. The Child and Family Agency oversees the school-based health centers in southeastern Connecticut and reached out to me after a horrific event in a Connecticut middle school. A few months ago, a 12-year-old got access to fentanyl and brought it to school. He overdosed and passed away a few days later at the hospital. We haven’t seen many overdoses in schools, but after this happened, a lot of schools started looking at their policies and school-based health centers wanted to have naloxone on hand. The medical director of the Child and Family Agency advocated for a policy that required all school-based health centers to have naloxone and to be trained in administering it. Anna: What a devastating story. Have the school-based health centers been able to put these types of new policies into place? Carolyn: When one of the clinicians from the Child and Family Agency reached out to me, she said, “Carolyn, I know you do this kind of work. You trained me in naloxone not too long ago during an academic detailing visit. I’d like to have a naloxone training for my nurse practitioners in the school-based health centers. I want naloxone available in all of our clinics.” This type of request would typically be delegated to somebody else in our department, but because of the relationships I had built through academic detailing, I was asked to provide the training, and I did. As a result, the school-based health centers now all have access to naloxone and the clinicians know how to administer it.  Anna: It’s incredible that you’d built trusting relationships with clinicians enough to be asked to provide this training, contributing to changing a policy in a span of one or two months. Carolyn: It means a lot that they came to me because they trusted me and knew I could get it done for them. I truly don't think I would have been involved if it wasn’t for my academic detailing work. Anna: I agree. It’s been a pleasure learning about your work and your unique approach to academic detailing. We’re excited to follow along with you on your AD journey as you continue to promote health across your community. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Carolyn Wilson is a health educator and prevention specialist serving as a program coordinator at Ledge Light Health District in New London CT for 11 years. Carolyn studied public health and health education at New York Medical College. Keenly interested in health promotion and behavioral science, Carolyn enjoys bringing her passions and talents to both primary prevention and academic detailing work. Carolyn has been serving as an academic detailer for over 2 years and enjoys speaking with clinicians about strategies to prevent opioid related deaths. Carolyn also manages the Groton Alliance for Substance abuse Prevention @Groton_Prevents. In her spare time, Carolyn enjoys serving on the Board of Directors for the CT Association of Prevention Professionals and Fiddleheads Food Cooperative. To connect with Carolyn, find her on LinkedIn.  We’re featuring a snapshot from an academic detailing visit with Corinne Puchalla, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacist and academic detailer at Illinois ADVANCE. By Anna Morgan, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD Tags: Substance Use, Detailing Visit  Hi Corinne! Can you tell us about a recent academic detailing visit that you’re proud of? Academic detailing does not come naturally to me—each visit starts with excitement, nervous energy, and the tingling anticipation of the unknown: Will the prescriber be in a good mood and be receptive to the key messages? Will I be able to express myself adequately? Will I negotiate the right “ask”? NaRCAD’s training elevated my confidence in making “the ask.” I’ve learned how to set small, quantifiable goals and give the prescriber a short timeframe for follow-up. My first academic detailing visit after the NaRCAD training had the potential to be a doozy. The topic for discussion was the CDC guidelines for chronic pain management, and I was scheduled to meet with someone who only dealt with acute pain management in cardiothoracic surgery.  Adding to my sense of foreboding was the knowledge that the prescriber had been singled out by her employer for this AD visit based on the number of opioid prescriptions she’d written. Using the communication strategies I learned at NaRCAD, I researched and prepared more for this visit than I had for any other. I practiced with multiple colleagues. On the day of my visit, I felt ready—but uncertain. My practice paid off. What began as a terse, somewhat tense conversation with the prescriber turned into an educational, productive, and collegial visit. I used my AD communication skills to dovetail from one question into another, ultimately discovering how my key messages resonated with the prescriber. I’m proud of the strides I made during that AD visit. I remained calm despite my anxiety, used my research on acute pain management to ask open-ended questions, translated what I know about chronic pain to support her in the acute pain setting, and laid the foundation for a strong, collaborative relationship. Best of all, I made a solid “ask.” I’m motivated to do it all over again with my next prescriber and take each learning opportunity as it comes. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation! Biography. Corinne is a clinical pharmacist at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) College of Pharmacy. She uses her passion for drug information and advancing patient care in her role as a clinical instructor and academic detailer. Her areas of interest include hepatitis C, migraine, and diabetes pharmacotherapy, and new drug approvals. Corinne is a proud graduate of the UIC College of Pharmacy, Class of 2016. Her enthusiasm for science, health, and helping others prompted her to pursue a career in pharmacy. Before beginning her career in pharmacy, Corinne was a symphonic bassoonist and also worked as personnel manager for The Florida Orchestra. She graduated from the University of Iowa with a Bachelor of Music in 2001 and from Indiana University with a Masters in Music in 2006.

