|

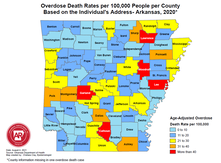

Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD Tags: Opioid Safety, Harm Reduction  The NaRCAD team is back on the road! We had the privilege of attending the 2023 Rx and Illicit Drug Summit in Atlanta, Georgia, where we joined a diverse learning community of over 3,000 participants. We heard about best practices in prevention, treatment, and recovery for those affected by the opioid epidemic and engaged with experts from various fields who have developed innovative strategies to combat the crisis. We attended presentations, poster sessions, and booths from a wide range of professionals, including clinicians, law enforcement personnel, public health officials, lawmakers, attorneys, families, and individuals in recovery. It’s clear that we need to continue to work together across disciplines to reduce opioid use disorder and opioid overdoses within our communities.  While we were in Atlanta, we saw folks from our AD community who are working on opioid-specific academic detailing projects, including our colleagues at Alosa Health! If we didn’t catch you while we were there, please reach out to us at [email protected] and tell us about your experience in Atlanta! NaRCAD also had the opportunity to present with our colleagues from Comagine Health to share about our own collaborations and findings from a recent project, a 15-month clinic-based intervention called Improving Pain and Opioid Management in Primary Care (PINPOINT). The PINPOINT intervention was implemented in 36 clinics in Oregon and combined the Six Building Blocks, academic detailing, and practice facilitation approaches to improve pain management, opioid prescribing practices, and treatment of opioid use disorder in primary care settings.  A baseline survey of clinical staff and prescribers was conducted to assess knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding opioids. The survey results suggested differences between clinical staff and prescribers in behaviors and attitudes about opioid therapy for treatment of chronic pain, familiarity with opioid prescribing best practices, and opioid-related policies and procedures. The participants who attended the conference session were eager to learn about how they could implement academic detailing programs in their own communities. We’re excited to share about the importance of academic detailing at future conferences and continue to learn and grow alongside all of you. Interested in submitting a proposal with the NaRCAD team at a future conference? Email us at [email protected]! Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation! By Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD An interview with Lindsey C. Beardsley, Individual in Recovery. This month, we’re looking through the lens of the patient experience, something that all detailers and clinicians work so hard to improve. We’re pivoting to an interview with a person with use disorder, her experience with use and recovery, and the ways in which the patient experience can encourage detailers and clinicians to continue working together to improve outcomes for those who struggle with substance use. Tags: Harm Reduction, Opioid Safety  Anna: Hi, Lindsey! We’ve never featured a patient’s experience on our DETAILS blog - thank you for sharing space with me and telling a vulnerable story. Let’s dive right in. Can you tell me about your background? When were you first introduced to substances? Lindsey: I was brought up in Cape Cod, Massachusetts with two loving parents and a lot of friends. I had a typical childhood, but I always knew I was different. I was extremely impulsive. I loved food – that was my first addiction. Then it was dance, then soccer, then horses. I did everything to excess. I was first prescribed opioids after a knee surgery at 13 years old, and again after a second knee surgery at 14. Something clicked in my brain when I used those medications, and it opened a door that I couldn’t close. I was shut off to all emotion and it felt good to not feel anything. My use progressed from taking prescribed medications for pain to using heroin and becoming homeless, struggling to meet my most basic needs. Using drugs gave me a false sense of power that I wasn’t like any of my peers and that I could do what I wanted because I was different.  Anna: We hear many stories from patients about substance use starting after pain medications are prescribed during adolescence. Despite the power that you felt when you used, were you ever worried about the health effects of your drug use? Lindsey: I dated someone in my teenage years, and we often used together. Cape Cod is a small community and within a few weeks of dating him, my mom heard that he had Hepatitis C. My entire family was devastated, but I didn’t care at all – I couldn’t see how it would affect me. I think back to all the times I shared needles and drug supplies. Even if I tried to use new needles, everything looked the same and would get mixed up in the rush of using with other people. I would always have a little fear inside of me that I would overdose on my first time using again after being in treatment, but that fear never stopped me.  Anna: We know that substance use disorder is a medical condition and patients need professional support. When you felt ready to address that fear and seek treatment, were there healthcare resources or community supports that helped guide you towards recovery? Lindsey: I’m lucky to be in a state like Massachusetts where we have a lot of resources that the rest of the country doesn’t have. I was a frequent flyer at our detox facilities. When I was admitted, I was always paired with a peer that was in recovery. I often knew the peer; it gave me hope to hear the stories of recovery from people I knew and previously used drugs with. I was assigned a counselor, and we would discuss my treatment goals and next steps. The counselor would walk through every community resource within several miles of me, like partial hospitalization programs, sober homes, Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings, 12-step programs, and syringe exchange programs. We also have a mobile harm reduction center in my community. Before it existed, a woman in recovery started a needle exchange program out of her home. She sparked a need and desire for our community to learn more about harm reduction.  Anna: Many people don’t have access to substance use resources in their community, especially harm reduction services. Here at NaRCAD, we’re trying to encourage primary care clinicians to be able to provide those linkages to care and harm reduction services. What does harm reduction mean to you? Lindsey: I was against harm reduction for a long time because I was very involved in a 12-step fellowship where the primary purpose was complete abstinence from drugs. Harm reduction was a shift in mindset for me, but it’s pretty cut and dried. We’re reducing harm, saving lives, and preserving a sense of family and community. When we reduce harm, we allow a mom to be a part of her family again, we allow her to get a job, we allow her to get off the street and out of harm’s way. Harm reduction can allow people to return home. Anna: It’s valuable to know that a 12-step program and harm reduction can co-exist. What message about harm reduction would you want to share with members of your community? Lindsey: Harm reduction doesn’t enable drug use – use is going to continue until the person is ready to seek treatment. A simple approach to harm reduction, like syringe exchange, prevents the spread of infectious diseases and reduces needles in public and community spaces. It prevents someone from contracting Hepatitis C when they use drugs. Anna: We know that harm reduction plays a huge role in preventing drug-related deaths and offering access to services. There are many approaches to harm reduction and even using just one approach reduces so much harm. Let’s transition to talking about patient care. How would you want your care to look, or not look, when seeking help for substance use from a clinician?  