|

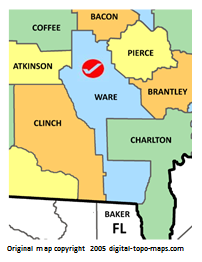

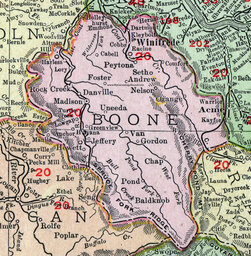

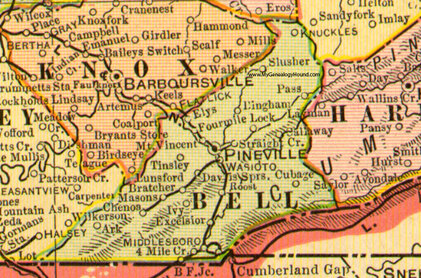

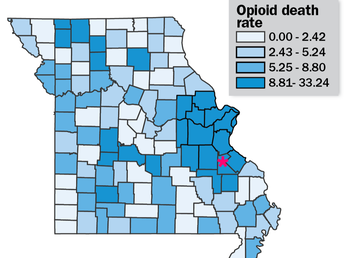

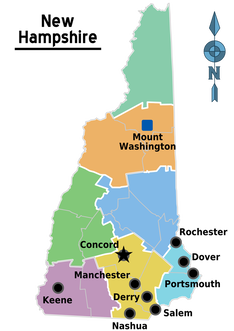

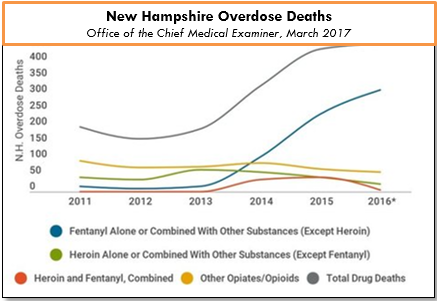

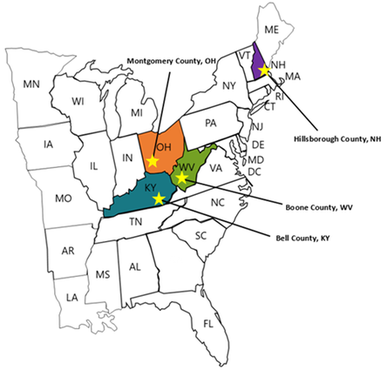

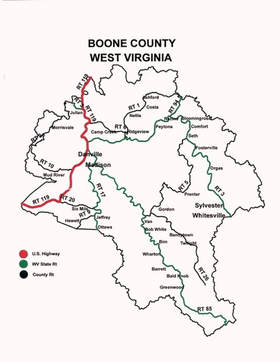

An interview with Dr. Rosemarie Parks, District Health Director, Ware County Public Health Department OVERVIEW: Ware County, Georgia, was one of 2 sites selected for year 2 of a pilot program of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), NACCHO (the National Association of County and City Health Officials), and our team at NaRCAD (The National Resource Center for Academic Detailing). This exciting pilot program focused on community-level work with local public health departments to develop customized interventions to reduce opioid overdose and death. Six sites experiencing significant public health problems related to opioids were selected over the two years to be trained in academic detailing; those trained health professionals then conducted 1:1 field visits with front line clinicians to impact behavior around prescribing, treatment referrals, and patient care, all within a rural area. As year 2 comes to a close, we’re showcasing stories from the field. Tags: LOOPR, Opioid Safety, Rural AD Programs, Substance Use  NaRCAD: Thanks so much for joining us to share how your detailing project has gone in Ware County, Georgia, Dr. Parks. Can you talk to us a bit about how the opioid crisis has presented itself in your community? Rosemarie: Our agency serves 16 counties in Southeast Georgia, and we have seen the same things across all of these counties. The opioid crisis affects the community across the board; in every sector. Law enforcement is seeking the effects of this crisis, so is healthcare, and people that work with children and families. They all acknowledge that they’re seeing it in their day-to-day work. So many public health topics only affect one sector, but this opioid crisis affects them all. NaRCAD: With it affecting so many, did you think the strategy of academic detailing would lend itself to improving patient health in response to the opioid crisis in Ware County? Rosemarie: Being a clinician myself, I did initially see how academic detailing would be a good public health intervention. I thought academic detailing would make the lives of providers better by providing them with evidence-based information and resources. As we discussed during the training with NaRCAD, there’s so much information out there, and it’s really difficult to sort through all of it.  In public health, we’re facilitators, data people, and information sharers. I really believed AD would work when I saw the statistics about Ware County during the 2-day training. Ware County is the highest prescribing county in the state, and the 12th highest prescribing county in the nation. Those statistics are eye-opening, and I believed that would make detailing successful in Ware County by raising awareness of how the opioid crisis is impacting our own community. NaRCAD: You mentioned being a clinician—you’re also the Public Health Director for your district. How does being both a clinician and the Public Health Director make it easier for you to be successful as a detailer? Rosemarie: My position allowed me to easily make appointments, and I did not have difficulties getting in the door, like so many other detailers do. I often had visits that were a lot longer than the usual 15 minutes, because clinicians would set aside more time to talk to me. My clinical experience as a primary care physician in private practice for many years made is so that I could relate to the clinicians, and allowed for more honest sharing. I would tell other doctors what worked and didn’t work for my practice, and that made them more comfortable opening up about their own experiences.  NaRCAD: That’s excellent—this is an example of how pre-existing relationships and a fusion of both experience in clinical care as well as public health can really merge to encourage change. What else was unique about your detailing experience? Rosemarie: Another thing that was unique in Ware County is we did both 1:1 visits, as the original model suggests, as well as group visits. There were many occasions upon which multiple providers and key leadership from a health system were all together in one room. This allowed providers to hear from other providers, and I saw that as a critical dynamic. The conversations continued well after those visits ended, and still continue to this day. It was also important that key leadership was present because they heard exactly how the issue is impacting clinicians and patients, and they have the power to make decisions affecting opioids in their health system. NaRCAD: It’s great to hear that a group education approach worked so well. What would you say has been the most impactful piece of this intervention? Rosemarie: I think academic detailing for the opioid crisis worked so well in Ware County because public health is seen as a neutral entity, and because of that, we were able to effectively facilitate these discussions. We do a lot of work in the healthcare community but it is rare that the public health department takes the time to visit an individual practice or provider. During my visits, I witnessed clinicians take in the data about how Ware is one of the highest prescribing counties in the nation, and saw how it immediately encouraged them to want to make a change.  After answering initial questions about where the data came from, clinicians were open to discussing things in more detail, and were consistent in enacting the CDC’s opioid stewardship recommendations, especially consistently using the PDMP. It also gave clinicians the opportunity to express concerns and challenges they face in their daily practices. NaRCAD: We’re so glad academic detailing has been impactful in your community. What has the greatest challenge been with implementing a successful academic detailing intervention to improve opioid safety in Ware County? Rosemarie: The overall experience has been fantastic. As we discussed, the providers were really open and honest. For me personally, as a detailer, it was difficult not to feel like I needed to be the one who had all the answers. I handled this by being a link to information, rather than having all of the information myself. For instance, when a clinician asked a question, or requested a resource I didn’t know about, I’d say something along the lines of, “Let me do some research about that, and when I come back I’ll be sure to have that information.” It helped when I was able to give the disclaimer that “I’m by no means the expert, but I’ve learned a tremendous amount about opioids and the crisis, and I’m here to share some of that information with you. And if I don’t know the answer to something, I can find someone who does.”  NaRCAD: That’s a great way to handle that kind of situation, and academic detailers are indeed the connector to resources, and certainly don’t need to know all of the answers. Well-handled! And speaking of not knowing all the answers, what is something you wish you knew prior to joining the LOOPR Academic Detailing project? Rosemarie: Personally, there were no big surprises. Everyone did a great job in explanting the process, executing the training, and providing resources. Like anything though, you don’t really get the hang of it until you get those first few visits under your belt and become more comfortable. Overall, this has been a great experience. It was so helpful having additional resources, learning from people that are highly knowledgeable and respected in this field, and being able to share experiences across all LOOPR sites with other detailers who are doing the same work.  