|

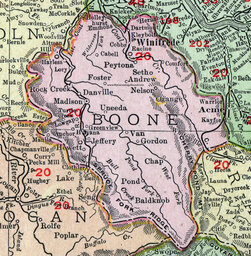

OVERVIEW: Boone County, West Virginia was one of 4 original site selected for years 1 + 2 of a pilot program of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), NACCHO (the National Association of County and City Health Officials), and our team at NaRCAD (The National Resource Center for Academic Detailing). This exciting pilot program focused on community-level work with local public health departments to develop customized interventions to reduce opioid overdose and death. Six sites experiencing significant public health problems related to opioids were selected over the two years to be trained in academic detailing; those trained health professionals then conducted 1:1 field visits with front line clinicians to impact behavior around prescribing, treatment referrals, and patient care, all within a rural area. As year 2 comes to a close, we’re showcasing stories from the field. Tags: Detailing Visits, LOOPR, Opioid Safety, Program Management, Rural AD Programs  Via NaRCAD, NACCHO, & the CDC’s pilot project, “LOOPR”, we were able to connect with high-burden counties across the U.S. whose rates of high prescribing and high fatal and non-fatal overdoses identified them as a county in need of support. NaRCAD worked on the implementation of an academic detailing initiative over the course of 2017-2019 with Boone County, located in rural West Virginia. Boone County ranks as the 22nd most vulnerable county across all counties in the United States, with the highest drug overdose mortality rate of all counties in West Virginia. Due to these and other data, Boone was identified as a key county in which to test the implementation of an academic detailing program, in which trained detailers would speak to clinicians and pharmacists about safer prescribing of opioids, checking the state’s prescription drug monitoring program to avoid dangerous co-prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines, and to try and provide treatment, non-opioid therapy, and resources to patients in need.  One of the most unique approaches across all 5 sites of the LOOPR Project was carried out in Boone, with the team of 5 detailers being hand-selected from the nearby University of Charleston West Virginia’s School of Pharmacy. Four of these five recruited detailers were students in training to become pharmacists; one detailer works at the university as a professor of pharmacy. Selecting pharmacy students and faculty allowed for many positive approaches to the project, as well as creating unforeseen challenges. Programs considering hiring student detailers can often rely on the flexibility of students’ schedules, as well as an enthusiasm and energy for learning that may exist in smaller quantities later in one’s career, when full-time roles in healthcare take priority. While many career-established clinicians may have little room in their schedules to squeeze in 1:1 sessions with fellow clinicians, students may have more of an ability to shift their schedules, especially if they are not yet carrying out residency.  a reflections from Boone County’s Detailing Team, it’s clear that best practices in detailing should also consider the vast amounts of new information that students are absorbing early in their learning careers, and that learning clinical content may take longer to grasp. In addition, the comfort level with new clinical information may lead to less confidence in discussing best practices, especially with clinicians whose careers are much more established. Finding the right balance of tenacity, communications savvy, more time to ramp up to comfort in delivering and leading 1:1 sessions, an additional amount of technical assistance provided at more frequent intervals, and additional practice time or shadowing time with a mentor, can all benefit student detailers who are training to join a clinical outreach education team in a high burden area. With these elements in place, a student detailer may be poised for success—however, other considerations include the fact that students may have new projects, graduation pending, or life events which may end up limiting their ability to dedicate consistent time to a project rolled out over many months.  Other reflections from the Boone County AD Team included looking carefully at the social climate in which AD interventions of this nature may be implemented. While no county is free of potential clinician-level or community-level stigma, particularly around issues such as opioid use disorder, Boone’s AD team shared a particularly challenging setting within which the local community was not as supportive of evidence-based harm reduction initiatives as would be beneficial. One detailer’s suggestion to raise the visibility of and advocacy for harm reduction included considering a public health campaign prior to a detailing campaign, to ensure that subsequent roll-out of detailing is more sustainable and met with an openness from clinicians to consider behavior change. NaRCAD’s work with the public health department in Boone County, in partnership with the students and faculty of University of Charleston, West Virginia, provided the kinds of insights critical to learning from a pilot project of this nature. As with many pilot studies, any information gathered can illustrate a clearer picture of the landscape within which public health initiatives can be implemented, so that future projects may have a greater impact. With many thanks to the student and faculty team of Boone County’s Academic Detailing Project team, we and our partners are grateful to have learned so much over the past two years. Comments are closed.

|

Highlighting Best PracticesWe highlight what's working in clinical education through interviews, features, event recaps, and guest blogs, offering clinical educators the chance to share successes and lessons learned from around the country & beyond. Search Archives

|