Lindsey: I’d want to seek care in a safe space where I could share what drugs I use and how I use them without being punished, judged, or arrested. I would also want a space to discuss what’s going on in my life with someone who is educated enough to help me. I honestly wouldn’t want to listen to a clinician tell me about treatment options while I can sense that they’re judging me. A lot of clinicians have been through at least one training on substance use, but those trainings don’t change core beliefs and morals. Those trainings don’t change the way a clinician looks at you when you tell them you use substances. Anna: That’s true – having a trusting relationship with a clinician where you can share openly and not be judged is critical to effective care. How could clinicians have meaningful conversations with patients about substance use, especially if they have preconceived notions? Lindsey: Clinicians need to learn to have open, non-judgmental, inclusive discussions. That starts with asking all patients about their mental health and substance use history. Educators can provide clinicians with scripting tools if they feel uncomfortable having these conversations. Also, including peer support in the plan of care can help take some of the stress off of the clinician. This can include reviewing community resources and continuing the conversation with patients, while also educating the clinician on substance use through sharing personal experiences. We need to support patients, peers, and clinicians in doing this work and doing it as a team. Anna: I’m hearing you talk about so many elements that clinicians can use to improve patient care, like scripting tools and peer support. We’re continuing to work on ways to support educators and clinicians – your ideas will certainly help guide us. Thank you again for sharing your insights and being open to this conversation. We look forward to connecting with you again in the future! Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Lindsey C. Beardsley, an individual in long-term recovery, was born and raised in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. She was involved in many different sports growing up – gymnastics, soccer, and dance – but riding and working with horses quickly won over her time and heart from a young age. After many years of struggling with addiction, Lindsey walked into a treatment facility in August of 2018 and made the decision to stop using drugs one day at a time. Lindsey has been in recovery since September 21, 2018. By Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD An interview with Meghan Breckling, PharmD, BCACP, Ambulatory Care Pharmacist and Academic Detailer, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and Arkansas Department of Health. Tags: Detailing Visits, Opioid Safety, Harm Reduction, Evidence-Based Medicine  Overdose Deaths Rates per 100,000 people per County, Arkansas 2020 Overdose Deaths Rates per 100,000 people per County, Arkansas 2020 Anna: Hi, Meghan. Thanks for joining me on DETAILS today! Your team has done extensive work on pain management detailing, and you recently completed a pilot project on harm reduction in collaboration with the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO). Can you tell me a little more about this project? Meghan: Thanks for having me! We decided to target rural counties in Arkansas that have both high drug overdose deaths and naloxone administration rates. We previously created broad pain management materials for our other opioid safety detailing projects; this project took those materials to the next level. We looked at how we could better support clinicians in caring for their patients with substance use disorder (SUD) through a harm reduction lens. We provided clinicians with screening tools to help identify patients with mental health conditions and SUD to determine who could benefit from additional services. We even created a local resource guide for clinicians to easily connect patients to community services. The clinicians found that these accessible tools helped them have open conversations with patients.  Anna: I can imagine having something tangible to give to patients makes clinicians feel more equipped to have these conversations. What other resources were you able to share with clinicians? Meghan: We encouraged clinicians to utilize a new, free mental health resource called AR ConnectNow. This program provides immediate virtual care to all Arkansans dealing with mental health and substance use disorders. Clinicians were grateful for AR ConnectNow because mental health services are scarce in rural Arkansas; they’ve been sharing it with their patients frequently. Anna: You must have been proud to be part of a project that had such an impact on both patients and clinicians. How did the harm reduction lens inform your detailing visits for this project compared to your prior pain management-focused visits? Meghan: Many visits centered on communication with patients. Communication and empathy are two huge pieces to consider with this topic. We spent a lot of time asking clinicians about the conversations they have with patients and the types of questions they ask about substance use. We really wanted to understand what was going well and where there were gaps that we could help fill with resources and support. We also focused on naloxone prescribing and administration. We gave out free naloxone kits to all clinicians that they could either keep in the clinic or give to a patient who was having trouble accessing it. Clinicians were open to the idea of prescribing naloxone to patients who were at risk of overdose and open to keeping kits in their clinic in the event of an overdose. Our team had a lot of clinicians say during follow up visits that they felt more comfortable prescribing naloxone and were prescribing it more to patients and family members.  Anna: It’s impressive how you were able to clearly shift your focus from opioid prescribing to harm reduction and prioritize the relationship between the clinician and patient. Did you receive any pushback from clinicians on harm reduction? Meghan: Clinicians understood the need for harm reduction services but were more inclined to refer patients out rather than providing services within their clinics. For example, we found that a lot of clinicians were resistant to prescribing Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD), either because they were uncomfortable with the steps to do so, or they were told by leadership that they should not prescribe MOUD at their practice. It can sometimes take an hour or more for patients in rural areas to access specialty services that offer MOUD. We’re looking at future projects where we can utilize pharmacists to increase MOUD prescribing in partnership with primary care providers. For instance, a primary care clinician could diagnose SUD and prescribe MOUD, while a pharmacist could monitor the patient throughout treatment. It would take a lot of burden off the clinicians and could possibly make them less resistant to prescribing it.  Anna: Using pharmacists as an integral part of the care team is an excellent idea – you’ll have to let us know if you receive additional funding for this work! Let’s wrap up with a final question. If another program decided to do a detailing project on harm reduction, what advice would you give them before they went out into the field? Meghan: You need to take a step back and remember that there isn’t going to be instant behavior change among clinicians. For a topic this complex, it’s critical to have follow-up visits and continue to be a resource and support for clinicians. Also, be understanding of clinicians and their experiences. They’re dealing with a lot and it’s not easy to change things all at once. Building a relationship and getting a clinician to commit to just one key message is a huge win. Want to learn more? Read about the harm reduction key messages used for this project and the development of those messages on our previous blog post. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Dr. Meghan Breckling is an Ambulatory Care Pharmacy Specialist at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) and is a trained Academic Detailer through the National Resource Center for Academic Detailing (NARCAD) within the Center for Health Services Research (CHSR) at UAMS’ Psychiatric Research Institute (PRI). She previously completed a PGY1 Pharmacy Residency and PGY2 Ambulatory Care Residency at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS). Currently, she is a part of a multidisciplinary academic detailing team comprised of a pharmacist, physician and physical therapist that provide evidence-based solutions, tools and support for chronic pain management to primary care providers across the state of Arkansas. By Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD An interview with Shuchin Shukla, MD, MPH, Faculty Physician, Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC), NaRCAD Training Facilitator Tags: Harm Reduction, Detailing Visits, Evidence-Based Medicine, Opioid Safety  Anna: Welcome to the DETAILS blog, Shuchin! You wear many hats - you’re an addiction medicine physician, an academic detailer, and an academic detailing trainer. Tell us how you got started with academic detailing. Shuchin: I had an interest in marginalized populations and did my residency in the Bronx in New York City. I was a clinician in HIV care for several years before moving with my family to Western North Carolina. Soon after we moved, I began working at our Area Health Education Center (AHEC) and it was evident that addiction was the primary public health and clinical issue that was causing the most harm in my community. Fast forward a few years and one of my colleagues received a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grant and asked if I could attend a NaRCAD training to learn more about AD. The medical board and one of our pharmacists at the Department of Public Health were very interested in using AD for overdose prevention. We started with a pilot where we detailed 10 clinicians and slowly built our program. We now have multiple AD grants we’re working on, including one on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and one on harm reduction.  Anna: We often tell programs to start with a small pilot before growing their programs so that they can identify what went well and where there are opportunities for improvement, especially on new detailing topics like ACEs (e.g., key message adoption, clinician response, etc.). You do a lot of education around substance use disorder and mentioned that your team received a harm reduction grant for AD – what does harm reduction mean to you? Shuchin: The goal is, simply enough, to reduce the level of harm that a person may be facing. Harm reduction means having no expectation of a person's behavior and accepting the reality of what people live and do without judgement. It’s about being open with patients so that they’re more likely to come back for a visit where you can continue to have a conversation with them about getting a little bit healthier. There’s evidence to support harm reduction. The research shows that providing harm reduction services, whether it's naloxone or syringe exchange, reduces harm, but also decreases substance use and helps people engage in substance use care and treatment. Anna: Do you see harm reduction being used with other topics beyond substance use disorder?  Shuchin: There are tons of examples of harm reduction that are built into everything we do. Seatbelts, masks, fire escapes, smoke detectors, vaccines, and the FDA regulatory agency are all forms of harm reduction. As a society, we’ve never looked at substance use through this lens because using drugs is so stigmatized. Anna: I imagine it’s difficult to have detailing visits with clinicians because of the type of stigma associated with it, such as thinking that it’s some sort of moral failing. How have clinicians responded to detailing visits on harm reduction? Shuchin: Most of the teaching about harm reduction is unlearning all the inaccurate information we've been taught. We're taught if you use drugs, you're a bad person and you should be penalized. I remember watching the show Cops growing up and there was always a person of color laid out on a car resisting arrest. Law enforcement would pull out a bag of cocaine from the car and say they’ve saved the community. None of this is right, but I saw that on TV as a middle school kid. It’s easy to generate a lot of negative energy about substance use disorder and substances in general from these shows, and clinicians are part of that thinking too. Asking clinicians to talk to their patients about harm reduction is a lot different than asking them to check their Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) to ensure that patients aren’t receiving multiple prescriptions for controlled substances. Having a conversation with a patient takes empathy and thoughtfulness, whereas checking a PDMP does not. We’ve found that clinicians who have been the most resistant to harm reduction are those who have family members with substance use disorders. They are often angry, and rightfully so.  Anna: It’s imperative to be empathetic during detailing visits, especially on a topic that affects so many people. Let’s explore harm reduction from a different angle. How do your patients respond when you bring up harm reduction during your clinic visits? Shuchin: These are certainly challenging conversations to have, so you need to start off by letting patients know that they aren’t going to get in trouble for sharing this information and you need to acknowledge the trauma and stigma that surrounds substance use. Patients seem grateful that I approach conversations in a straightforward way that doesn’t stigmatize their use of drugs. I’ve never had a patient be offended or confused about why I was talking to them about harm reduction. Their eyes usually widen when I ask them things like how they use their drugs, how they cook their drugs, or where they get their drugs from. They often say, “I’ve never had a doctor like you.” Anna: You must spend a lot of time building trusting relationships with patients so that you can have these conversations. Shuchin: I do. It also helps that the organization I work for, our county commissioners, and our sheriff are all on board with harm reduction. There’s a lot of focus on Naloxone distribution among members of our community, such as law enforcement, first responders, and other clinicians. Our clinic prescribes a lot of medications for opioid use disorder, specifically buprenorphine, which is also a form of harm reduction. We have peer support specialists who meet patients where they’re at and start the conversation about harm reduction with them before they even have their first visit with me.  Anna: It’s definitely critical to have a community that supports the way you practice, as well your program’s AD messaging. Can you share a final tip for other detailers who are working on harm reduction? Shuchin: Harm reduction is an emotional topic for a lot of people, especially folks who are in frequent contact with people who use drugs, like emergency room clinicians or people with lived experience in their families. With this topic, paying attention to the emotions of the clinician you're detailing and acknowledging those emotions before jumping into your key messages is much more important than any other topic I’ve worked on. Be patient and empathetic – every visit counts toward making a change. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Shuchin Shukla, MD, MPH, was born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana. He completed medical school and public health school at Tulane University and completed a residency in family medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, New York. He worked in the South Bronx for 5 years following residency, providing primary care for adults and children, as well as for adults living with HIV. He also served as medical director for Montefiore Project INSPIRE, a primary care-based Hepatitis C treatment program. He then moved with his family to Asheville, North Carolina, where he currently serves at Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC) as faculty physician and Clinical Director of Health Integration. He is an associate clinical professor of medicine in the Department of Family Medicine at the School of Medicine, University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, and is a Diplomate of the American Board of Preventive Medicine, Board-Certified in Addiction Medicine. Additionally, he is a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar. He leads on various initiatives and projects around addiction, HIV, Hepatitis C, homelessness, and the criminal justice system. His main experience as a detailer has been focused on improving evidence-based provider interventions related to opioids, pain, and addiction. Honest Conversations: Supporting Clinicians in Linking Patients to Harm Reduction Services11/14/2022

By Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD Tags: Primary Care, Opioid Safety, Evidence Based Medicine, Harm Reduction  Our team at NaRCAD has been working on an exciting new project developing harm reduction key messages for primary care clinicians in collaboration with the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and consultants from Boston Medical Center. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines harm reduction as an approach that aims to prevent overdose and infectious disease transmission, improve physical and mental health, and offer options for accessing treatment and other health care services for people who use drugs. Various harm reduction approaches have been proven to prevent overdose and death, injury, infectious disease transmission, and substance misuse. For instance, there is nearly 30 years of research that has shown that syringe services programs decrease transmission of viral hepatitis, HIV, and other infections. There are several other harm reduction approaches beyond syringe service programs, including:

It’s critical that academic detailers continue to encourage primary care clinicians to discuss harm reduction with their patients and link them to services within their community. Academic detailers have the ability to empower clinicians to have difficult conversations with patients to reduce infections, overdose, and death. Our team developed the following key messages to support primary care clinicians in caring for patients who would benefit from harm reduction. These key messages are currently being piloted across the United States in a project funded by NACCHO.  Harm Reduction: Key Messages to Improve Outcomes for People Who Use Drugs 1. Assess factors that may contribute to risk of Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) for patients who use opioids. 2. Identify opportunities to reduce risk of harm using a patient-centered approach. 3. Offer Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) to patients identified as having OUD. 4. Connect patients with community harm reduction services and other services that meet identified needs. These evidence-based key messages can help clinicians provide support to their patients and build strong and trusting relationships with those who need it most. Building trust between clinicians and patients allows patients to feel heard and be open to seeking additional treatment, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes. Our team is looking forward to continuing to explore harm reduction and updating our key messages based on the results of the pilot through NACCHO. If your program is interested in collaborating with our team on future harm reduction work, or any other clinical topic, please reach out to us at [email protected]. Want to learn more? Stay tuned to learn about the results of the pilot and how clinicians responded to these key messages in the field. You can also join our discussion forum to interact with peers who are working on harm reduction! By Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD An interview with José Peña Bravo, PhD, Health Educator, Florida Department of Health in Duval County. Tags: Detailing Visits, Evidence-Based Medicine, Opioid Safety, Data  Anna: Hi, José! Thanks for joining us on our DETAILS blog today. Your journey that led you to the academic detailing community is unique – can you share that journey with us? José: Yes! My background is not originally in public health. I’m a biomedical researcher by training, specifically preclinical research using animal models. My dissertation work was on understanding the neurophysiological changes and different brain regions involved in behaviors related to substance use. My intention was to stay in academia and start my own lab, but my plans changed during COVID-19 and the opportunity to work with the public health department in Duval County presented itself. It’s been a learning curve for me to switch my perspective from preclinical research to public health—it’s been an enjoyable journey so far! Anna: I’m sure your biomedical research skills have a positive impact with clinicians during your detailing visits too, especially when clinicians want to discuss the neurobiology of substance use disorder. Speaking of visits, your detailing work is funded through CDC’s Overdose Data to Action (OD2A) grant, which seeks to prevent overdoses. Can you tell us about what the work for this grant looks like in Florida?  José: The OD2A project is a team effort across three CDC-funded jurisdictions in Florida. The health departments share that funding with various community organizations, and we all work toward linking patients with substance use disorder to treatment, mental health care, and care coordination services. Our detailing team is closely connected to organizations and resources within our community, and we share these resources with clinicians during our detailing visits. We also have access to aggregate prescription data from our jurisdiction and are continuing to find ways to present and incorporate this data at our visits with clinicians. We share this data and other resources across our three jurisdictions. Anna: We’ve found that many AD programs have been successful when they are closely connected to community resources. NaRCAD recently hosted a detailing training for OD2A recipients that you attended. What was it like to train with other jurisdictions working on the same project? José: It was helpful to hear from other jurisdictions because they’ve all approached their AD work differently based on the gaps in care in their own communities. I was able to hear from AD programs in rural areas and the specific challenges that their patients face with lack of access to care (long travel times, stigma, etc.). I also enjoyed practicing my detailing skills in a space where I felt comfortable making mistakes. It’s valuable to try things out and see how they’ll go before going out in the field. I learned a lot at the training and am excited to try out some of my new skills at my next visit.  Anna: Hearing from other detailers who are doing this important work with you is so helpful as you continue to think about and grow your own program. What advice would you tell other detailers working on the OD2A project? José: If you’re just starting out, reach out to community partners and get a sense of what patients with substance use disorder are experiencing and the challenges they’re facing before you start detailing clinicians. You’ll better be able to represent what is happening in the community and the resources that exist when you’ve done your research first! Anna: That’s terrific advice – a key piece of being an effective detailer is understanding the patient experience for the clinical topic you’re detailing on. So, what’s next for your work and Duval County? José: We’re currently working with our epidemiology team to collect population-level data and present it concisely. We want to be able to efficiently share this data with clinicians in a way that gets their attention and has them compare it to what they’re experiencing in their clinics to ensure an interactive dialogue during detailing visits. Anna: Using data to tell a story helps clinicians see the impact that they have in preventing overdoses and starts a conversation about organizations and resources that exist within communities for patients with substance use disorder. Thanks for sharing your OD2A work with us, José. We look forward to connecting with you and the other OD2A recipients at our conference in November! Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. José’s background is in Neuroscience preclinical research with over 10 years of experience in the field. His graduate work focused on the study of rodent models of substance abuse and the neurophysiological changes associated with controlled-substance experience. He has additional experience as an undergraduate and graduate level lecturer in different biomedical research topics. José recently transitioned to a position as health educator as part of the Overdose Data to Action (OD2A) program at the Florida Department of Health in Duval County. His role involves the implementation of the academic detailing program including outreach to clinics, integrating novel data and information to education materials, and keeping track of different metrics associated with outreach and AD sessions. An interview with Nicole Green, BSP, RPh, ACPR, DPLA, Director of the Ambulatory Pharmacy Services Program at ThedaCare, a healthcare organization based in northeastern and central Wisconsin serving both rural and urban areas. By: Aanchal Gupta, Program Coordinator, NaRCAD Tags: Program Management, Detailing Visits, Opioid Safety  Aanchal: Hi Nicole, thank you so much for talking about your program with us today! You’re a pharmacy director at ThedaCare—tell us more about the academic detailing component of your programming. Nicole: During the past four years working at ThedaCare, I’ve been studying ways in which pharmacists could serve as academic detailers to support opioid stewardship initiatives in order to positively influence prescribing. I was able to collaborate with other physician leaders as well as executive leadership who supported the program, gather data on opioid prescribing, and work on a proposal for academic detailing. We created our first formalized detailing project, called the Ambulatory Pharmacy Services Program, in January 2021. We had four detailers kick off our program and we’ve now doubled our team with a total of eight detailers that have all been trained by NaRCAD. Our detailers are ambulatory pharmacists who are embedded in ThedaCare’s family medicine and internal medicine clinics, serving as both medication experts and pharmacy consultants for patients and providers.  Aanchal: It’s incredible how quickly your program grew! Can you tell us more about the areas you’ve been focusing on for academic detailing? Nicole: Opioid stewardship is our main focus area for our detailing initiative. Our detailers identify patients who are candidates for Naloxone and work with clinicians to provide education to patients and their family members. The detailers also assess patients who have been on opioids for a long time and determine if they still need to be on them or if tapering should be considered. The second focus area is comprehensive medication management services for our self-insured population. This includes having our detailers identify chronic disease management gaps and partner with our state employees to optimize care for patients to reduce cost and readmissions. Our last focus area is to support our new heart failure clinic. Patients are referred to this clinic if they’ve been discharged from the hospital with heart failure or if they’ve been referred by a cardiologist. On initial visits, patients see a cardiology provider followed by an ambulatory pharmacist. Our role is to review the patient’s chart and provide recommendations to the team, as well as education to the patients. Our goals are to decrease readmissions and improve guideline-directed medical therapy.  Aanchal: Wow - your team’s impact is tremendous. You previously mentioned that you were able to double your detailing team in less than a year. What characteristics do you believe are needed to have a strong detailing team? Nicole: Having in-depth knowledge about the clinical topic is extremely important. Detailing is also about building trust and strengthening the relationship with confidence. Detailers need to be confident, especially when they’re first starting out and are meeting with providers that they have yet to build a relationship with. Detailers also need to be prepared to respond confidently and in a way that will still engage the providers in an open conversation. Providers typically don't understand that ambulatory pharmacists’ jobs are to assist patients to meet medication-related goals. There have been assumptions about why we’re delivering this service or why we’re meeting with clinicians. Clinicians ask questions such as, “Is it because I’m being targeted?” or “Is it because of my prescribing practices?”  Aanchal: Agreed; at NaRCAD, we know that having both clinical expertise and confidence communicating is essential to detail successfully. We know what makes a successful detailer – now let’s talk about what qualities you believe make you successful as a leader. Nicole: The first quality that comes to mind is passion. I lead with energy and show my team how exciting this work can be. I think that's important because previously we didn’t have pharmacists embedded in primary care and patients didn’t have an option to book an appointment with a pharmacist for consultation. Our pharmacists are delivering a service that was not there before. They need to promote themselves and make others aware of how they can help. Also, I like to be a strong advocate for my team. I constantly raise my hand saying that we can help with different initiatives or that certain projects are right up our alley.