Biography. Dr. Rosemarie D. Parks serves as the District Health Director for the Southeast Health District (District 9-2, Waycross, GA). She has overseen the 16 county health departments, 3 wellness clinics, and over 50 programs since moving to rural Georgia from Ohio in 2005. Dr. Parks holds a Master of Public Health degree from Youngstown State University, Ohio, and a Medical Doctorate from the Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine. She is board certified in internal medicine. She is also a member of the National Association of County and City Health Officials. As the District Health Director for the past 14 years, Dr. Parks has overseen telemedicine and teledentistry projects that have expanded new technology to meet the ever-growing needs of a rural population. She has also worked diligently with community partners in planning to combat the opioid epidemic and strategized for innovative solutions to meet the public health needs of the community. OVERVIEW: Boone County, West Virginia was one of 4 original site selected for years 1 + 2 of a pilot program of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), NACCHO (the National Association of County and City Health Officials), and our team at NaRCAD (The National Resource Center for Academic Detailing). This exciting pilot program focused on community-level work with local public health departments to develop customized interventions to reduce opioid overdose and death. Six sites experiencing significant public health problems related to opioids were selected over the two years to be trained in academic detailing; those trained health professionals then conducted 1:1 field visits with front line clinicians to impact behavior around prescribing, treatment referrals, and patient care, all within a rural area. As year 2 comes to a close, we’re showcasing stories from the field. Tags: Detailing Visits, LOOPR, Opioid Safety, Program Management, Rural AD Programs  Via NaRCAD, NACCHO, & the CDC’s pilot project, “LOOPR”, we were able to connect with high-burden counties across the U.S. whose rates of high prescribing and high fatal and non-fatal overdoses identified them as a county in need of support. NaRCAD worked on the implementation of an academic detailing initiative over the course of 2017-2019 with Boone County, located in rural West Virginia. Boone County ranks as the 22nd most vulnerable county across all counties in the United States, with the highest drug overdose mortality rate of all counties in West Virginia. Due to these and other data, Boone was identified as a key county in which to test the implementation of an academic detailing program, in which trained detailers would speak to clinicians and pharmacists about safer prescribing of opioids, checking the state’s prescription drug monitoring program to avoid dangerous co-prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines, and to try and provide treatment, non-opioid therapy, and resources to patients in need.  One of the most unique approaches across all 5 sites of the LOOPR Project was carried out in Boone, with the team of 5 detailers being hand-selected from the nearby University of Charleston West Virginia’s School of Pharmacy. Four of these five recruited detailers were students in training to become pharmacists; one detailer works at the university as a professor of pharmacy. Selecting pharmacy students and faculty allowed for many positive approaches to the project, as well as creating unforeseen challenges. Programs considering hiring student detailers can often rely on the flexibility of students’ schedules, as well as an enthusiasm and energy for learning that may exist in smaller quantities later in one’s career, when full-time roles in healthcare take priority. While many career-established clinicians may have little room in their schedules to squeeze in 1:1 sessions with fellow clinicians, students may have more of an ability to shift their schedules, especially if they are not yet carrying out residency.  a reflections from Boone County’s Detailing Team, it’s clear that best practices in detailing should also consider the vast amounts of new information that students are absorbing early in their learning careers, and that learning clinical content may take longer to grasp. In addition, the comfort level with new clinical information may lead to less confidence in discussing best practices, especially with clinicians whose careers are much more established. Finding the right balance of tenacity, communications savvy, more time to ramp up to comfort in delivering and leading 1:1 sessions, an additional amount of technical assistance provided at more frequent intervals, and additional practice time or shadowing time with a mentor, can all benefit student detailers who are training to join a clinical outreach education team in a high burden area. With these elements in place, a student detailer may be poised for success—however, other considerations include the fact that students may have new projects, graduation pending, or life events which may end up limiting their ability to dedicate consistent time to a project rolled out over many months.  Other reflections from the Boone County AD Team included looking carefully at the social climate in which AD interventions of this nature may be implemented. While no county is free of potential clinician-level or community-level stigma, particularly around issues such as opioid use disorder, Boone’s AD team shared a particularly challenging setting within which the local community was not as supportive of evidence-based harm reduction initiatives as would be beneficial. One detailer’s suggestion to raise the visibility of and advocacy for harm reduction included considering a public health campaign prior to a detailing campaign, to ensure that subsequent roll-out of detailing is more sustainable and met with an openness from clinicians to consider behavior change. NaRCAD’s work with the public health department in Boone County, in partnership with the students and faculty of University of Charleston, West Virginia, provided the kinds of insights critical to learning from a pilot project of this nature. As with many pilot studies, any information gathered can illustrate a clearer picture of the landscape within which public health initiatives can be implemented, so that future projects may have a greater impact. With many thanks to the student and faculty team of Boone County’s Academic Detailing Project team, we and our partners are grateful to have learned so much over the past two years. An Interview with Lutricia Woods, RN OVERVIEW: Bell County, Kentucky was one of 4 original sites selected for years 1 + 2 of a pilot program of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), NACCHO (the National Association of County and City Health Officials), and our team at NaRCAD (The National Resource Center for Academic Detailing). This exciting pilot program focused on community-level work with local public health departments to develop customized interventions to reduce opioid overdose and death. Six sites experiencing significant public health problems related to opioids were selected over the two years to be trained in academic detailing; those trained health professionals then conducted 1:1 field visits with front line clinicians to impact behavior around prescribing, treatment referrals, and patient care, all within a rural area. As year 2 comes to a close, we’re showcasing stories from the field. Tags: Detailing Visits, LOOPR, Opioid Safety, Rural AD Programs, Substance Use  NaRCAD: Hi Lutricia, thanks so much for taking the time to speak with us about your work as an academic detailer for the opioid crisis in your community. Can you talk to us about how the opioid crisis has presented itself in Bell County, Kentucky? Lutricia: There’s not a family in this community that hasn’t been touched by the opioid crisis in some way. Twenty years ago, I worked in hospitals as an RN discharging patients and providing them with their prescriptions as they prepared to go home. At the time, I was shocked at the rates of prescriptions of opioids with benzodiazepines, and patients thinking it was safe. From my perspective, in our community, the opioid crisis really began by doctors beginning to prescribe many opioids to their patients without education or an understanding of the dangers. Three years ago, I was working on a project at a middle school, and was surprised by the number of grandparents that were raising their grandchildren because their children were either in jail, or otherwise affected by opioid use disorder [OUD]. In Bell County, we also have so many people unable to find a job because they cannot pass a drug test, and once that happens, they return to use because of the stressors of not being able to find a job and pay their bills, and it becomes a challenging cycle to overcome.  