Academic Detailing to Address Substance Use in New Jersey: An “All-Hands-on-Deck” Approach11/30/2021

An interview with Clement Chen, PharmD, BCPS, Clinical Pharmacist Specialist, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. by Anna Morgan, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD Tags: Substance Use, Detailing Visits, Evidence Based Medicine  Anna: Hi Clement! We can’t wait to hear about all the impactful work you’ve been doing in New Jersey. Tell us a little about your academic detailing program. Clement: The Northern New Jersey Medication-Assisted Treatment Center of Excellence was established in 2019 and is funded by the New Jersey Department of Human Services. Our goal is to not only increase access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) in office-based addiction treatment practices, but also to ensure that providers treat this chronic disease with evidence-based practices. Our vision is to end the stigma of addiction and ensure that all people with substance use disorders have access to high quality care so they may live full and satisfied lives. I was hired as the academic detailer to provide education and identify the needs of providers in these practices. Anna: Tell me more about the types of providers you visit. Clement: I’ve been working with providers from all areas of care. In addition to office-based providers, they also include those from hospital settings, psychiatric hospitals, community health centers, substance use licensed facilities, and prison settings. Addressing the substance use crisis requires an “all-hands-on-deck” approach. Any setting where patients seek care are environments where detailing can improve patient access to support. Anna: It’s so important to approach academic detailing with a wider lens and consider where it can fit in with other community initiatives. Can you walk us through some of the work you’ve done so far, or are planning to do, in each of these settings? Clement: I’d be happy to!  Hospital Setting: One of the inner-city hospitals that we are working with is looking to establish an addiction medicine service within their hospital system. The goal is to provide trainings and consultations on best practices for addiction medicine, in addition to technical assistance in setting up a program. I’ll be working with their attending physicians and residents to provide evidence-based practice trainings. Another one of our partners, an addiction medicine provider, has been pushing for greater initiation of MOUD in her own hospital system. The main issue is to ensure that providers use MOUD in an evidence-based manner and adhere to the latest findings. For example, the provider has been receiving pushback from other providers due to the lack of referral sources. These providers have shared that they believe MOUD should not be initiated without a “warm handoff.” Furthermore, buprenorphine has been discontinued during the pre and peri-operative settings and only resumed post-operatively despite growing evidence for continuing buprenorphine in these settings. I plan to detail these providers in-person to provide literature supporting the use of MOUD, even when warm handoffs are unavailable. I’ve provided supporting literature and a summary to the addiction medicine provider to assist with her case to expand this initiative, which helped her to develop an information sheet to justify the expansion of MOUD in her hospital. Psychiatric Hospital Setting: We’ve also partnered with physician champions at some of the psychiatric hospitals in New Jersey. Stigma and the inaccurate idea that patients do not experience acute withdrawal for opioid use has made many providers hesitant to start therapy with buprenorphine. Psychiatric hospitals have been fervently looking to provide treatment for opioid use disorders. The goal is to implement a clinic designed for initiating and maintaining those on buprenorphine and naltrexone extended release. We’ll be assisting with the implementation of the clinic and provide individual in-person detailing visits for the providers at the hospital. To prepare for this, we’ve developed several informational sheets on MOUD and other related information to give to the providers.  Community Health Center Setting: One of the community health centers that we’ve partnered with wants to begin providing MOUD for those already on the therapy. There are several advanced nurse practitioners and physicians at the health centers looking for more guidance and support on the appropriate prescribing of buprenorphine. I’ll be working with their team to provide them with evidence-based practices and help them with buprenorphine induction strategies. Substance Use Licensed Facility Setting: One of the substance use licensed facilities I’ve consulted with mentioned that fentanyl has made initiation of buprenorphine very difficult due to the increase in the number of cases with precipitated withdrawal. As a detailer, I’ve worked closely with their lead providers, providing them with available literature on alternative buprenorphine induction strategies. They're in the process of updating their protocols for the induction of buprenorphine. Another facility is working with us to start prescribing MOUD within their residential settings. Prison Setting: I regularly consult with the Department of Corrections providers since access to MOUD have traditionally been low in the prison system. Their patients also have unique needs compared to those in the community setting. I meet with them on a monthly basis via a case conference and discuss clinical solutions in order to help them provide the best care to their patients.  Anna: Your work is incredibly comprehensive and thoughtful. It’s truly amazing to see how your team has incorporated academic detailing into so many initiatives and clinical settings within your community. Clement: We believe that to overcome this crisis, all patients with opioid use disorder need equitable and timely access to care. With the record number of overdose deaths reaching over 100,000 in one year, this is our greatest focus. We’re confident that our academic detailing work will help us achieve this goal. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Dr. Clement Chen graduated from the Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy at Rutgers University in 2013 with his Pharm.D. He then completed a one-year residency at the Hudson Valley Veterans Affairs Ambulatory Care Clinic. Thereafter, he has worked as a staff pharmacist at St. Michael’s Medical Center in Newark and as a cardiology heart failure clinical pharmacist specialist at University Hospital in Newark. In addition to working as a clinical pharmacist specialist, he was a Transitions of Care pharmacist at Hunterdon Medical Center from 2016-2020. This has helped him to balance his inpatient and outpatient roles as a pharmacist. To further demonstrate proficiency in clinical pharmacy care, he received his Board Certification in Pharmacotherapy in July of 2016. His current role is as the academic detailer in the Northern NJ Center of Excellence, with the goal of providing education and support to increase statewide capacity to provide medications for addictions treatment (MAT) for patients with substance use disorders with a focus on opioid use disorder.  We’re featuring a snapshot from an academic detailing visit with Reem El-ankar, MPH, an academic detailer and health educator at the Florida Department of Health in Broward County. by Anna Morgan, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD Tags: Substance Use, Stigma, Detailing Visits  Hi Reem! Can you tell us about a time that you felt like you made an impact during an academic detailing visit? I’ve experienced countless rewarding moments as an academic detailer working to educate healthcare providers. One particular visit instilled a strong sense of satisfaction and pride in me. I was detailing a primary care clinician who manages several chronically ill patients. He was aware of the CDC guidelines and statistics on the opioid crisis. Because the clinician was well-versed in this area, it was challenging to serve as an educator. I walked through the key messages with him, and we made progress. We hit a roadblock when we started discussing the topic of co-prescribing naloxone with opioids. He expressed a concern that co-prescribing naloxone could encourage patient overuse of prescription opioids; he believed that naloxone should only be used as a safety net for individuals diagnosed with substance use disorder.  I reviewed the evidence with him, showing him that co-prescribing naloxone can save lives for all patients using opioids. After I provided the CDC data and studies that describe the benefits of co-prescribing naloxone, the clinician was more receptive to the information I was presenting. At the conclusion of the detailing visit, I reminded him that saving one life with naloxone was worth the effort, and that his primary mission is to save lives. After that he smiled and said, “Okay, you got me.” I asked him if he could commit to co-prescribing naloxone to just one patient, and his response was, “Due to your clear passion for this national crisis, I will prescribe much more than just one.” This experience taught me that my passion coupled with data and statistics has the potential to impact lives. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation! Biography. Reem El-ankar is an academic detailer, health and community educator, and public health professional. She holds a bachelor’s degree in pharmaceutical science from the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, and a master’s degree in the public health from Purdue University Global - Indiana, US.

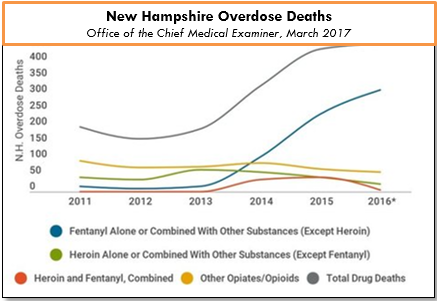

Before joining the department of health, she worked in the private and the non -profit sectors as a pharmaceutical representative (Kuwait), and a community outreach and a HRSA grant coordinator, respectively. During her internships with the American Red Cross and the local department of emergency managements, she worked in community preparedness and emergency response field on the national and international levels. An interview with Julia Bareham, BSP, MSc, Information Support Pharmacist, Academic Detailer, RxFiles Academic Detailing, College of Pharmacy and Nutrition, University of Saskatchewan. by Anna Morgan, MPH, RN, PMP, NaRCAD Program Manager Tags: Substance Use, Stigma, Detailing Visits  Anna: Hi Julia! We’re so excited to feature your work on DETAILS. You’ve had over a decade of experience with academic detailing. Can you tell us about your academic detailing journey? Julia: I was hired by RxFiles in 2009. Shortly after starting with RxFiles, the program began working on a long-term care project and that became my focus until I left in 2015 to work in the prescription monitoring program in my province in Canada. I returned to RxFiles in 2019 and have since been working on helping to increase Suboxone prescribers in Saskatchewan. Anna: It’s nice to have you back in our detailing community! What are some of the unique challenges that you’ve faced since returning to the field and detailing on this particular topic?  Julia: I think the most obvious answer is the global pandemic, which is a challenge that everyone has faced. For me, building relationships with clinicians through videoconferencing has not been easy. Reading your audience via videoconferencing is challenging, and that’s if you're fortunate enough that they'll have their cameras on! In terms of the topic itself, many prescribers are unfamiliar with prescribing Suboxone and there is still some stigma related to opioid use disorder. Presenting the appropriate information to prescribers to properly assess, treat, and troubleshoot is key. Prescribers also must be authorized by their regulatory body to prescribe Suboxone in our province, which includes an educational program and mentorship. To help make prescribing Suboxone less overwhelming, we created a Suboxone 101 resource for our detailing visits where we introduce clinicians to the treatment option and some of the main considerations around it. We also created a longer resource that walks through a detailed approach of assessing patients and prescribing Suboxone if clinicians indicate that they want to learn more. We’ve received positive feedback on our 101 resource and have had a lot of interest in our longer resource, which we plan to detail interested clinicians on in the near future. Anna: Thanks for catching us up on some of the ways your program has approached detailing on this topic. Let’s talk a bit about being a detailer – what are some of your tips for being a successful detailer? Julia: That’s a great question.