Finally, I encourage my team to be persistent. We can't take the first “no” from a clinician as rejection. It might mean, “not now,” “I don't understand,” or “I haven't been exposed to this.” It doesn’t mean that they never want to have a visit with an academic detailer or will never change their prescribing behavior. Aanchal: These are all core elements in building a strong team. Some situations can feel defeating and having a strong leader that has your back is so important. Lastly, what advice do you have for someone who is new to managing a team of detailers? Nicole: Prepare your detailers for the field with the most up-to-date clinical content so that they can interact with clinicians confidently. Also, provide your detailers with training opportunities and use resources like NaRCAD. If you have the capacity, take it one step further by adding practice role play sessions among peers and allow new detailers to observe other detailers in the field. When training, help the detailers step out of their comfort zone within a group of people that they know before they step out of their comfort zone with a stranger. Aanchal: Yes, having support and receiving feedback from peers is an important element of building a strong team. Thank you so much for sharing your perspectives with us, Nicole! We look forward to continuing to see your team grow and feature your work at our upcoming conference! Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  BIOGRAPHY: Nicole Green completed her pharmacy education at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada followed by a hospital residency. She practiced for over a decade as a Clinical Coordinator primarily in the area of cardiology. She has completed year-long learnings through the AIMM (Alliance for Integrate Medication Management) collaborative as well as the ASHP PLA (Pharmacy Leadership Academy). She is the Director of Ambulatory Pharmacy with ThedaCare. She leads the comprehensive strategic plan to embed pharmacists within family and internal medicine clinics as providers and vital members of the primary care clinical team. She has served as an Executive panelist with GTMRx (Get the Medications Right) and the Institute for Advancing Health Value. Her program utilizes Academic Detailing as a means of building professional relationships, establishing credibility and influencing prescribing improvements. Much of her team’s work is related to Quality improvement initiatives in medication stewardship and safety as well as maximal performance in Pharmacy related ACO measures. Nicole has worked with the ThedaCare cardiology team to build a collaborative Heart Failure Clinic where patients see both a cardiology provider and am ambulatory pharmacist. By Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD An interview with Adrienne Butterwick, MPH, CHES, Senior Improvement Advisor and Academic Detailing Project Manager, Comagine Health. Comagine Health is a national, nonprofit, health care consulting firm that works collaboratively with patients, providers, payers and other stakeholders to reimagine, redesign and implement sustainable improvements in the health care system. Tags: Detailing Visits, Evidence Based, Substance Use, Opioid Safety  Anna: Hi Adrienne! We recently saw you present on a panel where you spoke about your academic detailing project with dentists on opioid safety. Can you tell us a little more about how your team got started with this work? Adrienne: In 2018, the CDC released funds to states through the Overdose Data to Action (OD2A) grant and the state of Utah selected academic detailing as one of the interventions they wanted to use. AD is one of the many different modalities that we use within my organization to reach clinicians to educate them and have an impact on the kind of care they provide. The state began looking at specific regions and populations to target after we received the funding. Utah is unique in that it has a high number of adolescents undergoing surgery for wisdom teeth removal, which is one of the most common instances where controlled substances are prescribed. A first prescription can be a huge turning point to potentially becoming addicted to a substance, especially at a young age. That’s when we decided to put together a team of two detailers to detail dentists. I was lucky enough to attend each detailing visit and collect data through pre- and post-surveys and answer any administrative questions that came up.  Anna: It’s impressive that your organization was able to look at the data in your state and build a program to fill a specific care need. What makes dentists and their environments unique when it comes to detailing? Adrienne: There’s a theory that providers who are prescribing controlled substances are working within systems and teams that are well-poised to understand the challenges of opioid prescribing. Dentists fall into a different healthcare model that’s often siloed; they aren’t usually affiliated with an overarching health system or university like many primary care providers are. This results in isolation, making the interactive, 1:1 outreach model of detailing even more important – we knew we needed to bring the information and support directly to them in their dental offices. Anna: Detailing seems like a critical need for isolated dentists, both in providing them with customized education, but also in building connections. Were there any special considerations that your team took into account as you worked with the dentists? Adrienne: The language that’s used in the dental world is very different than language that’s used in primary care. We were fortunate enough to have a dental provider, who’s a champion of AD, work with us as a detailer on our project. He knew the language, understood the workflow, and could speak to the need for safe opioid prescribing. He always started his detailing sessions with a personal story like, “When I took wisdom teeth out, I would always prescribe 40 Percocet pills. All I can think of today is, ‘what have I done?’” You could see the mood shift the moment he started talking about his personal experiences, allowing for a connection between himself and the dentists he met. The success of this program wouldn’t have gone even half as far without his support.  Anna: A detailer who can build empathy with clinicians and who has personal experience with a challenging topic is an important asset to have in a detailing program. What obstacles did you face as your team implemented this project? Adrienne: Connecting with dental offices, in general, was tough. We first started by working with dental associations to get relationships in place. We submitted newsletter articles, attended meetings, presented at the regional conference, and sent our program’s information via their listservs. We also Googled practices and found ones that had more than one dentist working in the office at a time. We’d cold call those offices and say, “It looks like you have a big operation – is there a way we could bring training in for your team for continuing education credits?” Before leaving the visits, we’d ask the dentists for referrals to other clinicians and leave flyers behind. Relationships grew organically over time. Anna: It sounds like the project began to build on itself fairly quickly. Did your team experience any barriers from the dentists during the detailing visits? Adrienne: We had a lot of dentists who thought the opioid crisis wasn’t relevant to their practice and we knew that we had to find ways to tie it into their profession. Fortunately, dentists have historically been involved in public health movements because they hold a different type of relationship with patients that is closer than a typical relationship with a primary care provider. They see patients more frequently and can detect small changes in health quickly. The dental profession was incredibly important in the tobacco cessation movement in the 1990s. They were instrumental in getting individuals to reduce or completely stop using tobacco. Dentists are also starting to be trained in domestic violence and human trafficking. For the dentists who were hesitant about the relevance of our detailing visits, we would say, “You have this amazing relationship with patients that we don’t see in other parts of healthcare—here’s how you can make a huge difference!” or “I can understand how there would be a lot of fear to step out of your comfort zone; we have a lot of resources and materials to support you.”  Anna: Dentists truly have a unique relationship with patients that can be used to promote countless public health initiatives. Can you think of a time your team was able to empower a dentist to change behavior and encourage them to see their relevance in combatting the opioid crisis? Adrienne: There was a dental group in a rural part of the state that had one dentist and a big support staff. We came in for a detailing visit and had a conversation with the entire office. After the meeting, one of the dental assistants pulled me aside and told me that a patient who had recently completed substance use rehab had visited the office in need of a procedure that would warrant prescribing an opioid. No one in the office knew what to do for pain control and they were all unsure how to approach the patient given his history. She said that because we came, she felt like she now knew how to have a conversation with him about the procedure and his safer, alternative options for pain management. The dentist also shared that prior to our visit, he often didn’t know how to handle conversations about pain management and opioids and wasn’t sure if it was his job to do so. After our visit, he said he felt comfortable and confident doing this, and shared an anecdote of being able to create a safe space for an ongoing conversation with a recent patient. Anna: It seems like your team has had such an impact by using one of the core elements of detailing – building relationships through empathy, validation, and support. Can you share some encouragement for readers who are considering having these conversations with dentists? Adrienne: Be flexible and don’t come in with your own agenda – be sure to let the dentists drive the conversation and let them teach you along the way. It can be a rewarding yet challenging experience – don’t forget to celebrate the small wins on your journey! Anna: Thanks for sharing this innovative approach to detailing, Adrienne! We’re looking forward to hearing about your continued impact with the dental community and beyond. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Ms. Butterwick is a Senior Improvement Advisor at Comagine Health. She is currently working on quality improvement efforts directed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to improve quality of care for residents living in post-acute and long term care as well as assisted living and home health. She's also working on an initiative to increase advance care practices in those settings. In addition, through a subcontract with the Utah Department of Health, Ms. Butterwick currently provides educational support for opioid prescribing to family medicine and dental providers. Her work with this contract has earned national recognition and has been presented at the RX Drug and Heroin Abuse Summit in April 2020 and the American Public Health Association’s annual conference in October 2020. She is currently also collaborating with faculty from the University of Utah regarding telehealth and advance care planning initiatives through the Utah Geriatric Education Consortium and Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Programs. She completed her Bachelors of Science degree in Behavioral Science and Health at the University of Utah in 2007 and her Master's in Public Health at Westminster College in 2014. She has also earned recognition as a Certified Healthcare Education Specialist (CHES). In her 15 years of public health project management she has also worked in rural health research, provider education programs and care management. She has a strong passion for quality improvement and public health. Supporting Clinicians in Utah: Working Together to Utilize Safe Opioid Prescribing Guidelines3/25/2022