NaRCAD: Thanks for sharing your perspective, Lutricia—it can be true that some clinicians don’t see the impact of their role in prescribing opioids, and many times may believe that people who develop an opioid use disorder do so because of a moral failing, rather than seeing it as a medical issue. Did you think 1:1 outreach, provided directly to prescribing clinicians, would lend itself to improving patient health in response to the opioid crisis in this community? Lutricia: I desperately hoped it would. The opioid crisis is very personal to me, as it is to many people in our community. Years ago, my mom had 2 surgeries within 6 months. She had complications from one of those surgeries, and as a result, she was in the hospital for 6 weeks, during which time her care providers did not wean her off of the opioids she took immediately after the surgery. She returned home with prescriptions for opioids at a high dosage, and she developed opioid use disorder. My mother’s doctor, with whom I worked, reached out to have a conversation with me. He told me that I had to be the one to intervene with my mother because she continued requesting more opioids. I conveyed that I wanted her to discontinue taking them, and that he needed to assist us in finding a way to do this, as I felt his prescribing without discussing safety caused the initial issue. His response was that he wanted to “keep her happy.” My mother struggled for the rest of her life; she was able to completely wean off and discontinue using them, but it required a lot of counseling. As a result of this experience, I became a drug education coordinator, as I really wanted to do my part to mend the opioid crisis by providing drug education for every student in the county. And then, of course, I became an academic detailer for this project over the course of the past 2 years, which involves clinician education about safety and risk of opioid prescribing.  NaRCAD: Thank you for sharing that Lutricia; the opioid crisis is personal to so many of us. What would you say has been the most impactful piece of this academic detailing intervention as you went into the field and spoke with clinicians? Lutricia: The most impactful piece has been the ways in which we’re trying to hold clinicians accountable for their roles in the crisis, as well as leveraging their ability to improve things based on their relationships with their patients. For many of the doctors and nurses I met with, our conversations and educational resources have made them more thoughtful and intentional about their role. They seem to realize more that they have the power to decrease the number of prescriptions they write, the length of time for which they write them, and talk more with their patients about safety. NaRCAD: That’s fantastic. What about the most challenging part of this project—what’s been hardest about meeting with clinicians to talk about the opioid crisis in Bell County? Lutricia: Getting an appointment to go in and meet with these clinicians has been so frustrating and challenging. I always say that the receptionists in doctors’ offices are the most powerful people in the world. If you can’t get through them, you’re not going to get what you need, and it is the same with the patients. I couldn’t even get in to see my husband’s doctor, who we’ve known since we were kids. My husband had an appointment, so I resorted to going with him, and did a detailing visit on the spot with his doctor. This same doctor ended up changing practices, and it’s been a lot easier to get into that practice—all because of the office manager. Those relationships are important.  NaRCAD: Getting in the door is definitely a consistent challenge across many programs. We’ve heard from other detailers that practice makes perfect, and sometimes it’s easier to gain access when you actually show up and request a meeting in person. What else did you learn after being in the field? Lutricia: When I was “volun-told” that I would be attending a training, and doing “academic detailing”, I didn’t truly understand what it was or what the impact would be. I’m a big picture person, and I couldn’t see the big picture at all; I went into that training not knowing what to expect. It wasn’t until I actually started making visits that I could start to see the seeds we were planting to begin to have an impact. Share your thoughts on this piece in the comments section below, or learn more about the LOOPR project and other opioid safety academic detailing initiatives here and on our Detailing Directory. Moving Beyond Skepticism: Partnerships to Improve Health Outcomes in St. Francois County, Missouri7/24/2019 An Interview with Amber Elliot, BSN, RN, Assistant Director, St. Francois County Health Center St. Francois County, Missouri was one of two sites selected for year 2 of a pilot program of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), NACCHO (the National Association of County and City Health Officials), and NaRCAD (The National Resource Center for Academic Detailing). This exciting pilot program focused on community-level work with local public health departments to develop customized interventions to reduce opioid overdose and death. Six sites experiencing significant public health problems related to opioids were selected over the two years to be trained in academic detailing; those trained health professionals then conducted 1:1 field visits with front line clinicians to impact behavior around prescribing, treatment referrals, and patient care, all within a rural area. As year 2 comes to a close, we’re showcasing stories from the field. Tags: LOOPR, Opioid Safety, Program Management, Rural AD Programs  Bureau of Vital Statistics, Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services Bureau of Vital Statistics, Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services NaRCAD: Thanks for joining us to talk about academic detailing in St. Francois, Amber. Let’s start the conversation with some background information about your county. How has the opioid crisis presented itself in your community? Amber: As with many other places, St. Francois County has certainly felt the impact from the opioid crisis. We have high rates of overdoses and over-prescribing. There have also been more children in foster homes because their parents have an opioid use disorder, as well as increasing drug arrest rates. Many aspects of our community have been affected in some way or another. I think this is the main reason why so many community agencies have come together to start working on this issue.  NaRCAD: Why did you think the strategy of academic detailing would lend itself to improving patient health in response to the opioid crisis in your community? Amber: Academic detailing is a great strategy to reach out directly to clinicians in their offices in order to provide resources and supportive education without punitive actions. We really weren’t sure what to expect with having two nurse practitioners, two registered nurses, and a pharmacist carrying out the 1:1 detailing visits. Health Center administration and detailers were skeptical of how physicians would react to other disciplines “telling them how to do their job”. However, academic detailing isn’t telling them what to do, it’s talking with them about what they can do to keep their patients safe. It is a partnership. Missouri is the only state without a statewide PDMP. St. Francois County passed an ordinance to join the St. Louis County voluntary PDMP in 2017. The first report from the PDMP showed St. Francois County as the highest prescribing county in the state. This was a big concern for the Local Board of Health and, we learned from community partners, the citizens of St. Francois County. Health Center administration has presented opioid-related health data for the county at various meeting and kept hearing from partners that clinician outreach education and patient education were top priorities when it came to prescription opioids.  NaRCAD: So, it sounds like it’s been a success so far. What would you say has been the most impactful piece of this intervention? Amber: The greatest success of academic detailing in St. Francois County so far has been the willingness of most physicians to start the conversation about how they can improve prescribing patterns, and care of patients at risk for or experiencing opioid use disorder (OUD). Also, many physicians have started using the PDMP regularly as a result of our academic detailing visits. NaRCAD: That’s excellent news and shows the impact that 1:1 education can have! Over the course of this pilot project these past 4 months, what has the greatest challenge been with implementing a successful academic detailing intervention to improve opioid safety in St. Francois? Amber: The challenge are the providers who do not want to talk with the detailers, or the ones who flat out refuse to change their prescribing patterns. As a nurse, this is frustrating to me because I believe in quality, evidence-based healthcare for all. The refusal to learn, or seek to learn, new information about medications that are prescribed daily is poor patient care and our citizens deserve better than that.  NaRCAD: That does sound frustrating! During our 2-day training, we really emphasis the importance of asking open-ended questions to draw clinicians out. However, there will always be some clinicians who will not engage, no matter how great of a detailer you are. Victoria Adewumi from the original cohort of LOOPR detailers discussed that in a prior blog post. What is something you wish you knew prior to joining the LOOPR Academic Detailing project? Amber: I wish I’d known more about choosing detailers. Recruitment is important. When recruiting detailers, it is more important to make sure to recruit people who have the bandwidth to do the detailing, rather than making sure they have the perfect clinical background. It may be a good idea to create a formalized agreement to ensure they completed their required detailing visits. NaRCAD: You are spot on, Amber. Recruitment is a complex process. Readers can learn more about this later in the summer when we release our new Implementation Guide to help sites like yours select and hire the right candidates. Readers can read other LOOPR blog interviews here, and stay plugged in for more LOOPR site highlights in the next couple of months.  Biography Amber Elliot, BSN, RN Assistant Director St. Francois County Health Center Amber Elliott is the Assistant Director for the St. Francois County Health Center in Park Hills, MO. She received her Associates Degree in Nursing in 2008 from Mineral Area College to become a Registered Nurse. She went on to obtain her Bachelor’s Degree in Nursing in 2011 from Central Methodist University. She has spent most of her nursing career working in acute settings, primarily hemodialysis. Amber started working in public health four years ago in hopes to make her own community a healthier, safer place to live. Amber has been working on opioid-related activities since 2017. She currently resides in Farmington, MO with her husband and two children. Kayland Arrington, MPH, Program Manager at NaRCADTags: HIV/AIDS, Opioid Safety, LOOPR, Training This New Year, NaRCAD has new staff, new partnership sites, and will be addressing critical topics in health. We’ve had a successful 2018, and we’re already working hard to improve patient health through clinician education in 2019.  One of the main topics we provide support on is HIV prevention for high-risk patients. While it is true that rates of HIV are declining in some populations, other groups are still very much at risk for developing HIV. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), half of all black men who have sex with men will contract HIV in their lifetime. These statistics are staggering, and NaRCAD is doing everything we can to help by engaging directly with frontline providers who can communicate best options for prevention directly to their patients. We do this by training academic detailers to meet with clinicians to offer tailored, evidence-based clinician recommendations.  Image Credit: AIDS Coalition of Nova Scotia Image Credit: AIDS Coalition of Nova Scotia In December, we traveled to Las Vegas to facilitate an AD training to increase prescriptions of Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). PrEP is a daily medication prescribed to people with a high risk of developing HIV. The CDC reports that PrEP reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex by more than 90%; it also reduces the risk of contracting HIV from injection drug use by more than 70%. NaRCAD is continuing our work in 2019 to train health educators to talk to frontline clinicians about the benefits of prescribing PrEP to their high-risk patients. Our first training of 2019 is in February at the PrEP Public Health Detailing Institute in San Francisco, hosted by our partners at the San Francisco Department of Public Health.  We’ve also added on 2 new sites to our county-level LOOPR Partnership! We will be traveling to St. Francois County, Missouri and Ware County, Georgia in March. The CDC has identified 220 counties (5% of counties in the nation) that are at highest risk of HIV and/or Hepatitis C as a result of the opioid crisis. St. Francois County, MO is ranked 69 out of those 220 counties. Ware County, GA is located in the southeast corner of the state and doesn’t have as much access to resources as counties more centrally located. NaRCAD is excited to join both of these high-burden counties in their efforts to reduce harm from the opioid crisis.  One element that is a common thread with both HIV and the opioid crisis is the fact that these are both highly stigmatized clinical topics. Along with community stigma, clinicians themselves may be inadvertently biased against patients with substance use disorder and/or those at high risk for developing HIV. As the result of a fear of stigma, it’s also common for patients to refrain from sharing high risk behavior with their providers. To ensure that front line clinicians increase PrEP prescribing and work to treat pain in safer ways, the academic detailers we train this year will also explore ways to address clinician stigma. Along with our county-level support, we’ll also travel to Tennessee, Oregon, and Maryland this year. And as always, we’ll hold our usual Boston home trainings in May, July, and September before our year comes full circle at our 7th Annual International Conference on Academic Detailing in November. No matter how we connect in the year ahead, our entire team is looking forward to supporting you in 2019—let us know how we can help, and stay tuned for more updates here on the DETAILS Blog.  