Anna: These tips can be applied to work beyond detailing as well! How has your team supported you in using those skills and qualities to become such a successful detailer? Julia: I have an amazing team; we all have unique personalities and different approaches to detailing. They give me insights into how I might want to approach a certain topic when I’m in the field. I always gain new perspectives through trainings with my team, observing detailing visits, and debriefing after visits. It’s especially nice to be able to debrief with colleagues when things don’t go as planned during a detailing visit. Sometimes the debriefs are long discussions and sometimes they are a quick text message to share what happened. Our team is honest and vulnerable with one another, which helps elevate the work that we do because we can support each other during challenging times. We share wins with one another during debrief sessions as well. There's nothing better than a visit when you feel like you did an awesome job and really helped the clinician you detailed. It’s important to put that wind back in your sails! Anna: Speaking of wins, can you share a story from the field when you felt that you made an impact as a detailer?  Julia: Absolutely. When I first started detailing, I detailed clinicians at a neighboring clinic to the pharmacy I worked at. One of the first topics I detailed on was gout and we had a key message around selecting the best non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to use for treatment. I found that most of the prescribers I detailed were prescribing a less than optimal NSAID when it came to an acute gout flare. When I was later chatting with one of the clinicians at my pharmacy about a prescription that he had written, he said at the end of the conversation, “Oh, by the way, I just want you to know, I have changed how I prescribe for gout after meeting with you.” In that moment, it was clear to me that he wanted me to know that he listened to the evidence that I had shared with him and had changed his practice as a result. I knew that prescribing different NSAIDs for gout was probably not going to save lives but knowing that the clinicians were listening and valued what I had to share with them let me see that I could have an impact on them. Anna: That sounds like it was a nice boost of confidence for you as a new detailer. We’ll wrap up with our final question. Is there a piece of advice that you would offer to new detailers? Julia: For your work to be fulfilling and for you to have that sense of satisfaction, it needs to be meaningful. We want to know that the work that we do matters and that we're making a difference. I find that it can be hard to see that right away with academic detailing. Sometimes I might just be confirming that a clinician’s current practice is still the optimal approach and other times I might be causing a clinician to reassess how they might make future drug therapy decisions. Don't underestimate the impact you might be having on a clinician, and consequently patient care, in doing the work that you do. Anna: Thanks for sharing your perspectives, Julia! We look forward to hearing more about your impact in the future. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Julia joined the RxFiles team in 2009 and until 2015 she provided academic detailing services across the province of Saskatchewan, primarily focusing on medication optimization in the long-term care population. During that time, Julia also returned to the University of Saskatchewan to pursue her Master of Science degree in the division of Pharmacy focusing on comprehensive medication management, graduating in 2014. In late 2015, Julia joined the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Saskatchewan where she held the position of Pharmacist Manager for the Prescription Review Program. In early 2019, Julia returned to RxFiles and is currently focused on opioid use disorder, in addition to medication therapy in both geriatrics and psychiatry. An interview with Liesa Jenkins, MA, the Executive Director of ONE Tennessee, an organization devoted to addressing the opioid overdose epidemic statewide. by Winnie Ho, Program Coordinator Tags: COVID 19, Detailing Visits, Opioid Safety, Program Management, Rural AD Programs, Substance Use  Winnie: Liesa, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us today about your experiences at the helm of ONE Tennessee through the past year. Can you tell us a little bit more about yourself and the AD-related work that you do? Liesa: As the Executive Director of ONE Tennessee, I have overall responsibilities that include strategic planning, funding, communication, and staffing in addition to coordinating our AD program. I’m responsible for recruiting, training, and supporting our detailers to be as effective as possible. Our mission is to combat opioid misuse and overdose, and AD is just one of many projects and strategies we have to do that. W: You certainly wear many hats in your leadership role! Can you tell us about the experiences that have shaped how you approach leadership?  L: There were a very diverse set of experiences that influence how I’ve learned to lead. It’s also important to recognize that leadership comes in all forms. I was a foreign language teacher for 10 years, I had to learn the many different ways of communicating information to students from young teens to older adults. You learn to consider the way you present your information to help get all of your students to their goals. I was also a director of a non-profit and managed volunteers. Just like my students, you quickly learn that people have many different motivations. A good leader knows how to cater to those motivations and learns how to maximize the team they’re working with. It’s also important to always remember to express gratitude towards your team, and as often as possible, remind them of the impact that they’re making. W: You’ve discussed a lot of the soft skills and characteristics that good leaders have. What about some of the technical abilities that helped you be successful at managing an AD program?  