An interview with Parveen Ghani, MBBS, MPH, MS, Health Program Specialist III, Division of Professional Licensing, State of Utah. by Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD Tags: Opioid Safety, Evidence Based, Training  Anna: Hi Parveen! You’re one of our training alumni who’s built a strong program over the past few years. We’re thrilled to be able to catch up with you! Can you tell us about yourself? Parveen: I’m trained as a physician and have always wanted to work in public health. It was important to me to be able to make a difference in people’s lives. I currently work in the Division of Professional Licensing at the Department of Commerce in Utah. I've been working as an academic detailer since my NaRCAD training a few years ago. Anna: It sounds like the rest is history! Are there other detailers on your team who are helping you meet your program goals? Parveen: I’m a full-time detailer for our AD program along with my colleague, Marie Frankos. We work with many of the same prescribers over multiple detailing visits and build strong connections with them.  Anna: Can you talk to us about your detailing work in overdose prevention? Parveen: Opioid overdose in the State of Utah is exceptionally high. We’re currently working with prescribers on the safe prescribing of opioids. Our state’s prescription drug monitoring program is called the Controlled Substance Database Program (CSD). The CSD includes both a Patient Dashboard and Prescriber Dashboard. The Patient Dashboard is an electronic clinical decision-making tool that grants prescribers access to information regarding controlled substance prescriptions for individual patients. It contains records of a patient’s poisoning or overdose and any violations associated with a controlled substance. The Prescriber Dashboard, on the other hand, tracks each clinician's prescribing patterns and CSD utilization behavior. Anna: We’ve seen a lot of success with detailing programs who work with clinicians to navigate their state’s prescription drug monitoring program, like your CSD. Does your state require prescribers to look at this database?  Parveen: Yes. According to the Utah Controlled Substances Act, (a) A prescriber shall check the database for information about a patient before the first time the prescriber gives a prescription to a patient for a Schedule II opioid or a Schedule III opioid. (b) If a prescriber is repeatedly prescribing a Schedule II opioid or Schedule III opioid to a patient, the prescriber shall periodically review information about the patient in: (i) the database; or (ii) other similar records of controlled substances the patient has filled. Anna: It’s so important to support prescribers in using a database like this, especially when there are mandates in place. What is the overall goal of your AD program? Parveen: The goal of our AD program is to provide recommendations to prescribers regarding best practices in the utilization of the CSD per the Controlled Substance Database Act. This includes identifying individual prescriber’s prescribing and dispensing patterns of controlled substances, identifying prescribers who are prescribing in an unprofessional or unlawful manner, and identifying polypharmacy, doctor shopping, poisoning, or overdoses. Anna: It sounds like your AD program is working hard to support clinicians in CSD utilization. What kind of resources have you developed for clinicians that work towards your program’s overall goal, and how do you make these materials accessible?  Parveen: We’ve created a toolkit that acts as a guide to help clinicians utilize the database and different resources within the community. During our in-person visits, we provide hard copies of materials that include screenshots of how to create a CSD account, reset CSD account passwords, and navigate the dashboards within the CSD. During our virtual AD sessions, we send these materials electronically. Additionally, we provide our contact information for further technical assistance, including our personal phone number, work phone number, and email address. We've made our toolkit available on our website along with prescriber FAQs. We’re continuing to update our website with helpful materials for clinicians. Anna: Making resources like this so accessible is key. Can you share some reflections on visits where you felt like you made a difference or were able to offer technical assistance? Parveen: I love helping prescribers, even if it is something as simple as walking them through the log-in process or resetting a password. I’ve had clinicians bring their entire medical team in for a detailing visit so that I can show everyone in the office how to use the database. One prescriber even told me after a visit that they would be sharing my name with a colleague and that I should expect a call to schedule a detailing visit. It’s lovely to get these types of referrals from the clinicians. Anna: Prescribers feeling thankful and impressed with your 1:1 support enough to refer you to their colleagues is a huge success! Let’s wrap up with one more question - what’s one tip you’d give to another academic detailer? Parveen: Find ways to collaborate. We can’t do it alone! Start working together with other programs and share information, especially community resources. We can really make a difference if we work together. Anna: I couldn’t agree more. Making community connections and sharing information allows for great success in accomplishing goals for both small and large initiatives. Our AD community will be able to glean a lot from your program’s successes, and we look forward to sharing more of your team’s expertise in the future. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Parveen Ghani has over eight years of work experience in public health. She obtained her Master in Public Health degree (MPH) from Walden University (Minneapolis, Minnesota). Following this, she worked for four years with the Office of Minority Health for the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Service. Parveen relocated to Idaho Falls in 2015 with her husband and began to pursue her career in bioinformatics. She obtained her master’s degree in Biomedical Informatics from the University of Utah in May 2018. Shortly after graduation, she started working as an Academic Detailing Specialist with the Division of Professional Licensing (DOPL), Salt Lake City, Utah. Before moving to the United States, Parveen earned her medical degree (MBBS) from Dhaka Medical College, Bangladesh. While not licensed in the United States, Parveen has worked as a physician in Bangladesh, Ireland, and Australia. Parveen enjoys working with the prescribers on the safe prescribing of opioids. Parveen loves to exercise, walk, read, play the piano, and play with her pet kitty in her leisure time. An interview with Carolyn Wilson, a Senior Health Program Coordinator at Ledge Light Health District. Ledge Light Health District