Biography Kayland Arrington, MPH | Program Manager, NaRCAD Kayland earned her Master’s Degree in Public Health from Boston University, with concentrations in Health Policy and Law and Maternal and Child Health. She has experience coordinating suicide prevention and awareness programs. She also has experience in health promotion and education on topics ranging from substance use disorder to sexual violence. Kayland is passionate about improving access to resources, supporting population health programming, and is an advocate for evidence-based medicine. Read More. Exercising Empathy, Planting Seeds: An Interview with the Manchester, NH Academic Detailing Team10/26/2018 Featuring: Carol Furlong, LCMHC, MAC, MBA, Director of Substance Use Disorders, Elliot Hospital Jill MacGregor, APRN, Catholic Medical Center, & Katie Sawyer, LICSW, MLADC, Director, Integrated Treatment of Co-Occurring Disorders, Network4Health/Mental Health Center of Greater Manchester Interview by Isabel Evans, Fellow, NACCHO, in partnership with NaRCAD  Tags: LOOPR, Opioid Safety, Stigma, Substance Use, Training EDITOR'S NOTE: Manchester, New Hampshire, was the third site of four selected for a 2018 pilot program of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), NACCHO (the National Association of County and City Health Officials), and NaRCAD (The National Resource Center for Academic Detailing). This exciting pilot program focused on community-level work with local public health departments to develop customized interventions to reduce opioid overdose and death. Four sites experiencing significant public health problems related to opioids were selected to be trained in academic detailing; those trained health professionals then conducted 1:1 field visits with front line clinicians to impact behavior around prescribing, treatment referrals, and patient care, with Manchester’s team focusing primarily on access to Medication Assisted Treatment [MAT]. As year 1 comes to a close, we’re showcasing successes from the field. Thanks for talking with us about your work in Manchester, New Hampshire. Can you tell us about your team? How were detailers chosen to represent the health department for this pilot project? Carol: Tim Soucy, from the Manchester Department of Health, contacted representatives at each of our organizations and gave a little bit of information about the training. He asked if our organizations had particular people that might be interested, and my supervisor thought of me, since I was in the middle of developing a MAT program for my organization. I jumped at the chance to participate. Jill: My organization received the same email, and as the primary care lead nurse practitioner, I was considered the most appropriate to participate. Katie: The invitation came from the site that received the CDC grant (City Health Department). The invitation was disseminated among a number of local human service/health agencies who are part of a Network of agencies as a result of our 1115 Waiver partnership.  The NaRCAD team came to your site back in March, 2018, helping you get ready to be ‘in the field’ and talk to clinicians about the opioid crisis. Tell us how that went, and how you applied what you learned in training. Carol: I’m a naturally shy person who dislikes being the center of attention, so I was incredibly nervous about the role plays during training. The turned out to be invaluable, since I use the skills I developed through practicing and receiving feedback during every visit. The role plays prepared me so well for meeting with providers, and I go into the conversations feeling confident and comfortable. When they ask questions, I feel that I know how to answer, or where to turn for more information, such as the wonderful handouts available on the NaRCAD website. Jill: For me, learning how to hold a discussion as a detailer was the most important element of the training. I learned how to frame a conversation using open-ended questions, which allows the discussion to progress. Understanding how to simultaneously get a provider’s perspective, while also giving them the information they need, is a critical detailing skill. Katie: We were able to role play, which has proven very helpful out in the field to stay focused, on topic, and empathetic to the position of each clinician that I speak to. The handouts that NaRCAD provided have easy to read information and great graphics, so they have also proved useful for staying on track with the key messages during detailing visits, along with providing supplemental information.  The opioid epidemic has affected many communities in unique ways. How have local clinicians responded to your visits? What do clinicians in Manchester see as major barriers to improving health for their patients struggling with this issue? Carol: Clinicians can be a little skeptical at first, since they’re often expecting that I’m going to try to “sell them” on something. When I focus on listening to their experiences and their concerns, I’m able to gently address those concerns and give resources or suggestions. Even just having a discussion can help clinicians to feel that you’re interested in how they feel, and that you genuinely want to help them – I would describe some clinicians as “dumbstruck” from our conversations, because they’re preparing to do battle with me, but they instead come to see me as a resource, and are more willing to meeting with me. As for challenges, we deal with a fair amount of stigmatization of substance use. It’s a major barrier, and we’ve had to spend a lot of time addressing that in my organization. Another barrier for clinicians is a preconceived notion that providing MAT is an onerous process, and too time-consuming to add into their schedules. And these two barriers really complement each other in a bad way – I often get providers saying that MAT is too much work and that their MAT patients will just end up using opioids again and ending up back in the emergency room. Breaking down these misconceptions about MAT and getting to the root of the stigma against MAT is a big challenge. However, we’re approaching these challenges with education and lots of conversations, since we’ve found that helping our staff to get a better sense of addiction as a disease is really invaluable to making them more open to MAT and treating people with opioid use disorder. The timing of the academic detailing initiative couldn’t have been better for my organization, because having conversations about addiction leads well into having conversations about MAT, and vice versa. Engaging in academic detailing has opened up a whole new avenue of clinician education for me. Jill: Because of my role at my health system, I talk to providers about many different topics and they’re used to me approaching them, which has definitely helped give me and automatic “in” and bring up sensitive topics. My institutional knowledge helps too, since I can answer questions specific to my organization and our various programs or resources around opioids.  A major challenge I face is that providers don’t think they have the time and resources to implement MAT into primary care, and they don’t feel they have the behavioral health support to do so successfully. However, I’ve found that this is often based around a lack of knowledge, since when I ask more probing questions about MAT, it’s often clear that they don’t really know much about it! Providers will come to conclusions without getting the right education, and I find that they often “change their tune” when I give them more information. Providers are also hesitant about writing a prescription for a MAT patient if there isn’t someone in their office who can talk to the patient about addiction itself. Right now, we’re working on integrating behavioral health clinicians into primary care, which I’m hopeful will help with this very real concern. Katie: There has been some hesitation in sharing with detailers, in regards to professional experience, as I believe most clinicians are on edge in trying to do the best that they can to address patient needs, while also supporting alternatives to typical or historical use of prescribed opioids. With an empathetic and interested stance, I’ve found that most clinicians are open with their experience and struggles. There are a number of themes among clinicians for challenges that I’ve noticed, including a limited behavioral health workforce to support what they view as an ideal MAT protocol, which would include individual and group counseling, regular urine toxicology screens, and wraparound services along the continuum of care. In addition, there is a concern among providers about the potential diversion of Buprenorphine by patients.

Katie: It has been rewarding to meet with each clinician for different reasons – I would view success as learning more about the clinicians that are already on board and excited to pursue getting a waiver, as it gets them talking and feeling a renewed energy to share with others. I view my conversations with clinicians who are not interested in pursuing a waiver as equally rewarding, since it allows for both of us to share and hear the other’s perspective. We can agree that the work is needed and challenging, no matter how we decide to go about addressing the needs of our patients. Lastly, what advice would you tell new detailers? What do you wish you knew when you started out? Carol: I would tell new detailers to take a deep breath and know that you’re ready for this – NaRCAD does such a good job of training us as detailers, and you just feel ready. Jill: I would say to recognize that everyone has a natural process for adapting to new ideas. You’ll get some providers who are ready and energized, some who will want to watch others in action before they jump in, and some who simply may not be interested. It can be frustrating when providers aren’t interested in your topic or resources, but understand that this is natural, and don’t take it personally! Every visit will be different, and that’s okay. Katie: My advice is to remember that success is not defined as “convincing” someone that the topic of your detailing visit is “the right answer”. In fact, trying to convince another person of anything is essentially walking against waves. Instead, be open to listening to that person and their experiences, and then value the experience that they have had. This is more likely to open the conversation to allow you to share your wealth of information and experiences. It’s all about planting seeds. Ideas? Comments? Questions? Sound off on this blog in the comments section below!

Opening Up the Conversation: An Interview with the Bell County, Kentucky Academic Detailing Program10/26/2018  Featuring: Robin Tuttle, RN, ER Nurse, Academic Detailer, NaRCAD Training Alumnus Interview by Kabaye Diriba, Senior Program Analyst, NACCHO, in partnership with NaRCAD Tags: Detailing Visits, LOOPR, Opioid Safety, Rural AD Programs EDITOR'S NOTE: Bell County, Kentucky, was the first site of four selected for a 2018 pilot program of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), NACCHO (the National Association of City and County Health Officials), and NaRCAD (The National Resource Center for Academic Detailing). This exciting pilot program focused on community-level work with local public health departments to develop customized interventions to reduce opioid overdose and death. Four sites experiencing significant public health problems related to opioids were selected to be trained in academic detailing; those trained health professionals then conducted 1:1 field visits with front line clinicians to impact behavior around prescribing, treatment referrals, and patient care, all within a rural area. As year 1 comes to a close, we’re showcasing successes from the field. Thanks for talking with us about your on this pilot project with NACCHO, the CDC, and NaRCAD, working to support local efforts in your community. Robin: What we’ve been doing has been a breath of fresh air! I'm proud to be a part of it, and happy to help in any way that I can. Tell us how local detailers were selected for this project—what kinds of professional backgrounds make up your diverse team members? Robin: I was asked by a co-worker, another detailer, who thought “I know this really outgoing, outspoken person that might fit the team.” Our team is made up of people that have hands-on knowledge about the opioid epidemic. I’ve been in healthcare since 1988 and I’ve been living here in Bell County for 30 years. I started working as a nurse aid at one of the local hospitals and then went on to college to get my RN. Our detailing team all had a common interest when we got together.  What elements of the training do you apply most often during your visits when delivering your key messages? Robin: What helped me the most was that last day of training when we were practicing academic detailing. Asking open-ended questions is the most important thing. You get so wrapped up in wanting to deliver your messages, but it’s not necessary that you get all of your messages in on that first visit. You may feel rushed to deliver all your messages if you’re afraid you’re not going to make it back in the door, but what I found is the more I met with doctors, and the more I said things like, “What have you seen in your practice?” or “Tell me about a patient…” or “Talk to me about the problems you’re having…”, the more I saw the conversation open up. That’s something I really picked up on the second day of training—learning to turn it back around and asking [needs assessment] questions. Let them get involved, and let me really listen to what they have to say; that way it'll help contribute to the conversation going forward. The opioid epidemic can be a sensitive topic. When you approach clinicians to discuss their behaviors around the opioid epidemic, how are you generally received? What do clinicians in Bell County see as major challenges in your community? Robin: Almost everyone I spoke to was very receptive about everything that we talked about, including all 5 of our campaign’s key messages. Because treatment in this area is slim to none, it all circled back to, “What if I find someone [a patient] that has opioid use disorder? How can you help me?” Doctors here are telling me that even people that have overdosed and come to the hospital are having a hard time [getting access to treatment]. There are places that are not in Bell County, but we would need some sort of transportation system that could get patients to those places.  What challenges do Bell County clinicians face, along with being busy, when trying to support their patients who are prescribed opioids? Robin: Clinicians are often challenged in identifying symptoms of someone with opioid use disorder. Also, sometimes patients are sent to a pain [management] clinic, but those don’t always work. In our community, we can send them to the local Suboxone clinic which is accessible and easy to get to. When it comes to Suboxone, you cannot look at it as an “all-or-nothing” approach. That’s a challenge here in Bell County, trying to get the community to know that abstinence is not always the answer, and sometimes people might have to take some form of medication for life to get the wiring back together that they've already lost because of their disorder. I also understand some of the doctors are adamant about their current patients that have been taking these medications for 25 years for this chronic pain, which they don’t think they can do much about, and they’re concerned about this newer generation [of patients] coming in.  What have been some of the more rewarding exchanges you’ve had with clinicians you’ve met with? Robin: I've had a lot of good visits, but this one sticks out in my mind: there was one clinician where I felt immediately like I was going to get the “brush off”. But I ended up staying for an hour and a half! I sat there with this doctor, who I’ve had a challenging professional relationship with historically, and he ended up talking to me at length about patients he was seeing, and those he had inherited. I was so excited that I’d spoken with him for so long, and that I’d covered all 5 of our campaign’s key messages. I walked away from that visit with questions to follow up on that I wanted to be able to answer for him at a future visit, and I felt like I made a new friend. What do you want to tell new detailers who are just starting to form teams and try this kind of 1:1 outreach education model out with clinicians in their communities? What piece of advice would you have appreciated when you started your first detailing visits? Robin: Try not to get discouraged! After we divided up all the physicians, we started making phone calls. That can be discouraging. I found out we actually had more luck stopping by. We called it the “drug representative look”: you dress up, put your badge on that says academic detailer, have the clipboard and all the paperwork, and you look professional. I really found out that I had more luck by just walking in and saying, “Do you have a minute?” Don’t get discouraged if you're making calls all day long and they keep putting you off, because receptionists are making appointments all day long too and it’s hard to explain what you’re doing over the telephone. We definitely felt discouraged during the first couple of weeks of outreach. We were feeling like we hit a brick wall, and that’s when we coined the term "drive-by” detailing visits. We started driving around and just showing up at offices. So, get out and drive if you can’t get through over the phone. Go with a card and introduce yourself. They [clinicians] all want to talk about opioids. You'll be surprised when you get in the room with them and they start talking. Ideas? Comments? Questions? Sound off on this blog in the comments section below!

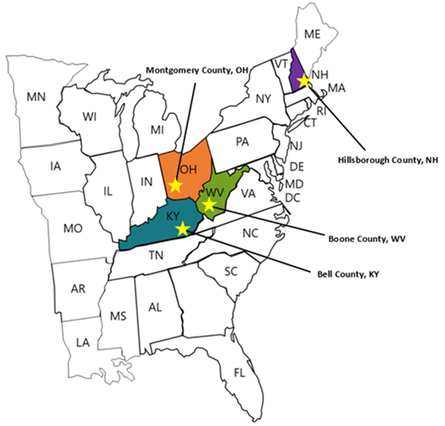

Director’s Letter: Mike Fischer, MD, MS  Tags: Director's Letter, LOOPR, Opioid Safety, Rural AD Programs, Training The opioid crisis has been recognized as a major national public health problem, but it actually reflects a collection of many thousands of local crises playing out in individual cities and counties. Each region faces a distinctive set of challenges, driven by economic and social factors, local medical practice patterns, political environment and pressures, and many other considerations. Identifying and implementing effective solutions to address the opioid crisis requires developing an understanding of how these individual challenges interact, and what strategies are most effective in specific situations--one of which is academic detailing.  The NaRCAD team is partnering with the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and NACCHO (the National Association of City and County Health Officials) on an exciting pilot program working with local health officials to develop customized interventions to reduce opioid overdose and death. Four sites experiencing significant public health problems related to opioids were selected: Boone County, Kentucky; Bell County, West Virginia; Manchester, New Hampshire; and Dayton, Ohio.  Public health officials at each site identified a wide range of local stakeholders to participate in developing a community action plan and recruited trainees to complete NaRCAD’s academic detailing training course, which we customized to address the unique challenges that each community faces. We also developed a specialized online toolkit for these sites, including discussion boards, local resources, and printable resources.  A trainee from Bell County, Kentucky, delivers a key message. A trainee from Bell County, Kentucky, delivers a key message. We traveled to each site in March and April of this year, facilitating hands-on trainings in the techniques of academic detailing in alignment with the CDC prescribing guidelines. Trainees came from diverse backgrounds, including pharmacists, nurses, public health officials, and students in the health professions, including pharmacy students, dental students, and medical school students. Plans for implementing AD varied by site depending on the local health care environment; some sites focused more heavily on appropriate prescribing of opioids by clinicians, while others prioritized increasing referral rates for patients with opioid use disorder (OUD), including access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT).  Practicing a concise introduction in Manchester, New Hampshire. Practicing a concise introduction in Manchester, New Hampshire. As the AD trainees at each pilot site continue their work in the field, we’ll learn more about how these diverse strategies succeed, and how we can support adaptations to make academic detailing more impactful. This important collaboration has allowed us to form invaluable partnerships with CDC and NACCHO, leveraging national resources to improve local responses to this epidemic through plans that respond more precisely to local needs and priorities. We’re excited for this pilot program to serve as a model for future opioid safety AD interventions, and we’ll be providing updates here on the blog. In the meantime, tell us: what's happening in your local community around the opioid crisis? Sound off in the comments section below, and let us know if you think clinician-facing education could be a strategy that would improve outcomes for your community. And join us for our next training and our terrific annual conference to learn more about this and other exciting AD projects. -Mike  Biography. Michael Fischer, MD, MS | Director of NaRCAD Dr. Fischer is a general internist, pharmacoepidemiologist, and health services researcher. He is an Associate Professor of Medicine at Harvard and a clinically active primary care physician and educator at Brigham & Women’s Hospital. With extensive experience in designing and evaluating interventions to improve medication use, he has published numerous studies demonstrating potential gains from improved prescribing. Read more.  Tags: Detailing Visits, HIV/AIDS, LOOPR, Opioid Safety, Training We've been staying busy here at NaRCAD this spring! With public health challenges like the opioid crisis, and the continued need for HIV prevention, the team here at NaRCAD has been on the road for 5 trainings in 6 weeks, and we're not stopping yet! On February 14th - 16th, 2018, NaRCAD joined the amazing teams at San Francisco Department of Public Health and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene for an exciting initiative: A Public Health Detailing Institute on HIV PrEP and RAPID. Hosted in San Francisco's South Market neighborhood, 31 trainees attended, representing diverse public health departments from Texas, Connecticut, Alaska, Louisiana, Florida, Tennessee, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Mississippi, Michigan, Oregon, Nevada, Virginia, and beyond. These trainees joined the institute for a customized, 3-day event focusing on learning the techniques of academic detailing, along with showcasing best practices and success stories via special presentations and expert panels.  This past month, from March 7th through April 4th, 2018, NaRCAD hit the road four more times, as part of an exciting 4-site pilot project in partnership with our terrific colleagues at the CDC (Center for Disease Control) and NACCHO (The National Association of County and City Health Officials). Upon identifying counties and cities with the highest burden of fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose and high prescribing rates, the CDC selected Bell County, Kentucky; Boone County, West Virginia; Manchester, New Hampshire; and Dayton, Ohio as 4 pilot sites in which to convene with key community stakeholders and roll out community action plans, along with targeted academic detailing interventions.  Our work has involved launching on-location trainings at each of these pilot sites, focusing on providing front line clinicians with tools and support to improve outcomes for patients. Messaging and support for these campaigns include lowering prescribing rates, referring patients to treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) including Medication Assisted Training (MAT), and using their state's PDMP (Prescription Drug Monitoring Program) to identify troubling patterns of use, which may, in turn, help to identify those patients who need more support and care.  Trainees at each site of these pilot sites work with us across two days to learn the structure of an academic detailing visit, practice role playing 1:1 visits with clinicians, and become experts at using educational materials (including a suite of materials constructed by the CDC based on their 2016 Opioid Prescribing Guidelines). Our pilot site trainees walk away from our trainings ready to actively engage with clinicians to assess individual needs and provide customized support, and encourage behavior change for the opioid crisis in their respective communities.  NaRCAD's team will continue to focus on launching new academic detailing interventions across the U.S. well into 2018, with upcoming opioid-specific trainings being carried out in late May in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with the University of New Mexico's Health Sciences Center, and in late June in Lansing, Michigan, with the Michigan Public Health Institute.  Our next all-topic, AD techniques training in Boston will kick off at the end of this month, where we'll train 24 health professionals from across the U.S.--we'll report back after that training and share lessons learned, highlights, slide decks, and clinical topics from represented programs, and we look forward to sharing those with our community. Join our subscription list to receive alerts for upcoming training opportunities. Want to customize a clinical topic-specific training for 15 trainees or more, on site in your community? Reach out to us to schedule a training consultation call at [email protected]. We can't wait to work with you! -The NaRCAD Team This press release originally appeared on publicnow.com and was written by UCSOP. Tags: LOOPR, Opioid Safety, Rural AD Programs, Substance Use, Training The University of Charleston School of Pharmacy (UCSOP) is partnering with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to pilot the National Resource Center for Academic Detailing (NaRCAD) program at the Boone County Health Department in Southern West Virginia. Academic detailing is a one-on-one outreach education technique which allows pharmacists, pharmacy students and other health care professionals to educate prescribers on the dangers of overprescribing opioids and also recognize the signs of opioid abuse.  UCSOP participants include student pharmacists Angela Withrow (class of 2019), Amy Bateman (class of 2018), Joshua McIntyre (class of 2021), Jami Swift (class of 2021), and assistant professor Dr. Sarah Embrey. These individuals make up five of the seven selected persons being trained for the program. A two-day training will kick-off the program on March 14-15, 2018. 'Participation in this important pilot project is just one more way UCSOP students and faculty work to educate and serve communities throughout West Virginia on opioid use/abuse by sharing best prescribing practices, delivering prevention education, and encouraging recovery and treatment,' said Dr. Susan Gardner Bissett, Assistant Dean for Professional and Student Affairs.  NaRCAD was founded in 2010 and is a national resource center that supports clinical outreach education programs across the United States. The goal through its trainings and program support is for clinical educators to have a greater impact when visiting clinicians and aiding those clinicians on making evidence-based decisions. Interventions supported include reducing opioid abuse, HIV/STI screening and prevention, prenatal health, smoking cessation, chronic disease management, and more. For more information, visit https://www.narcad.org/. |

Highlighting Best PracticesWe highlight what's working in clinical education through interviews, features, event recaps, and guest blogs, offering clinical educators the chance to share successes and lessons learned from around the country & beyond. Search Archives

|