L: Before coming to ONE Tennessee, I worked at both the federal and state-level in healthcare-related consulting work. It gave me exposure to federal and state-level funding procedures, as well as the decision-making process that goes on behind the scenes. You also learn about the regulations and guidelines that AD helps to keep clinicians aware of. W: It sounds like you’ve had a fantastic journey on your way to the position that you have now in leading an AD initiative. Can you tell us a little bit more about the different community organizations that support ONE Tennessee’s AD work? L: We have support from multiple organizations including the Tennessee Pharmacists Association, the Tennessee Hospital Association, and the Tennessee Primary Care Association. They’ve helped us recruit clinicians to serve as detailers and to participate in detailing sessions. We also have support from the East Tennessee State University’s College of Public Health and the Tennessee Department of Health supporting our data collection and program evaluation. We are thankful to other provider organizations including local community pharmacists and clinicians at Alliance Healthcare Services to assist us in development and distribution of materials  W: That’s quite a dynamic bunch! At the intersection of many different groups in the community all focused on preventing opioid-related overdose, how do you keep all these different stakeholders on the same page? L: Even when you speak the same common language, not everything is always communicated and understood as intended. I work with a talented team from diverse career backgrounds, including finance, legal, communications, and policy professionals. They don’t all speak the same exact “language” because of their professional backgrounds. The role I often play in group meetings is that of a facilitator. I'm comfortable asking the so-called “dumb questions” or constantly asking for explanations. As a leader, it’s my job to make sure there is clear understanding among the folks in the room who don’t work in that field. It’s important as a leader to not only communicate well, but to also make sure everyone on your team is communicating well enough so that everyone can understand and also be understood.  W: Intentional level setting is a hallmark of effective leadership and communication. It allows meetings and decisions to be productive, and it ensures that everyone’s goals are aligned. Otherwise, important details may get left behind or not fully developed. L: Exactly. It’s also important to know that with your team, you’re never alone. You don’t need to know everything to be a leader, but you need to surround yourself with people who can collectively make decisions based on good information. Surround yourself with people who know more than you do, and listen to them. W: You picked up this role in the middle of a pandemic and with your leadership, we were able to launch our first virtual training pilot with ONE Tennessee for about two dozen detailers. It was a huge undertaking! What would your advice be for someone who’s looking to tackle big projects in their role as the leader of an AD organization?  L: I would say first and foremost – the determination to fulfill our commitments was important to me. I knew what was in our contractual agreement with our funders, and didn’t want to start off our organization with a fail in this category! Secondly, create a timeline with the concrete things that need to be finished and the resources you need to help you monitor progress along the way. Finally, in the face of making new things happen – it can be daunting when there’s a big mission to accomplish. When there’s nothing on the drawing board yet, a leader is someone who volunteers to put up the first “strawman” plan. It doesn’t need to be perfect, but it gives everyone something to build off of; it’s always better to start with something, like the first brick in the foundation. W: We’ve talked a lot about how to bring a community together to support an AD intervention. Why is community involvement important to the success of an AD intervention?  L: Well, whether you’re talking about opioids or HIV or chronic illnesses, the reality is that no one individual or organization within a community can solve a public health problem alone. Even though AD is mostly about the relationship between the detailer and the clinicians they work with, it’s informed by many other people who care about improving health outcomes. In short, the program would not be able to operate without the leadership and support of these partners! In a state as large as Tennessee, with such wide differences among rural and urban, from the Appalachian region to the Mississippi Delta, racially diverse but largely homogeneous in some places, it is important that collaboration occur at local levels as well as at state levels—both among clinical colleagues in the same community who care for the same patients, and also with support from state-level organizations who can leverage resources that may not be available in the local community. While individuals and organizations may not agree on all points, it is usually possible to find at least one shared goal that can be worked on together. As an organization, we strive to identify and then mobilize to address those common goals. There are great things ahead for us all if we continue to work together. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  In her current role as Executive Director of ONE Tennessee, Liesa draws upon her experience as an educator, a non-profit administrator, a state-level director of community health programs and a consultant to state and federal officials, as she works to advance the organization's mission to combat the opioid epidemic through collaboration and sharing of information among health professionals and communities in Tennessee. In her professional roles at Kingsport Tomorrow, CareSpark, Deloitte Consulting and the Tennessee Department of Health, Liesa has helped to develop and implement a broad range of collaborative projects at local, regional, state and national levels to improve community health, broadband access, education and literacy, employment opportunities, cultural arts exchanges, global trade, environmental protection, neighborhood revitalization, youth development and civic leadership. Her skills in strategic planning, resource development, mentoring and community organizing have been recognized with awards, including being named a Paul Harris Fellow by Rotary International, a Health Care Hero by the Business Journal of Tri-Cities, and the Commissioner's Award of Excellence from the Tennessee Department of Health. Liesa received her B.A. in French from King University in Bristol, Tennessee and her M.A. from the University of Kentucky in Lexington, Kentucky. She also holds a Certificate of University Studies from the Université de Franche-Comté in Besançon, France, and is certified as a Project Management Professional by the Project Management Institute. Liesa is a native of Glade Spring, Virginia, where she is a seventh-generation resident on her family's farm, and enjoys spending time with her three sons and their families, as well as quilting, reading, and traveling. An interview with Jacqueline Myers, BSP, Academic Detailer, RxFiles and Pharmacist, Infectious Diseases Clinic, Saskatchewan Health Authority – Regina Area. RxFiles is an academic detailing program that provides objective, comparative drug information to clinicians. Jackie’s work at RxFiles includes academic detailing and resource development. by Anna Morgan, MPH, RN, PMP, NaRCAD Program Manager Tags: COVID 19, Conference, Detailing Visits, Substance Use  Anna: Hi Jackie! We’re excited to feature your work as a detailer. How did you first become involved in academic detailing? Jackie: RxFiles has a bit of a celebrity following in Saskatchewan. The RxFiles books, which are packed with resources and drug comparison charts covering various clinical topics, are a coveted possession. You receive one book for free as a pharmacy student and everyone looks forward to that day because it has all the study material you could ever need in one place! I think it’s a dream of pharmacy students to get involved with RxFiles at some point in their career. I started with RxFiles in 2019 while working within the Saskatchewan Health Authority (SHA) Opioid Stewardship Program (OSP). A partnership was formed between the OSP and RxFiles and I was able to work both as a clinician at the Regina Chronic Pain Clinic and as a detailer providing education and creating content for RxFiles. My role in SHA has since changed, but I’ve continued detailing for the RxFiles team.  Anna: Your passion for academic detailing is palpable. You could tell how much you love academic detailing during your presentation at NaRCAD2020. Can you tell us a little bit more about why this work is so important to you? Jackie: It excites me to hear that--I’m so glad people see that I’m passionate about this. I’ve always admired musicians and artists for their passion, but I’ve never pictured myself as one of those people. Many healthcare professionals - nurses, pharmacists, physicians, physiotherapists – we all go into this field because we like or love working with people. I’m no different than any other healthcare professional. I also really love to learn and then share that knowledge through teaching or mentoring. Academic detailing is such a cool combination of those things. You get to learn about a specific clinical topic, share your knowledge with another clinician and ultimately improve patient outcomes. It’s a really special process. Anna: You’re absolutely right – it is special! What kind of support has been most helpful for you in becoming such a successful and passionate detailer? Jackie: When I first started with RxFiles, the rest of the team was working on topics other than opioid prescribing which left me feeling a bit isolated. Luckily, RxFiles has a great support system. My colleague Debbie, who I now consider my mentor, has been a huge resource for me. Even though we weren’t detailing on the same topic, I knew I could always talk through key messages with her, as well as recruitment strategies and other tips for approaching prescribers in our area. I still know that I can always go to her for a debrief at the end of a visit, whether it’s a successful visit or a mess of a visit. Academic detailing has the potential to be really isolating, so having someone who understands and can help guide you through some of your challenges can be so beneficial.  