is located in New London, Connecticut and is the regional health district serving the southern part of New London County. by Anna Morgan-Barsamian, MPH, RN, PMP, Senior Manager, Training & Education, NaRCAD Tags: Opioid Safety, Evidence Based Medicine, Substance Use  Ledge Light Healthwatch Ledge Light Healthwatch Anna: Carolyn, we’re thrilled to feature you on our DETAILS blog! I know you wear many hats – can you tell us about your current job role? Carolyn: I’m a health educator working within primary prevention, an academic detailer, and the host of our health district’s television program called Healthwatch. Healthwatch covers topics like mental health, physical health, disaster preparedness, general public health, COVID-19, environmental health, and disease prevention. I’ve been with Ledge Light Health District for 11 years. Anna: It seems like improving patient and community health outcomes is a common thread across all your roles. What primary prevention work or related projects complement your AD work? Carolyn: Depending on what topic I'm detailing on, I lean into my primary prevention work or the harm reduction work that my colleagues are working on. One of the larger initiatives I often share with clinicians during detailing visits is the Naloxone and Overdose Response App (NORA) project. The Department of Public Health developed a web-based application that can be downloaded directly to your phone. It has information about preventing, treating, and reporting opioid overdose. The app can be used by both folks in the community and clinicians. I also speak to clinicians about proper medication storage and disposal while promoting our “Take it To The Box” Initiative.  Anna: We love to see programs using AD to spread the word about broader, community-focused initiatives. Are there other ways that your opioid-related AD work overlaps with work being done within your department? Carolyn: Yes! I’m so lucky to be able to work in the office side-by-side a recovery navigator. She helps link folks in the community to addiction services. Every day we say things like, “hey, I overheard you talking to that pharmacist just now – do they know x clinician?” We often share resources and try to work together to ensure that community health goals are achieved, often by making sure that the work people are doing is connected rather than existing within silos. It all comes down to helping one another work towards a common goal. Anna: What better way to work towards a common goal than to share resources across colleagues and projects! Can you share a story from the field where there was an intersection among various projects?  Carolyn: I detail a lot of advanced practice nurses (APRNs) and also work with them on some of my primary prevention projects. The overlap in projects helps me build strong relationships with these clinicians. I sometimes work with school-based health centers as part of my prevention work, and these health centers are typically run by APRNs. These centers act as an access point to care for many students and families. It’s essentially a primary care clinic right in the school. The Child and Family Agency oversees the school-based health centers in southeastern Connecticut and reached out to me after a horrific event in a Connecticut middle school. A few months ago, a 12-year-old got access to fentanyl and brought it to school. He overdosed and passed away a few days later at the hospital. We haven’t seen many overdoses in schools, but after this happened, a lot of schools started looking at their policies and school-based health centers wanted to have naloxone on hand. The medical director of the Child and Family Agency advocated for a policy that required all school-based health centers to have naloxone and to be trained in administering it. Anna: What a devastating story. Have the school-based health centers been able to put these types of new policies into place? Carolyn: When one of the clinicians from the Child and Family Agency reached out to me, she said, “Carolyn, I know you do this kind of work. You trained me in naloxone not too long ago during an academic detailing visit. I’d like to have a naloxone training for my nurse practitioners in the school-based health centers. I want naloxone available in all of our clinics.” This type of request would typically be delegated to somebody else in our department, but because of the relationships I had built through academic detailing, I was asked to provide the training, and I did. As a result, the school-based health centers now all have access to naloxone and the clinicians know how to administer it.  Anna: It’s incredible that you’d built trusting relationships with clinicians enough to be asked to provide this training, contributing to changing a policy in a span of one or two months. Carolyn: It means a lot that they came to me because they trusted me and knew I could get it done for them. I truly don't think I would have been involved if it wasn’t for my academic detailing work. Anna: I agree. It’s been a pleasure learning about your work and your unique approach to academic detailing. We’re excited to follow along with you on your AD journey as you continue to promote health across your community. Have thoughts on our DETAILS Blog posts? You can head on over to our Discussion Forum to continue the conversation!  Biography. Carolyn Wilson is a health educator and prevention specialist serving as a program coordinator at Ledge Light Health District in New London CT for 11 years. Carolyn studied public health and health education at New York Medical College. Keenly interested in health promotion and behavioral science, Carolyn enjoys bringing her passions and talents to both primary prevention and academic detailing work. Carolyn has been serving as an academic detailer for over 2 years and enjoys speaking with clinicians about strategies to prevent opioid related deaths. Carolyn also manages the Groton Alliance for Substance abuse Prevention @Groton_Prevents. In her spare time, Carolyn enjoys serving on the Board of Directors for the CT Association of Prevention Professionals and Fiddleheads Food Cooperative. To connect with Carolyn, find her on LinkedIn. Aanchal Gupta, NaRCAD Program Coordinator Tags: Conference, Detailing Visits, Stigma, E Detailing, Opioid Safety Take a peek at the NaRCAD2021 conference materials on our Conference Hub.  Fresh from our move to Boston Medical Center, our team at NaRCAD hosted the 9th annual International Conference on Academic Detailing, a virtual event concentrating on “Cultivating Relationships for Community Resilience.” There were robust discussions on critical topics, useful tools shared, and connections built. With over 300 registrants from across the globe, the AD community continues to learn and grow thanks to your support and passion for this work. Check out some of the highlights from our 2021 conference below. Day 1 + 2 Welcome Addresses

Field Presentations

Breakout Sessions

Expert Panels

Special Presentation: “Detailer Training in Action: Ask the Experts”

Real-time Roundtable

Our team at NaRCAD is immensely grateful for your continued feedback and insights during our conference. This community has a wealth of knowledge to share, and as we approach 2022, we plan to continue to facilitate opportunities to connect you with others in the field, create a space to have conversations about stigma, and support your needs in the field. We look forward to seeing you in 2022. -The NaRCAD Team A special thank you to all of our NaRCAD2021 presenters! |

| Elisabeth Fowlie Mock, MD, MPH, FAAFP is a self-employed Family Physician consultant living in Holden, Maine. She attended Vanderbilt Medical School and obtained a Master’s in Public Health at UNC-Chapel Hill. She is a clinical educator for the Maine state Academic Detailing program (MICIS) and Alosa Health in Boston. She is Board Certified in both Family Medicine and Addiction Medicine. Her part-time clinical work includes evening shifts as a hospitalist and prescribing at a high-risk, low-barrier buprenorphine clinic. She is passionate about women’s and girls’ basketball, travel, learning chess and singing. |

Wearing Multiple Hats at Alosa Health: Detailing Clinicians, Managing Programs, and Training Staff

1/22/2020

by Anna Morgan, RN, BSN, MPH, NaRCAD Program Manager

Tags: Detailing Visits, Opioid Safety, Program Management, Training

Tony: Our partnership with Aetna, a managed health care company and health care insurer. We’ve been working with them to provide educational outreach to providers on chronic pain, acute pain, and opioid use disorder (OUD); supporting them in managing pain using non-opioid drug options; appropriately dosing opioids when they need to be used; tapering down patients who are on existing high doses of opioids; and helping to identify patients that may have opioid use disorder. We’re now working in Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, Ohio, Illinois and Maine.

Tony: When I’m training and managing detailers, I see myself more as a coach than a trainer. I’ve always liked educating and teaching—I enjoy helping others develop their skills and seeing them improve. Training folks and coaching them in the field is rewarding to me because I feel that I’m impacting what they’re doing in their own communities. It brings me happiness to see others succeed.

Tony: When I work with detailers in the field, I can see firsthand that they are able to be impactful with the providers because they are bringing about behavior change with their message delivery and confidence. We can also measure how impactful our work is by reviewing our Salesforce data. I can see from the detailer’s visit notes when providers have agreed to a behavior change, and this is a true measure of our work being impactful.

Tony: The major challenge is teaching detailers to have a conversation with clinicians rather than a lecture. Making the visit more conversational doesn’t often come as naturally as presenting the information in a lecture format, but the conversation must be about understanding where the provider is now, what their needs might be, and how to deliver content to make behavior change.

NaRCAD: With these challenges in mind, how do you instill confidence in academic detailers as a trainer and as a manager?

As a manager in the field, it’s quite similar. I usually sit down with each detailer after a visit and discuss what worked well and what they could do differently in their next visit, so that each visit becomes a learning opportunity. Providing feedback and being a mirror for the detailers helps them to build confidence and skills as time goes on. I also offer the detailers my perspective; having spent time doing this myself and observing others, I can share the tricks, skills, and wording I’ve heard throughout my time with the detailers.

Tony: Don’t be afraid to ask for a specific behavior change, and remember to follow up to make sure that the behavior change occurs. One thing that I find to be hard for academic detailers is the “ask”, where detailers are asking for commitment or behavior change from a provider at the end of the visit. I always tell detailers to frame it as, “based on what you’ve heard today, what is one thing you’d do differently?” Follow-up then ensures that providers are committed to change and holds them accountable for what they said they would do.

Tony: As a manager who’s coaching or guiding others, it’s important to build trust between yourself and the folks you’re coaching or managing. It can be lonely when you’re in the field detailing by yourself, so managers need to have touchpoints with their detailers. Building trust and having your detailers know you’re all working together helps them stay self-motivated; it makes them want to go out into the field and do a good job because they know someone is backing them up.

NaRCAD: Thank you for taking the time to chat with us today. We value your unique perspective on detailing, managing, and training!

Tony de Melo manages field staff and leads academic detailer trainings at Alosa Health. He attended Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences in Boston, where he received a BS in Pharmacy with a minor in Business Administration. This business interest led him to work for several pharmaceutical companies as a sales representative, account manager, training manager, district/regional manager, associate director of managed markets training, head of sales training, and development & marketing product manager. He has also worked for smaller businesses that were looking to grow their sales and marketing programs. Throughout his career, Tony has successfully sold, marketed, trained, led, designed, developed and executed solutions to meet business objectives.

Tags: Director's Letter, HIV/AIDS, Opioid Safety, Training

As NaRCAD enters its 10th year as the only national resource center dedicated to clinical outreach education, we’re ready to take our collaborations with you to the next level. The strength and sustainability of NaRCAD has grown from the hard work we’ve done together with you, our community members in the field.

We’re committed to continuing to provide the technical assistance you need to make your programs innovative, efficient, and successful. As we kick off 2020, our entire team at NaRCAD invites you to join us in leading our field forward through strategic partnerships, resource-sharing, and peer learning, all to implement important initiatives that will have a significant impact on clinicians and their patients.

The nature of our role as a resource center has continued to grow in parallel with increased recognition of the importance of academic detailing as a strategy to address multiple clinical challenges. We’ve been especially excited to see the effectiveness of AD enhanced when aligned with other initiatives to improve the quality of care.

Responding to this growing demand, we’ve dramatically expanded our reach, conducting 20 trainings in 15 different states across the US in the past two years alone, and 2020 looks to be no different. With the increased demand for AD technical assistance, we have a busy year ahead of us, from capturing your successes and sharing them via our DETAILS Blog to training your detailers to be ready for field work (and troubleshooting challenges along the way.)

We’re equally excited to have launched a new CDC research grant in collaboration with the Oregon Health Authority to rigorously evaluate the impact of their OD2A intervention and to develop a model for pragmatic assessment of similar efforts in other states. If you’re also interested in evaluating the impact of your AD program, reach out and let us know—we’re eager to hear from you.

Happy New Year!

-Mike

Michael Fischer, MD, MS, Director, NaRCAD

Dr. Fischer is a general internist, pharmacoepidemiologist, and health services researcher. He is an Associate Professor of Medicine at Harvard and a clinically active primary care physician and educator at Brigham & Women’s Hospital. With extensive experience in designing and evaluating interventions to improve medication use, he has published numerous studies demonstrating potential gains from improved prescribing. Read more.

Highlighting Best Practices

We highlight what's working in clinical education through interviews, features, event recaps, and guest blogs, offering clinical educators the chance to share successes and lessons learned from around the country & beyond.

Search Archives

by Topic:

All

ADvice

Autism

Cancer

Cardiovascular Health

Chronic Illness

CME

Conference

COVID 19

Data

Deprescribing

Detailing Visits

Diabetes

Director's Letter

E Detailing

Elderly Care

Evaluation

Evidence Based Medicine

Expert Trainer Insight Series

Harm Reduction

Health Disparities

Health Policy

Hepatitis C

HIV/AIDS

International

Jerry Avorn

LOOPR

Materials Development

Medications

Mental Health

Obesity

Opioid Safety

Pediatrics

Podcast Series

Practice Facilitation

PrEP

Primary Care

Program Management

Rural AD Programs

Sexual Health

Smoking Cessation

Stigma

Substance Use

Sustainability

Training

Vaccinations