Anna: We know that academic detailing can be isolating, so it’s wonderful to hear how supportive your team is. On the days when you’ve had hard visits, I’m sure it’s difficult to feel that you’ve made an impact. How do you know that you’ve been successful in a detailing visit? Jackie: At the 2019 NaRCAD Conference, I was amazed by the presentations and the data that different programs had collected to measure impact. When I first started detailing, I was very focused on the clinician I was detailing committing to make a change or doing something differently in their practice. Then I began to learn that success in academic detailing comes in two forms. One is making an impact that changes a clinician’s practice and the second is establishing a connection and developing a relationship with a clinician. Sometimes making a connection will come first and then lead to making an impact, or sometimes they’ll occur simultaneously. Those are the two ways that I define success for myself in academic detailing. Anna: That’s spot on – those are two of the main goals of academic detailing. Can you share any success stories from the field from a time when you felt you made an impact?  Jackie: Of course! We are currently working on a special project to increase the number of buprenorphine/naloxone, or Suboxone, authorized prescribers in our province. One of the physicians I detailed was not yet authorized to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone. He was a hospital physician and worked in internal medicine. He shared with me that he’d been thinking about becoming authorized and was apprehensive, but he saw a need for it in his patient population. A lot of his patients were being admitted for various diagnoses but would also have a concurrent substance use disorder that went unmanaged or ignored. After our detailing session, he reached out to me. He described a patient that he had admitted for an infectious process who also had opioid use disorder. He said, “before our conversation, I would have normally treated the infection and probably ignored the opioid use disorder. It’s possible the patient may have left against medical advice, and I would have thought, ‘that was their choice, and I did my best.’ ” After our detailing visit, he felt that he had the courage and the skills to discuss the patient’s opioid use disorder with them and think about what he could do as a physician to keep the patient comfortable and safe while they were in hospital. This honest conversation led the physician to speak with an authorized prescriber who was able to initiate the patient on buprenorphine/naloxone while they were admitted in the hospital. Even though the ask for this detailing project was to increase authorized prescribers, which he has not yet become, the interaction I had with this physician still led to a positive patient outcome and a better patient experience. Anna: Thank you for sharing that - it’s so nice to hear stories from the field. Even if you don’t accomplish the messaging you were sent out to do, you’re still making an impact. Can you share a story where maybe you weren’t as successful and how were you able to bounce back from a situation that was challenging for you?  Jackie: During COVID, a physician reached out to request a virtual visit. We started our detailing session and I was beginning my needs assessment. I started asking about his practice and his familiarity with buprenorphine/naloxone. He said, “that’s a new weight loss drug, right?” From that point on, he was really sad that I wasn’t there to talk about a weight-loss drug. He was disinterested and I could tell he was distracted. I could hear him moving around papers through the phone and I could hear people talking in the background. I said, “if this is not a great time for you, we can definitely rebook” but he insisted that I continue. I could feel myself getting frustrated, but I finished the visit. I was able to deliver my key messages, but I left the visit not feeling great. There was no commitment to action or change and we didn’t build a connection. I felt like I wasted both of our time. In order to bounce back from something like that, I think you need to acknowledge that it will happen sometimes and debrief with colleagues who have been in your shoes. Then just pick yourself up and try again. Anna: That’s great advice. It can be discouraging to have a visit like that, especially if your new in the field! One last question to wrap up - do you have any personal academic detailing goals for this upcoming year? Jackie: Yes! I was previously detailing on only opioid-related topics. This year, my role has changed a bit and I will be detailing on various clinical topics and in a new geographical area with all new clinicians. My primary goal is to connect and build relationships with these new clinicians. Fortunately, I’m taking over for a cherished detailer who is retiring and will help provide a warm handoff. My secondary goal, which is a bit sillier, is to avoid troubles on the highway when we begin in-person visits again. The detailer I’m taking over for has had some very interesting car trouble heading out to his detailing visits. He’s met a lot of wildlife and his car was even once fried by lightning! Anna: We certainly hope you’re able to avoid those highway issues! Thanks so much for chatting with us today, Jackie. Your stories are inspiring, and we can’t wait to connect again and hear about all your 2021 accomplishments. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Jackie graduated from the University of Saskatchewan with her Bachelor of Science in Pharmacy in 2012. She has practiced in numerous clinical settings including community pharmacy, long term care, and hospital in the areas of internal medicine and opioid stewardship. Jackie is currently involved in the management of people living with HIV and substance use disorders at the Infectious Diseases Clinic in Regina. She also works with RxFiles providing academic detailing services and resource development. This interview features Carla Foster, MPH, who leads the conceptualization, implementation, and evaluation of Public Health Detailing as an Epidemiologist within the Bureau of Alcohol and Drug Use Prevention, Care and Treatment (BADUPCT) at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH). She is currently activated for the COVID-19 emergency response as Lead Analyst managing the Reporting Unit within the Integrated Data Team of DOHMH’s Incident Command System. By Winnie Ho, Program Coordinator Tags: Data, Detailing Visits, Evidence-Based Medicine, Health Disparities, Program Management, Stigma, Substance Use, Training  Winnie: Hi Carla! You’ve certainly had a lot on your plate with so many diverse campaigns. Can you walk us through the conceptualization process for your detailing campaigns, and how your team came to choose cocaine use as your current detailing topic? Carla: We can start with some data on this. In 2018, more New Yorkers died from drug overdose than from homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle crashes combined. Cocaine – in both crack and powder forms – has played an increasingly prominent role in this crisis. The mortality rate from overdose deaths involving cocaine more than doubled between 2014 to 2018, amounting to 52% of all drug overdose deaths in NYC. Some of the associated risks are serious - increased exposure risk to fentanyl, cardiovascular disease events and death.  W: That’s stunning data. Especially in the midst of the opioid crisis, it’s important that we don’t lose sight of other substance use issues going on right now. I’d love to learn a little more about the challenges and lessons that your team has learned by detailing on cocaine use. C: First, we have to be aware that fentanyl, a powerful opioid 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine may be found in many substances, including cocaine. We’re very concerned about fentanyl and cocaine because people who use cocaine do not have tolerance to opioids and are at even higher risk for overdose. It’s also important to address the perception of who is most impacted by high mortality rates. There’s this idea that cocaine use is more prominent in younger populations, but our data show that it’s actually impacting an older population more than many might expect. In particular, residents age 55-84 in the Bronx Borough have experienced the largest increase in cocaine overdose death rates in New York City from 2014 to 2018.  That’s why it’s critical for us to raise awareness in an effort to mitigate misconceptions and stigma around risky use and those who may have a substance use disorder (SUD). In addition to shame, there are still very real potential socioeconomic and legal consequences from disclosing substance use, which can deter folks from even seeking help. We take into account the unjust consequences of policies applied unevenly according to race, and how this impacts implicit biases in terms of which patients are thought to use substances, which types of substances they might use and even more critically, which type of treatment, if any, they are offered. Implicit biases combine with the effects of systemic racism to compound these consequences. It’s important to note that it’s not race that drives poor health outcomes, but racism.  W: Challenging stigma is one of the most powerful ways that detailing campaigns can combat the damage done by the War on Drugs, because stigma can make the difference of whether or not people receive dignified care. With a campaign so focused on addressing stigma and with a topic this important, how do you prepare your detailers for this task? C: We devote a significant amount of time towards training our detailing reps – a week-long training, 8 hours a day. We spend a large amount of that time talking in detail about stigma as related to cocaine use. It’s critical to us that our detailers are comfortable and knowledgeable when speaking about this topic, because it sets the tone for the providers who then set the tone for their patients. We ensure that our representatives are prepared to respond to a wide range of questions or comments, because this builds the provider-detailer relationship and enhances the value of the detailing visit. We’ve found during our follow-up visits that this support has led to high provider engagement with the campaign and providers reporting incorporation of the key recommendations into their daily practice, which is the aim of our public health detailing campaigns.  W: How have providers responded when detailed on a topic that carries so much stigma? C: The good news is that we’ve found NYC healthcare providers to not only be receptive to our work on substance use, but they’re eager to partner with us to support their patients once they learn about the severity of the issue. Our team provides statistics that relate to the provider’s specific neighborhoods and specialty, giving them real-time pictures of what’s happening with the patients they see. We know that it’s still a difficult topic to bring up, so we help address this with our action kit resources on stigmatic language and counter-top brochures that signal to patients that the provider’s office is a safe place to discuss these issues.  W: It gives me tremendous hope to hear about that there’s been enthusiastic response from providers. It means that things are changing. Let’s also talk a bit about program sustainability. Your team has worked extensively on campaigns across multiple topics. What have you learned from implementing past campaigns? C: Each public health detailing campaign is different, but we’ve learned some key strategies that support the growth and success of subsequent campaigns: